117 13.2 Structure and Function of the Respiratory System

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Seeing Your Breath

Why can you “see your breath” on a cold day? The air you exhale through your nose and mouth is warm like the inside of your body. Exhaled air also contains a lot of water vapor, because it passes over moist surfaces from the lungs to the nose or mouth. The water vapor in your breath cools suddenly when it reaches the much colder outside air. This causes the water vapor to condense into a fog of tiny droplets of liquid water. You release water vapor and other gases from your body through the process of respiration.

What is Respiration?

Respiration is the life-sustaining process in which gases are exchanged between the body and the outside atmosphere. Specifically, oxygen moves from the outside air into the body; and water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other waste gases move from inside the body to the outside air. Respiration is carried out mainly by the respiratory system. It is important to note that respiration by the respiratory system is not the same process as cellular respiration —which occurs inside cells — although the two processes are closely connected. Cellular respiration is the metabolic process in which cells obtain energy, usually by “burning” glucose in the presence of oxygen. When cellular respiration is aerobic, it uses oxygen and releases carbon dioxide as a waste product. Respiration by the respiratory system supplies the oxygen needed by cells for aerobic cellular respiration, and removes the carbon dioxide produced by cells during cellular respiration.

Respiration by the respiratory system actually involves two subsidiary processes. One process is ventilation, or breathing. Ventilation is the physical process of conducting air to and from the lungs. The other process is gas exchange. This is the biochemical process in which oxygen diffuses out of the air and into the blood, while carbon dioxide and other waste gases diffuse out of the blood and into the air. All of the organs of the respiratory system are involved in breathing, but only the lungs are involved in gas exchange.

