61 6.3 Classifying Human Variation

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Figure 6.3.1 How would you classify these people?

Why Classify?

What do you see when you look at Figure 6.3.1? Did you sort individuals into categories based in gender, age, body type, facial features, skin colour or other characteristics? As humans, we seem to have a penchant for classifying and labeling people and things. It helps us establish a sense of order in the world around us. The 18th century taxonomist Carl Linnaeus, for example, classified virtually all known living things into different species, genera, families, and other taxonomic categories. His classifications were based on observable phenotypic characteristics, such as skin colour. Modern biological classifications of living things are usually based on phylogenetic relationships. Phylogenies reflect evolutionary history and group together living things that are related by descent from a common ancestor.

Starting with Linnaeus and continuing to the present, scientists and others have attempted to classify human variation. There are three basic approaches to classification: typological, populational, and clinal.

Typological Approach

The typological approach involves creating a typology, which is a system of discrete types, or categories. This approach was widely used by scientists up through the early 20th century. Racial classifications are typological classifications. They place people into a small number of discrete categories, or races, based on a few readily observable traits, such as skin colour, hair texture, facial features, and body build.

Racial Classifications and Racism

Racial classifications of humans probably go back as long as people distinguished “us” from “them.” An early “scientific” classification of humans into races is Linnaeus’ 1735 classification. He divided Homo sapiens into continental races, which he named europaeus, asiaticus, americanus, and afer. Linnaeus described these races in terms of observable physical traits. He also associated, inaccurately, each race with different personality qualities and behaviors. For example, he described Homo sapiens europaeus as active and adventurous and Homo sapiens afer as lazy and careless. In 1795, the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach proposed five major races of Homo sapiens, which he named the caucasoid, mongoloid, negroid, American Indian, and Malayan races. Blumenbach thought that the caucasoid race was the original race, and that the other races arose in a process of “degeneration” from the caucasoids.

