12 2.5 The Human Animal

Created by CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Primate Pals

Figure 2.5.1 Humans and monkeys share an evolutionary past. Humans belong to the animal kingdom, which includes small organisms — like insects — and larger organisms, like humans and monkeys. From genes to morphology to behavior, humans and monkeys are similar in many ways because they share an evolutionary past. Humans and monkeys also both belong to the order Primate, which means they have more traits in common with each other than with insects.

How Humans Are Classified

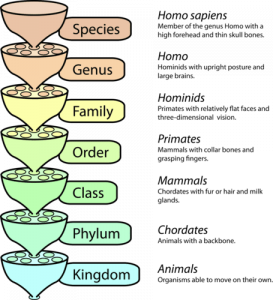

You probably know that modern humans are members of the species Homo sapiens. But what is our place in nature? How is our species classified? A simple classification is represented in the taxonomic diagram below, along with some representative characteristics.

Let’s start at the bottom of the chart, with the kingdom. Among other animal characteristics, humans can move on their own, so they are placed in the animal kingdom. Further, humans belong to the animal phylum known as chordates, because we have a backbone. The human animal has hair and milk glands, so we are placed in the class of mammals. Within the mammal class, humans are placed in the primate order.

Humans as Primates

Living members of the primate order include monkeys, apes, and humans. At some point in the distant past, we shared ape-like ancestors with all of these modern groups of primates. We share between 93 and 99 per cent of our DNA sequences with them, which provides hard evidence that we have relatively recent common ancestors. Besides genes, what traits do we share with other primates?

Primates are considered generalists among the mammals. A generalist is an organism that can thrive in a wide variety of environmental conditions. Generalists also make use of a variety of different resources; for example, they consume many types of food. Although primates exhibit a wide range of characteristics, there are several traits shared by most primates.

Primate Traits

Primates have pentadactylism, or five digits (fingers or toes) on each extremity (hand or foot). The fingers and toes have nails instead of claws and are covered with sensitive tactile pads. The thumbs (and in many species, the big toes, as well) are opposable, which means they can be brought into opposition with the other digits, allowing both a power grasp and a precision grip. You can see these features of the primate extremities in the capuchin monkey pictured in Figure 2.15.

The five fingers, opposable thumb, and other primate features of the hand give this capuchin monkey great manual dexterity. This is the primary reason these primates are trained to assist quadraplegic human beings with daily tasks.

The primate body is generally semi-erect or erect, and primates have one of several modes of locomotion, including walking on all four legs (quadrupedalism), vertical clinging and leaping, swinging from branch to branch in trees (brachiation), or walking on two legs (bipedalism, which today only applies to humans). The primate shoulder girdle has a collar bone (clavicle), which is associated with a wide range of motion of the upper limbs.

Relative to other mammals, primates rely less on their sense of smell. They have a reduced snout and relatively small area in the brain for processing olfactory (odor) information. Primates rely more on their sense of vision, which shows several improvements over that of other mammals. Most primates can see in colour. Primates also tend to have large eyes with forward placement in a relatively flat face. This results in an overlap of the visual fields of the two eyes, allowing stereoscopic (or three-dimensional) vision. Other indications of the importance of vision to primates is the protection given the eyes by a complete bony eye socket and the large size of the occipital lobe of the brain, where visual information is processed.

Primates are noted for their relatively large brains, high degree of intelligence, and complex behaviors. The part of the brain that is especially enlarged in primates is the cerebrum, which analyzes and synthesizes sensory information and transforms it to motor behaviors appropriate to the environment. Primates tend to have longer lifespans than most other mammals. In particular, there is a lengthening of the prenatal period and the postnatal period during which infants depend on adults, providing an extended opportunity for learning among juveniles. Most primates live in social groups. In fact, primates are among the most social of animals. Depending on the species, adult nonhuman primates may live in mated pairs or in groups with hundreds of members. Humans and some nonhuman primates can also make and use tools. The crab-eating macaques pictured below provide examples of tool use in nonhuman primates.

Life in the Trees

Scientists think that many primate traits are adaptations to an arboreal (or tree-dwelling) lifestyle. Primates are thought to have evolved in trees, and the majority of primates still live in trees. For life in the trees, the sense of vision trumps the sense of smell, and three-dimensional (3D) vision is especially important for grasping the next branch or limb. Having mobile limbs, a good grip, and manual dexterity are matters of life and death when one lives high above the ground. While some modern primates are mainly terrestrial (ground dwelling) rather than arboreal, all primates possess adaptations for life in the trees.