Respiratory Organs

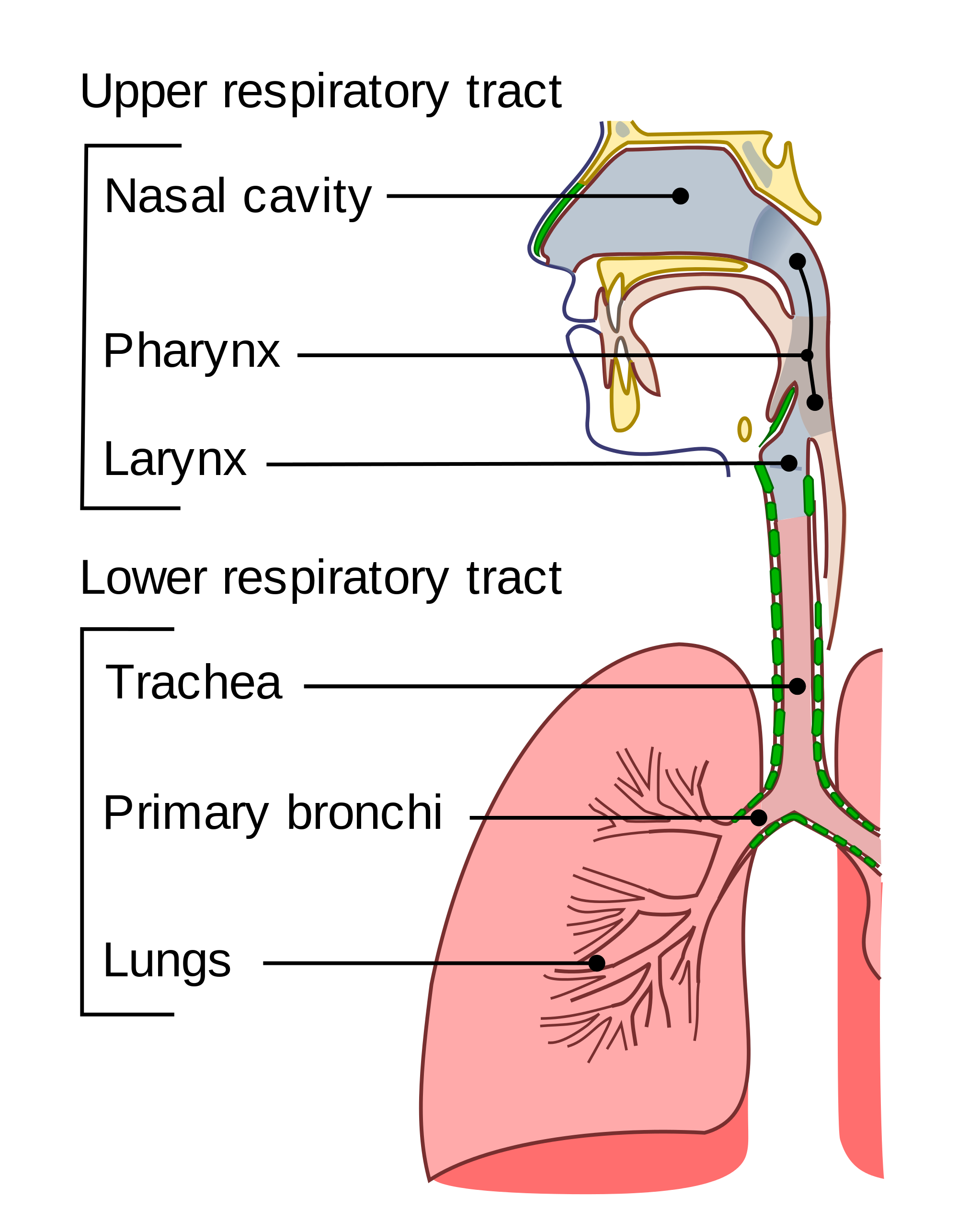

The organs of the respiratory system form a continuous system of passages, called the respiratory tract, through which air flows into and out of the body. The respiratory tract has two major divisions: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract. The organs in each division are shown in Figure 13.2.2. In addition to these organs, certain muscles of the thorax (body cavity that fills the chest) are also involved in respiration by enabling breathing. Most important is a large muscle called the diaphragm, which lies below the lungs and separates the thorax from the abdomen. Smaller muscles between the ribs also play a role in breathing.

Upper Respiratory Tract

All of the organs and other structures of the upper respiratory tract are involved in conduction, or the movement of air into and out of the body. Upper respiratory tract organs provide a route for air to move between the outside atmosphere and the lungs. They also clean, humidify, and warm the incoming air. No gas exchange occurs in these organs.

Nasal Cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space in the skull above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. It is a continuation of the two nostrils. As inhaled air flows through the nasal cavity, it is warmed and humidified by blood vessels very close to the surface of this epithelial tissue . Hairs in the nose and mucous produced by mucous membranes help trap larger foreign particles in the air before they go deeper into the respiratory tract. In addition to its respiratory functions, the nasal cavity also contains chemoreceptors needed for sense of smell, and contribution to the sense of taste.

Pharynx

The pharynx is a tube-like structure that connects the nasal cavity and the back of the mouth to other structures lower in the throat, including the larynx. The pharynx has dual functions — both air and food (or other swallowed substances) pass through it, so it is part of both the respiratory and the digestive systems. Air passes from the nasal cavity through the pharynx to the larynx (as well as in the opposite direction). Food passes from the mouth through the pharynx to the esophagus.

Larynx

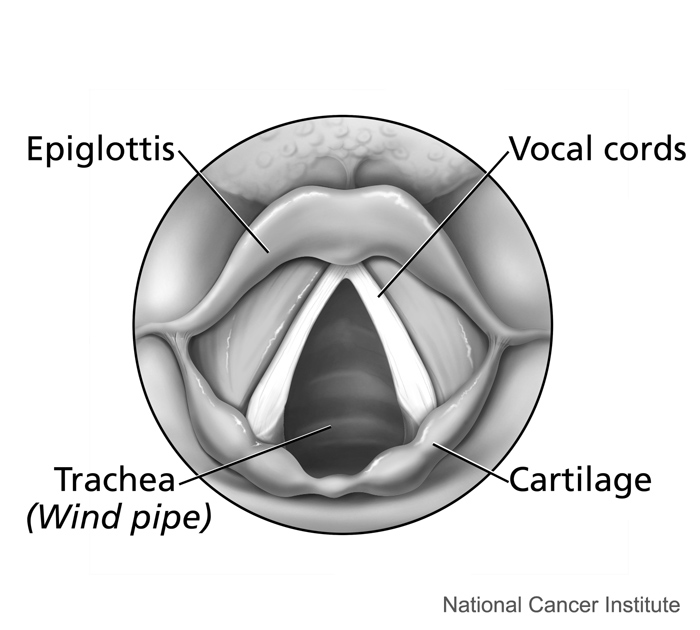

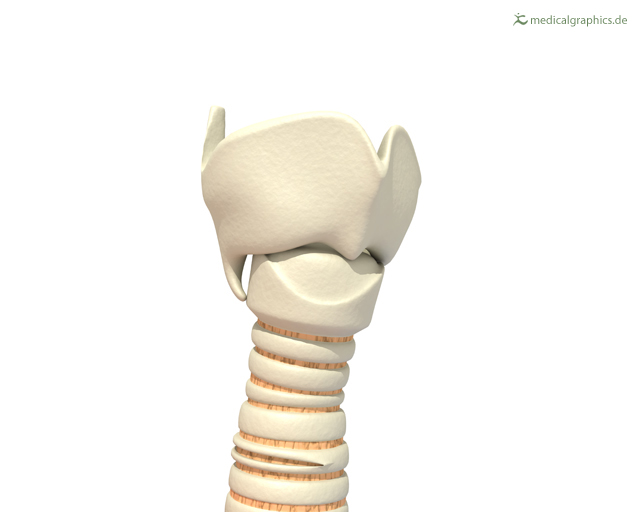

The larynx connects the pharynx and trachea, and helps to conduct air through the respiratory tract. The larynx is also called the voice box, because it contains the vocal cords, which vibrate when air flows over them, thereby producing sound. You can see the vocal cords in the larynx in Figures 13.2.3 and 13.2.4. Certain muscles in the larynx move the vocal cords apart to allow breathing. Other muscles in the larynx move the vocal cords together to allow the production of vocal sounds. The latter muscles also control the pitch of sounds and help control their volume.

|

Figure 13.2.4 The larynx as viewed from the top. |

A very important function of the larynx is protecting the trachea from aspirated food. When swallowing occurs, the backward motion of the tongue forces a flap called the epiglottis to close over the entrance to the larynx. (You can see the epiglottis in both Figure 13.2.3 and 13.2.4.) This prevents swallowed material from entering the larynx and moving deeper into the respiratory tract. If swallowed material does start to enter the larynx, it irritates the larynx and stimulates a strong cough reflex. This generally expels the material out of the larynx, and into the throat.