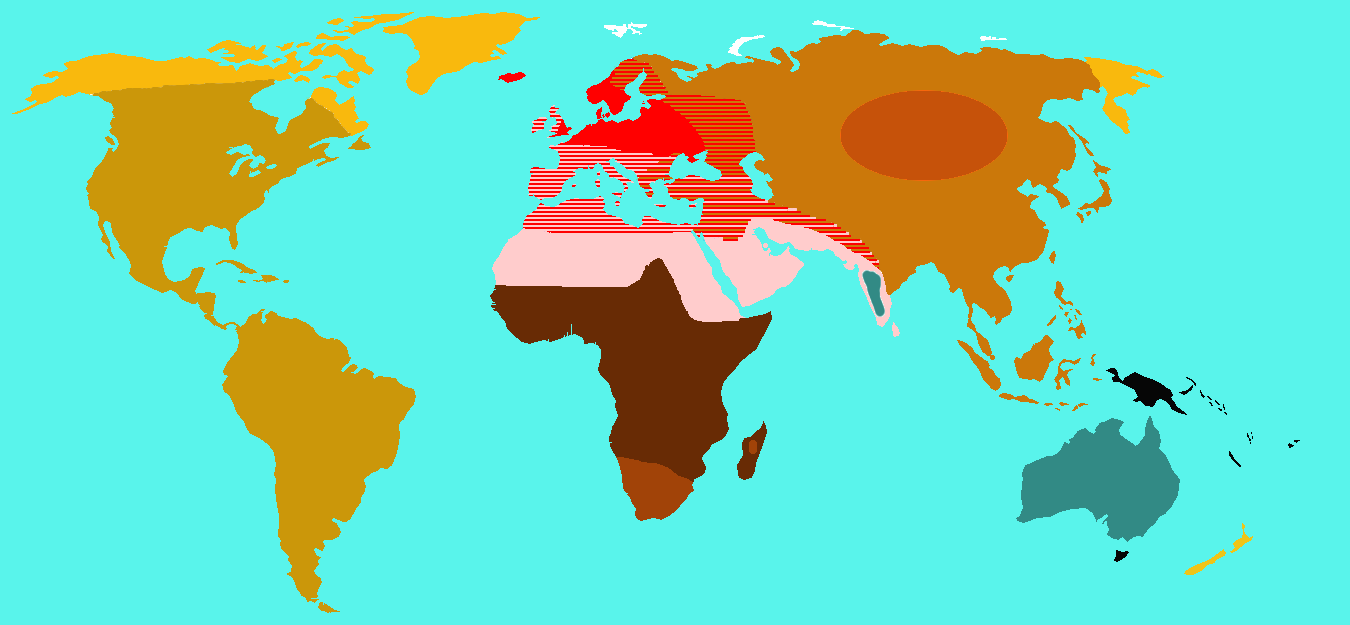

In 1870, the English biologist Thomas Huxley classified Homo sapiens into nine races which were distributed geographically. The map in Figure 6.3.2 shows how Huxley thought the races were distributed worldwide. Each colour represents one of Huxley’s proposed races. These categories included “Australoid,” “Xanthochroi,” “Melanochori,” “Negroes,” and “Mongoloids,” and they are not used today. It should be noted that Huxley did not hold such strong negative stereotypes about non-European (or non-caucasoid) races as did his intellectual forebears. Huxley, however, still attributed different behaviors to racial groups that had nothing to do with the colour of their skin or continent of origin.

By the early 20th century, so-called scientific racism was a popular ideology. This was the idea that race is a biological concept and that human behavior is partly determined by race. At around 1950, in a series of groundbreaking studies of skeletal anatomy, anthropologist Franz Boas showed that cranial (skull) shape and size were highly malleable, depending on environmental factors (such as health and nutrition). He contrasted this with racial anthropologists’ claims that head shape is a stable racial trait. In this way, Boas demonstrated that this commonly used racial trait was determined by the environment, and not just genes. Boas also worked to demonstrate that differences in human behavior are not determined primarily by innate biological dispositions, but are largely the result of cultural differences acquired through social learning.

Unfortunately, racism still persists today — in society at large, if not in science. This is the association of racial traits (such as skin colour) with unrelated traits (such as intelligence), often leading to prejudice and discrimination against people based only on how they look. The concept of human race is real, not in a biological sense, but in a social sense. Racial stereotypes and racism are deeply ingrained in our history and culture, and they have real material effects on human lives.

Additional Problems with Typological Classification

Besides the problem of racism, there are other problems with typological approaches to the biological classification of Homo sapiens. One problem is that most human biological traits are not either present or absent, but instead vary on a continuum. This type of distribution cannot be adequately represented by discrete categories, such as races. The typological approach also results in groupings of people that may be similar in terms of some traits, but not others. How people are grouped together depends on which traits are chosen. In addition, the number of groups that are needed to classify people depends on the number of traits that are used. The greater the number of traits, the greater the number of racial categories there must be. If racial categories depend on the traits chosen to define them, it is clear that the racial classifications are arbitrary and do not reflect biological reality.

Another problem with typological classifications is that they lead to the mistaken belief that people within typological categories are more similar to each other than they are to people in other categories. There is actually more variation within than between typological groups. An estimated 90 per cent of human genetic variation occurs between people within races, and only 10 per cent occurs between races. Clearly, races are far from homogenous in terms of their genetic composition. In short, we are all more alike than we are different.

Populational Approach

By the middle of the 20th century, scientists started advocating a populational approach to classifying Homo sapiens. This approach is based on the idea that the breeding population is the only biologically meaningful group. The breeding population is the unit of evolution, and it includes people who have mated and produced offspring together for many generations. As a result, members of the same breeding population should share many genetic traits. You would also expect them to have many of the same phenotypic traits, because of their similar genetic makeup.