The map to the left shows the present distribution of nonhuman primates around the world. Tropical forests in Central and South America are home to many species of monkeys, including the squirrel monkey pictured above. Old World tropical forests in Africa and Asia are home to many other species of monkeys, including the crab-eating macaque pictured above, as well as all modern apes.

Humans as Hominids

Who are our closest relatives in the primate order? We are placed in the family called Hominidae. Any member of this family is called a hominid. Hominids include four living genera: chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and humans. Among these four genera are just seven living species: two in each genera, except humans, with our sole living species, Homo sapiens. The orangutan mother pictured cradling her child shows how similar these hominids are to us.

Hominids are relatively large, tailless primates, ranging in size from the bonobo (or pygmy chimpanzee) — which may weigh as little as 30 kg (66 lb) — to the eastern gorilla, which may weigh over 200 kg (440 lb). Most modern humans fall somewhere within that range. In all species of hominids, males are somewhat larger and stronger, on average, than females, but the differences may not be significant. Except for humans, hominids are mainly quadrupedal, although they can get around bipedally if need be to gather food or nesting materials. Humans are the only habitually bipedal species of living hominids.

The Human Genus

Within the hominid family, our species is placed in the genus Homo. Our species, Homo sapiens, is the only living species in this genus. Several earlier species of Homo existed, but have since gone extinct, including the species Homo erectus.

By about 2.8 million years ago, early Homo species such as Homo erectus were probably nearly as efficient at bipedal locomotion as modern humans. Relative to quadrupedal primates, they had a broader pelvis, longer legs, and arched feet. However, from the neck up, they were still quite different from us. They typically had bigger jaws and teeth, a sloping forehead, and a relatively small brain.

Homo sapiens

During the roughly 2.8 million years of the evolution of the Homo genus, the remaining features of Homo sapiens evolved. These features include:

- Small front teeth (incisors and canines) with relatively large molars, at least compared to other primates.

- A decrease in the size of the jaws and face and an increase in the size of the cranium, forming a nearly vertical forehead.

- A tremendous enlargement of the brain, especially in the cerebrum, which is the site of higher intellectual functions.

The increase in brain size occurred very rapidly as far as evolutionary change goes, between about 800 thousand and 100 thousand years ago. During this period, the size of the brain increased from about 600 cm3 to about 1400 cm3 when the earliest Homo sapiens appeared. This was also a period of rapid climate change, and many scientists think that climate change was a major impetus for the evolution of a larger, more complex brain. In this view, as the environment became more unpredictable, bigger and “smarter” brains helped our ancestors survive. Running parallel to the biological evolution of the brain was the development of culture and technology, which were adapted for the purpose of exploiting the environment. These developments, made possible by a big brain, allowed modern humans and their recent ancestors to occupy virtually the entire world and become the dominant land animals.

Our species Homo sapiens is the most recent iteration of the basic primate body plan. Because of our big, complex brain, we clearly have a much greater capacity for abstract thought and technological advances than any other primate — even chimpanzees, who are our closest living relatives. However, it is important to recognize that in other ways, we are not as adept as other living hominids around the world. We are physically weaker than gorillas, far less agile than orangutans, and arguably less well-mannered than bonobos.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

Imagine squeezing through a 7-inch slit in rock to enter a completely dark cave full of lots and lots of old bones. It might sound like a nightmare to most people, but it was a necessary part of a recent exploration of human origins in South Africa as reported in the New York Times in September 2015. The cave and its bones were actually first discovered by spelunkers in 2013, who reported it to paleontologists. An international research project was soon launched to explore the cave. The researchers would eventually conclude that the cave was a hiding place for the dead of a previously unknown early species of Homo, whom they called Homo naledi. Members of this species lived in South Africa around 2.5 to 2.8 million years ago.

Homo naledi individuals were about 5 feet (about 1.5 metres) tall and weighed around 100 pounds (about 45 kilograms), so they probably had no trouble squeezing into the cave. Modern humans are considerably larger on average. In order to retrieve the fossilized bones from the cave, six slender researchers had to be found on social media. They were the only ones who could fit through the crack to access the cave. The work was difficult and dangerous, but also incredibly exciting. The site constitutes one of the largest samples of any extinct early Homo species anywhere in the world, and the fossils represent a completely new species of that genus. The site also suggests that early members of our genus were intentionally depositing their dead in a remote place. This behavior was previously thought to be limited to later humans.