Larynx Model – Respiratory System, Dr. Lotz, 2018.

Lower Respiratory Tract

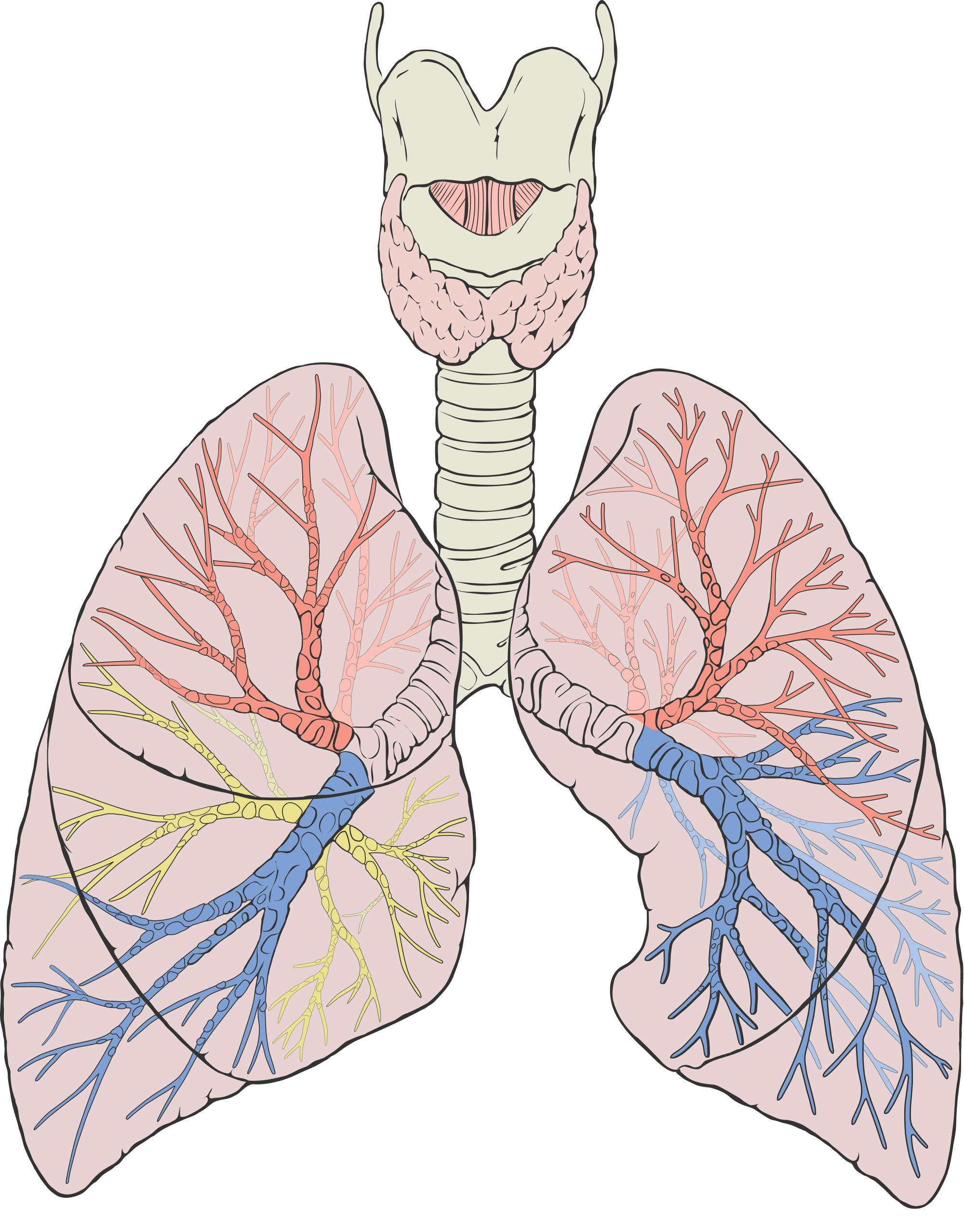

The trachea and other passages of the lower respiratory tract conduct air between the upper respiratory tract and the lungs. These passages form an inverted tree-like shape (Figure 13.2.5), with repeated branching as they move deeper into the lungs. All told, there are an astonishing 2,414 kilometres (1,500 miles) of airways conducting air through the human respiratory tract! It is only in the lungs, however, that gas exchange occurs between the air and the bloodstream.