While the populational approach makes sense in theory, in reality, it can rarely be applied, because most human populations are not closed breeding populations. Some people have always selected mates from outside their local population (even mating with archaic humans such as Neanderthals). This tendency has increased dramatically in recent centuries with the advent of efficient means of traveling long distances. As a consequence, there are very few remaining distinct breeding populations within the human species.

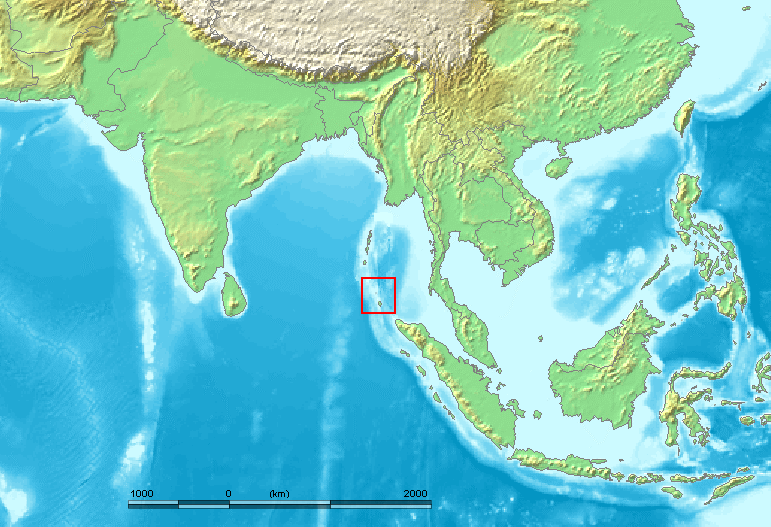

An example of one such population is the Sentinelese, a small population of hunter-gatherers who live alone on a small island in the Andaman Islands (see the map). The Sentinelese are thought to be direct descendants of the first modern humans to leave Africa, and they may have lived in the Andaman Islands for as long as 60 thousand years. The Sentinelese are also one of the most isolated human populations on Earth. The fact that their language is distinctly different from other Andaman Islands languages is evidence that they have had little contact with other people for thousands of years. Although closed breeding populations (such as the Sentinelese) may be useful for investigating questions about evolutionary processes, they are not useful for classifying most of humanity.

Clinal Approach

By the 1960s, scientists began to use a clinal approach to classify human variation. This approach maps variation in traits over geographic regions (such as continents) or even worldwide. Clinal models are a useful way of describing human variation that does not lead to discrete races or other categories of people.

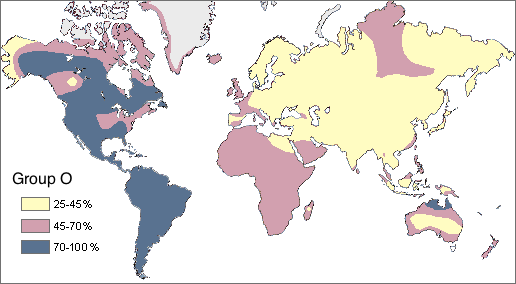

In Figure 6.3.4 you can see a worldwide clinal map for type O blood in the human ABO blood group system. The frequency of this trait is shown for the indigenous populations of various regions. It is lowest throughout Asia and highest in Native American populations in both North and South America. This geographic distribution results from the complex interaction of a variety of factors, including natural selection, genetic drift, and gene flow. You can read more about geographic variation in blood types in the concept Variation in Blood Types.

Clinal maps for many genetic traits show variation that changes gradually from one geographic area to another, which may happen because of the nature of gene flow. Gene flow occurs when mating takes place between people in different populations. The likelihood of mating with others depends on their distance from us. You may not marry the boy or girl next door, but your mate is more likely to be someone in the same state or country than someone on another continent.