Trachea

The trachea, or windpipe, is the widest passageway in the respiratory tract. It is about 2.5 cm wide and 10-15 cm long (approximately 1 inch wide and 4–6 inches long). It is formed by rings of cartilage, which make it relatively strong and resilient. The trachea connects the larynx to the lungs for the passage of air through the respiratory tract. The trachea branches at the bottom to form two bronchial tubes.

Bronchi and Bronchioles

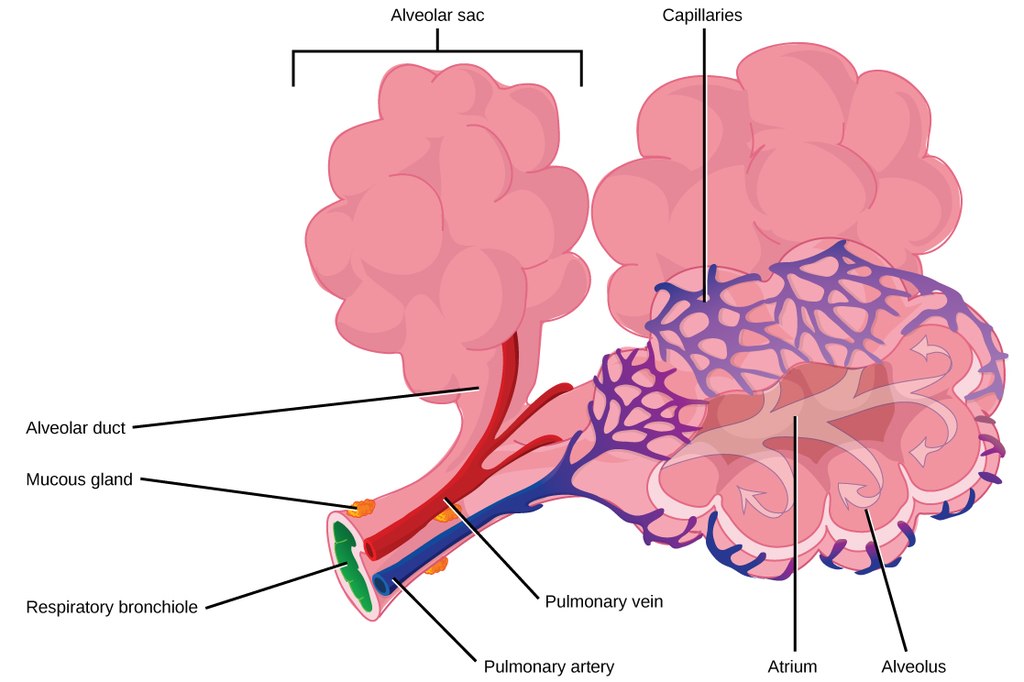

There are two main bronchial tubes, or bronchi (singular, bronchus), called the right and left bronchi. The bronchi carry air between the trachea and lungs. Each bronchus branches into smaller, secondary bronchi; and secondary bronchi branch into still smaller tertiary bronchi. The smallest bronchi branch into very small tubules called bronchioles. The tiniest bronchioles end in alveolar ducts, which terminate in clusters of minuscule air sacs, called alveoli (singular, alveolus), in the lungs.

Lungs

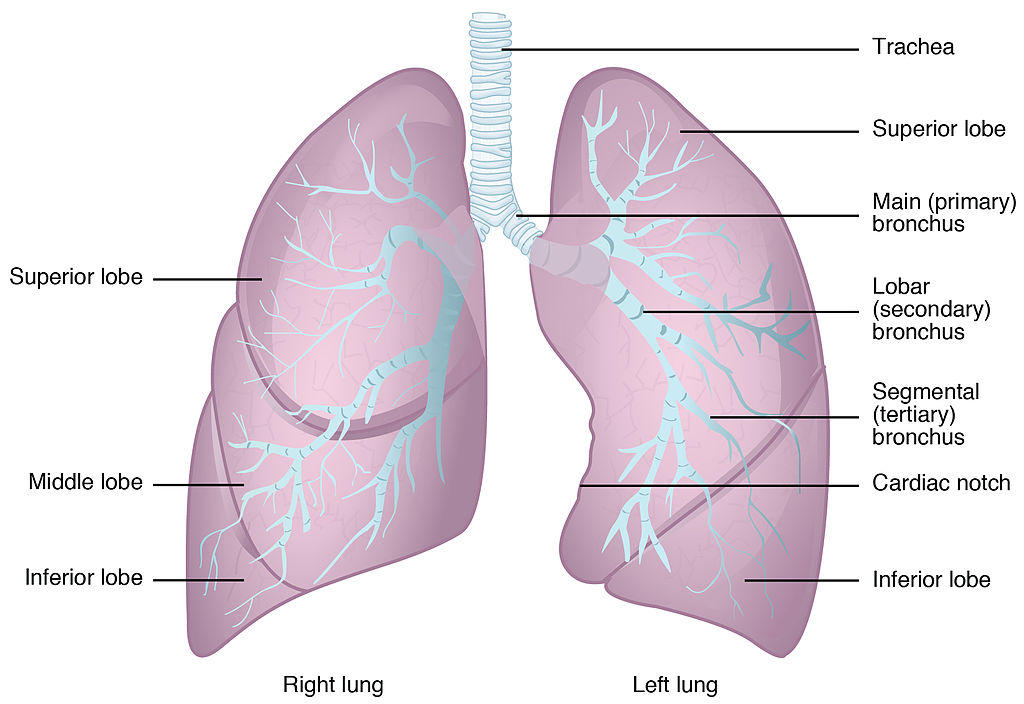

The lungs are the largest organs of the respiratory tract. They are suspended within the pleural cavity of the thorax. The lungs are surrounded by two thin membranes called pleura, which secrete fluid that allows the lungs to move freely within the pleural cavity. This is necessary so the lungs can expand and contract during breathing. In Figure 13.2.6, you can see that each of the two lungs is divided into sections. These are called lobes, and they are separated from each other by connective tissues. The right lung is larger and contains three lobes. The left lung is smaller and contains only two lobes. The smaller left lung allows room for the heart, which is just left of the center of the chest.

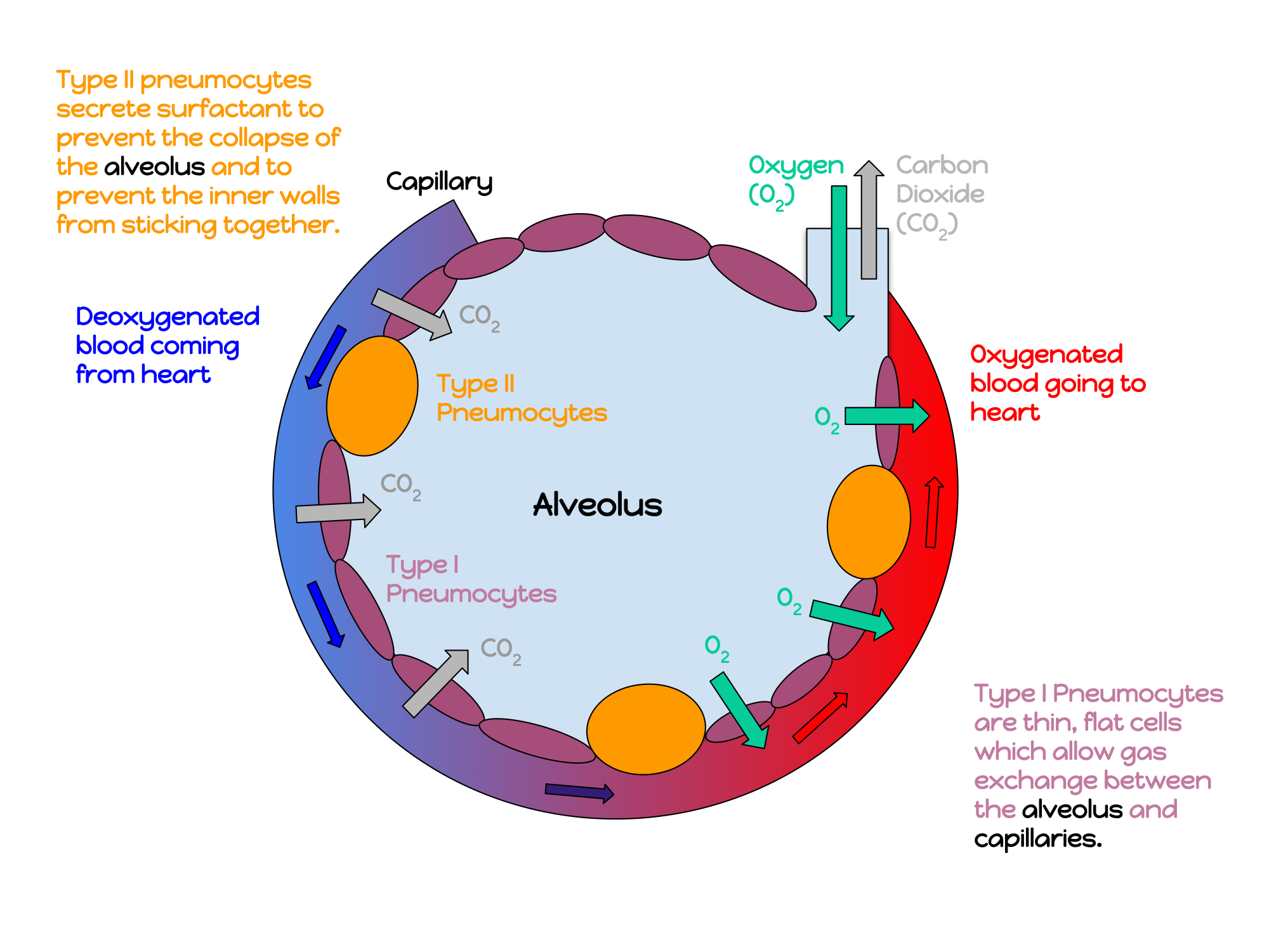

As mentioned previously, the bronchi terminate in bronchioles which feed air into alveoli, tiny sacs of simple squamous epithelial tissue which make up the bulk of the lung. The cross-section of lung tissue in the diagram below (Figure 13.2.7) shows the alveoli, in which gas exchange takes place with the capillary network that surrounds them.