Natural selection has a major impact on the clinal distribution of some traits, because variation in the traits tracks variation in selective pressures. For example, the environmental stressor of malaria varies throughout Africa with climate, as you can see in the left-hand map below (Figure 6.3.5). The sickle cell trait that protects from malaria has a similar distribution, as shown in the right-hand map.

Figure 6.3.5

6.3 Summary

- Humans seem to have a need to classify and label people based on their similarities and differences. Three approaches to classifying human variation include typological, populational, and clinal approaches.

- The typological approach involves creating a typology, which is a system of discrete categories, or races. This approach was widely used by scientists until the early 20th century. Racial categories are based on observable phenotypic traits (such as skin colour), but other traits and behaviors are often assumed to apply to racial groups, as well. The use of racial classifications often leads to racism.

- By the mid-20th century, scientists started advocating a population approach. This assumes that the breeding population, which is the unit of evolution, is the only biologically meaningful group. While this approach makes sense in theory, in reality, it can rarely be applied to actual human populations. With few exceptions, most human populations are not closed breeding populations.

- By the 1960s, scientists began to use a clinal approach to classify human variation. This approach maps variation in the frequency of traits or alleles over geographic regions or worldwide. Clinal maps for many genetic traits show variation that changes gradually from one geographic area to another. This type of distribution may result from gene flow and/or natural selection.

6.3 Review Questions

- Name the 18th century taxonomist that classified virtually all known living things.

- Describe the typological approach to classifying human variation.

- Discuss why typological classifications of Homo sapiens are associated with racism.

- Why is the breeding population considered to be the most meaningful biological group?

- Explain why it is generally unrealistic to apply a populational approach to classifying the human species.

- What does a clinal map show?

- Explain how gene flow and natural selection can result in a gradual change in the frequency of a trait over geographic space.

- Most human traits vary on a continuum. Explain why this presents a problem for the typological classification approach.

-

6.3 Explore More

The Biology of Race in the Absence of Biological Races,

Centre for Genetic Medicine, 2015.

Nina Jablonski breaks the illusion of skin color, TED, 2009.

The science of skin color – Angela Koine Flynn, TED-Ed, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 6.3.1

- Three women sitting by flowers and laughing by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Two women sitting on sofa by AllGo on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Young people in conversation by Alexis Brown on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Men talking in the cold by Anna Vander Stel on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Laughing by the tracks by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 6.3.2

Huxley_races by Wobble on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.3.3

Nicobar_Islands is edited by M.Minderhoud on Wikimedia Commons, and was released into the public domain by its original author, www.demis.nl. (See also approval email on de.wp and its clarification.)

Figure 6.3.4

Map_of_Group_O/ (Percent of Native population that has the O blood type) by Ephert on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en) license. (Original Spanish edition by Maulucioni)

Figure 6.3.5

- Malaria distribution by Muntuwandi at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) license.

- Sickle cell distribution by Muntuwandi at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) license.

References

Centre for Genetic Medicine. (2015, July 14). The biology of race in the absence of biological races. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ntimKsWDUpA&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2009, August 7). Nina Jablonski breaks the illusion of skin color. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOSPNVunyFQ&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2016, February 16). The science of skin color – Angela Koine Flynn. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_r4c2NT4naQ&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 27). Carl Linnaeus. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Carl_Linnaeus&oldid=964690855

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, May 18). Franz Boas. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Franz_Boas&oldid=957282443

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 5). Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Johann_Friedrich_Blumenbach&oldid=966196943

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 11). Sentinelese. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Sentinelese&oldid=967121254

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 14). Thomas Henry Huxley. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thomas_Henry_Huxley&oldid=967701553

A classification according to general type, especially in archaeology, psychology, or the social sciences.

A falsely held, pseudoscientific belief, sometimes termed biological racism, that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination).

The prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against someone of a different race based on the belief that one's own race is superior.

A population within which free interbreeding takes place and evolutionary change may appear and be preserved.

To arrange a group of living things into classes or categories according to shared qualities or characteristics.