|

|

Lung tissue consists mainly of alveoli (see Figures 13.2.7 and 13.2.8). These tiny air sacs are the functional units of the lungs where gas exchange takes place. The two lungs may contain as many as 700 million alveoli, providing a huge total surface area for gas exchange to take place. In fact, alveoli in the two lungs provide as much surface area as half a tennis court! Each time you breathe in, the alveoli fill with air, making the lungs expand. Oxygen in the air inside the alveoli is absorbed by the blood via diffusion in the mesh-like network of tiny capillaries that surrounds each alveolus. The blood in these capillaries also releases carbon dioxide (also by diffusion) into the air inside the alveoli. Each time you breathe out, air leaves the alveoli and rushes into the outside atmosphere, carrying waste gases with it.

The lungs receive blood from two major sources. They receive deoxygenated blood from the right side of the heart. This blood absorbs oxygen in the lungs and carries it back to the left side heart to be pumped to cells throughout the body. The lungs also receive oxygenated blood from the heart that provides oxygen to the cells of the lungs for cellular respiration.

Protecting the Respiratory System

You may be able to survive for weeks without food and for days without water, but you can survive without oxygen for only a matter of minutes — except under exceptional circumstances — so protecting the respiratory system is vital. Ensuring that a patient has an open airway is the first step in treating many medical emergencies. Fortunately, the respiratory system is well protected by the ribcage of the skeletal system. The extensive surface area of the respiratory system, however, is directly exposed to the outside world and all its potential dangers in inhaled air. It should come as no surprise that the respiratory system has a variety of ways to protect itself from harmful substances, such as dust and pathogens in the air.

The main way the respiratory system protects itself is called the mucociliary escalator. From the nose through the bronchi, the respiratory tract is covered in epithelium that contains mucus-secreting goblet cells. The mucus traps particles and pathogens in the incoming air. The epithelium of the respiratory tract is also covered with tiny cell projections called cilia (singular, cilium), as shown in the animation. The cilia constantly move in a sweeping motion upward toward the throat, moving the mucus and trapped particles and pathogens away from the lungs and toward the outside of the body. The upward sweeping motion of cilia lining the respiratory tract helps keep it free from dust, pathogens, and other harmful substances.

Watch “Mucociliary clearance” by I-Hsun Wu to learn more:

Mucociliary clearance, I-Hsun Wu, 2015.

Sneezing is a similar involuntary response that occurs when nerves lining the nasal passage are irritated. It results in forceful expulsion of air from the mouth, which sprays millions of tiny droplets of mucus and other debris out of the mouth and into the air, as shown in Figure 13.2.9. This explains why it is so important to sneeze into a tissue (rather than the air) if we are to prevent the transmission of respiratory pathogens.

How the Respiratory System Works with Other Organ Systems

The amount of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood must be maintained within a limited range for survival of the organism. Cells cannot survive for long without oxygen, and if there is too much carbon dioxide in the blood, the blood becomes dangerously acidic (pH is too low). Conversely, if there is too little carbon dioxide in the blood, the blood becomes too basic (pH is too high). The respiratory system works hand-in-hand with the nervous and cardiovascular systems to maintain homeostasis in blood gases and pH.

It is the level of carbon dioxide — rather than the level of oxygen — that is most closely monitored to maintain blood gas and pH homeostasis. The level of carbon dioxide in the blood is detected by cells in the brain, which speed up or slow down the rate of breathing through the autonomic nervous system as needed to bring the carbon dioxide level within the normal range. Faster breathing lowers the carbon dioxide level (and raises the oxygen level and pH), while slower breathing has the opposite effects. In this way, the levels of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and pH are maintained within normal limits.

The respiratory system also works closely with the cardiovascular system to maintain homeostasis. The respiratory system exchanges gases with the outside air, but it needs the cardiovascular system to carry them to and from body cells. Oxygen is absorbed by the blood in the lungs and then transported through a vast network of blood vessels to cells throughout the body, where it is needed for aerobic cellular respiration. The same system absorbs carbon dioxide from cells and carries it to the respiratory system for removal from the body.

Feature: My Human Body

Choking due to a foreign object becoming lodged in the airway results in nearly 5 thousand deaths in Canada each year. In addition, choking accounts for almost 40% of unintentional injuries in infants under the age of one. For the sake of your own human body, as well as those of loved ones, you should be aware of choking risks, signs, and treatments.

Choking is the mechanical obstruction of the flow of air from the atmosphere into the lungs. It prevents breathing, and may be partial or complete. Partial choking allows some — though inadequate — air flow into the lungs. Prolonged or complete choking results in asphyxia, or suffocation, which is potentially fatal.

Obstruction of the airway typically occurs in the pharynx or trachea. Young children are more prone to choking than are older people, in part because they often put small objects in their mouth and do not understand the risk of choking that they pose. Young children may choke on small toys or parts of toys, or on household objects, in addition to food. Foods that are round (hotdogs, carrots, grapes) or can adapt their shape to that of the pharynx (bananas, marshmallows), are especially dangerous, and may cause choking in adults, as well as children.

How can you tell if a loved one is choking? The person cannot speak or cry out, or has great difficulty doing so. Breathing, if possible, is laboured, producing gasping or wheezing. The person may desperately clutch at his or her throat or mouth. If breathing is not soon restored, the person’s face will start to turn blue from lack of oxygen. This will be followed by unconsciousness, brain damage, and possibly death if oxygen deprivation continues beyond a few minutes.

If an infant is choking, turning the baby upside down and slapping him on the back may dislodge the obstructing object. To help an older person who is choking, first encourage the person to cough. Give them a few hard back slaps to help force the lodged object out of the airway. If these steps fail, perform the Heimlich maneuver on the person. See the series of videos below, from ProCPR, which demonstrate several ways to help someone who is choking based on age and consciousness.

Conscious Adult Choking, ProCPR, 2016.

Unconscious Adult Choking, ProCPR, 2011.

Conscious Child Choking, ProCPR, 2009.

Unconscious Child Choking, ProCPR, 2009.

Conscious Infant Choking, ProCPR, 2011.

Unconscious Infant Choking, ProCPR, 2011.

13.2 Summary

- Respiration is the process in which oxygen moves from the outside air into the body, and in which carbon dioxide and other waste gases move from inside the body into the outside air. It involves two subsidiary processes: ventilation and gas exchange. Respiration is carried out mainly by the respiratory system.

- The organs of the respiratory system form a continuous system of passages, called the respiratory tract. It has two major divisions: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract.

- The upper respiratory tract includes the nasal cavity, pharynx, and larynx. All of these organs are involved in conduction, or the movement of air into and out of the body. Incoming air is also cleaned, humidified, and warmed as it passes through the upper respiratory tract. The larynx is called the voice box, because it contains the vocal cords, which are needed to produce vocal sounds.

- The lower respiratory tract includes the trachea, bronchi and bronchioles, and the lungs. The trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles are involved in conduction. Gas exchange takes place only in the lungs, which are the largest organs of the respiratory tract. Lung tissue consists mainly of tiny air sacs called alveoli, which is where gas exchange takes place between air in the alveoli and the blood in capillaries surrounding them.

- The respiratory system protects itself from potentially harmful substances in the air by the mucociliary escalator. This includes mucus-producing cells, which trap particles and pathogens in incoming air. It also includes tiny hair-like cilia that continually move to sweep the mucus and trapped debris away from the lungs and toward the outside of the body.

- The level of carbon dioxide in the blood is monitored by cells in the brain. If the level becomes too high, it triggers a faster rate of breathing, which lowers the level to the normal range. The opposite occurs if the level becomes too low. The respiratory system exchanges gases with the outside air, but it needs the cardiovascular system to carry the gases to and from cells throughout the body.

13.2 Review Questions

-

- What is respiration, as carried out by the respiratory system? Name the two subsidiary processes it involves.

- Describe the respiratory tract.

- Identify the organs of the upper respiratory tract. What are their functions?

- List the organs of the lower respiratory tract. Which organs are involved only in conduction?

- Where does gas exchange take place?

- How does the respiratory system protect itself from potentially harmful substances in the air?

- Explain how the rate of breathing is controlled.

- Why does the respiratory system need the cardiovascular system to help it perform its main function of gas exchange?

- Describe two ways in which the body prevents food from entering the lungs.

- What is the relationship between respiration and cellular respiration?

13.2 Explore More

How do lungs work? – Emma Bryce, TED-Ed, 2014.

Why Do Men Have Deeper Voices? BrainStuff – HowStuffWorks, 2015.

Why does your voice change as you get older? – Shaylin A. Schundler, TED-Ed, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 13.2.1

Exhale by pavel-lozovikov-HYovA7yPPvI [photo] by Pavel Lozovikov on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 13.2.2

Illu_conducting_passages.svg by Lord Akryl, Jmarchn from SEER Training Modules/ National Cancer Institute on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 13.2.3

Larynx by www.medicalgraphics.de is used under a CC BY-ND 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/) license.

Figure 13.2.4

Larynx top view by Alan Hoofring (Illustrator) for National Cancer Institute is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 13.2.5

2000px-Lungs_diagram_detailed.svg by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5) license. (Derivative work of Fruchtwasserembolie.png.)

Figure 13.2.6

Gross_Anatomy_of_the_Lungs by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 13.2.7

Alveoli Structure by CNX OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 13.2.8

annotated_diagram_of_an_alveolus.svg by Katherinebutler1331 on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 13.2.9

Sneeze by James Gathany at CDC Public Health Imagery Library (PHIL) #11162 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 22.2 Major respiratory structures [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 22.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/22-1-organs-and-structures-of-the-respiratory-system [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)].

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 22.13 Gross anatomy of the lungs [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 22.2). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/22-2-the-lungs

BrainStuff – HowStuffWorks. (2015, December 1). Why do men have deeper voices? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6iFPs6JlSzY&feature=youtu.be

Dr. Lotz. (2018, January 25). Larynx model – Respiratory system. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BsyB88mq5rQ&feature=youtu.be

I-Hsun Wu. (2015, March 31). Mucociliary clearance. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HMB6flEaZwI&feature=youtu.be

OpenStax. (2016, May 27). Figure 9 Terminal bronchioles are connected by respiratory bronchioles to alveolar ducts and alveolar sacs [digital image]. In OpenStax, Biology (Section 39.1). OpenStax CNX. https://cnx.org/contents/GFy_h8cu@10.53:35-R0biq@11/Systems-of-Gas-Exchange

ProCPR. (2009, November 24). Conscious child choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZjmbD7aIaf0&feature=youtu.be

ProCPR. (2009, November 24).Unconscious child choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sba0T2XGIn4&feature=youtu.be

ProCPR. (2011, February 1). Conscious infant choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axqIju9CLKA&feature=youtu.be

ProCPR. (2011, February 1). Unconscious adult choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5kmsKNvKAvU&feature=youtu.be

ProCPR. (2011, February 1). Unconscious infant choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_K7Dwy6b2wQ&feature=youtu.be

ProCPR. (2016, April 8). Conscious adult choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XOTbjDGZ7wg&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2014, November 24). How do lungs work? – Emma Bryce. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8NUxvJS-_0k&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2018, August 2). Why does your voice change as you get older? – Shaylin A. Schundler. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjibeBSnpJ0&feature=youtu.be

The exchange of gases between the body and the outside air.

The body system responsible for taking in oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide. The primary organs of the respiratory system are the lungs, which carry out this exchange of gases as we breathe.

A set of metabolic reactions and processes that take place in the cells of organisms to convert biochemical energy from nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

Relating to, involving, or requiring free oxygen.

The process of moving air into and out of the lungs; also called breathing.

Biological process through which gases are transferred across cell membranes to either enter or leave the blood.

The continuous system of passages through which air flows into and out of the body.

Refers to following airway structures: nasal cavities and passages (sinuses), pharynx, tonsils, and larynx (voice box).

Refers to following airway structures: trachea (windpipe) and lungs with its substructures bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli.

A large, dome-shaped muscle below the lungs that allows breathing to occur when it alternately contracts and relaxes.

The movement of air into and out of the body.

A large, air-filled space in the skull above and behind the nose that helps conduct air in and out of the body as part of the upper respiratory tract.

The part of the human skeleton that provides a bony framework for the head and includes bones of the cranium and face.

Epithelial tissue that lines inner body surfaces and body openings and produces mucus.

A type of sensory receptor that responds to presence of chemicals.

A chemoreception (ability to detect the presence of certain chemicals) that, through the sensory olfactory system, forms the perception of smell.

The perception produced or stimulated when a substance in the mouth reacts chemically with taste receptor cells located on taste buds in the oral cavity, mostly on the tongue.

Tubular organ that connects the mouth and nasal cavity with the larynx and through which air and food pass.

The opening in the lower part of the human face, surrounded by the lips, through which food is taken in and from which speech and other sounds are emitted.

An organ of the respiratory system between the pharynx and trachea, also called the voice box because it contains the vocal cords that allow the production of vocal sounds.

The portion of the respiratory (breathing) tract containing the vocal cords which produce sound.

Two folded pairs of membranes in the larynx (voice box) that vibrate when air that is exhaled passes through them, producing sound.

A flap of cartilage at the root of the tongue, which is depressed during swallowing to cover the opening of the windpipe.

A tubular organ of the respiratory system that carries air between the larynx and bronchi; also called windpipe.

One of many tubes of various sizes that carry air between the trachea and the alveoli in the lungs.

Any of the minute branches into which a bronchus divides.

One of a cluster of tiny sacs at the ends of bronchioles in the lungs where pulmonary gas exchange takes place.

Two paired organs of the respiratory system in which gas exchange takes place between the blood and the atmosphere.

Each of a pair of serous membranes lining the thorax and enveloping the lungs.

bony “cage” enclosing the thoracic cavity and consisting of the ribs, thoracic vertebrae, and sternum

Term for the apparatus of mucus and cilia responsible for movement of mucus up and out of the respiratory tract. Mucus traps particles and cilia propel mucus up and out of the lungs where the fluid and mucus is then swallowed and the debris eliminated by the digestive system.

Tiny hairlike organelles, identical in structure to flagella, that line the surfaces of certain cells and beat in rhythmic waves, providing locomotion to ciliate protozoans and moving liquids along internal epithelial tissue in animals.

Having a higher proportion of hydronium ions than hydroxide ions; having the properties of an acid; having a pH below 7.

The highly complex body system of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes that impact the body, then works in tandem with the endocrine system to respond to such events.

Refers to the body system consisting of the heart, blood vessels and the blood. Blood contains oxygen and other nutrients which your body needs to survive. The body takes these essential nutrients from the blood.

The ability of an organism to maintain constant internal conditions despite external changes.

The central nervous system organ inside the skull that is the control center of the nervous system.