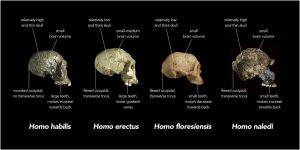

Like other early Homo species, Homo naledi exhibits a mosaic of old and modern traits. From the neck down, these early hominins were well-adapted for upright walking. Their feet were virtually indistinguishable from modern human feet and their legs were also long like ours. Homo naledi had relatively small front teeth, but also a small brain, no larger than an average orange. Clearly, the spurt in brain growth in Homo did not occur in this species. The image to the left shows the different morphology of early human skulls.

Watch the news for more exciting updates about this early species of our genus. Paleontologists researching the cave site estimate that there are hundreds — if not thousands — of fossilized bones still remaining in the cave. There are sure to be many more discoveries reported in the news media about this extinct Homo species.

2.5 Summary

- The human species, Homo sapiens, is placed in the primate order of the class of mammals, which are chordates in the animal kingdom.

- Humans share many traits with other primates. They have five digits with nails and opposable thumbs; an excellent sense of vision, including the ability to see in colour and stereoscopic vision; a large brain, high degree of intelligence, and complex behaviors. Like most other primates, we also live in social groups. Many of our primate traits are adaptations to life in the trees.

- Within the primate order, our species is placed in the hominid family, which also includes chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans. All hominids are relatively large, tailless primates, in which males are generally bigger than females.

- The genus Homo first evolved about 2.8 million years ago. Early Homo species were fully bipedal, but had small brains. All are now extinct.

- During the last 800 thousand years, Homo sapiens evolved, with smaller faces, jaws, and front teeth, but much bigger brains than earlier Homo species.

2.5 Review Questions

- Outline how humans are classified. Name their taxa, starting with the kingdom and ending with the species.

- List several primate traits. Explain how they are related to a life in the trees.

-

- What are hominids? Describe how living hominids are classified.

- Discuss species in the genus Homo.

- Relate climatic changes to the evolution of the genus Homo over the last million years.

- Why is it significant that we share 93% to 99% of our DNA sequence with other primates?

- Which species do you think we are more likely to share a greater amount of DNA sequence with — non-primate mammals (i.e. horses) or non-mammalian chordates (i.e. frogs)? Explain your answer.

- What is the relationship between shared DNA and shared traits?

- Compared to other mammals, primates have a relatively small area of their brain dedicated to olfactory processing. What does this tell you about the sense of smell in primates compared to other mammals? Why?

- Why do you think it is interesting that nonhuman primates can use tools?

- Explain why the discovery of Homo naledi was exciting.

2.5 Explore More

Helping Hands: Matching Capuchins with Those in Need, from BUToday, 2009.

New human ancestor discovered: homo naledi (EXCLUSIVE VIDEO)

by National Geographic, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 2.5.1

Macaca nigra self-portrait on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain). (As the work was created from a non-human animal, it has no human author in whom copyright is vested – See the Wtop.com news article.)

Figure 2.5.2

Classification of the human species, by Christopher Auyeung (based on original image from Peter Halasz on Wikimedia Commons), CK-12 Foundation, is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/) license. (Original image in public domain).

Figure 2.5.3

Stone tool use by a capuchin monkey, by Tiago Falótico , is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/) license.

Figure 2.5.4

Macaca fascicularis aurea stone tools, by Haslam M, Gumert MD, Biro D, Carvalho S, Malaivijitnond S, Figure 2, PLOS One, 2013, is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/) license.

Figure 2.5.5

Squirrel monkey, on Max Pixel, is used under a CC0 1.0 (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en) universal public domain dedication license.

Figure 2.5.6

Non-human primate range [map], by Jackhynes, 2008, is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 2.5.7

Baby Orangutan 3, by Tony Hisgett, 2012, on Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 2.5.8

Homo erectus, by Emőke Dénes, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/) license.

Figure 2.5.9

Comparison of skull features of Homo naledi and other early human species, by Chris Stringer, Natural History Museum, United Kingdom, 2015, is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) license.

References

BUToday. (2009, October 5). Helping hands: matching capuchins with those in need. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vRzp9O9Qc1o&feature=youtu.be

Kelleher, C. (2014, August 22). Monkey ‘selfie’ copyright issue settled [online article]. WTOP.com/News. https://wtop.com/news/2014/08/monkey-selfie-copyright-issue-settled/

National Geographic. (2015, September 5). New human ancestor discovered: homo naledi (EXCLUSIVE VIDEO) | National Geographic. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oxgnlSbYLSc&feature=youtu.be

A groups of mammals characterized by flexible hands and feet, each with five digits, including humans, great apes, monkeys, and lemurs.

An organism able to utilize many food sources and therefore able to flourish in many habitats.

Of, relating to, or being a member of a family (Hominidae) of erect, bipedal, primate mammals that includes recent humans together with extinct ancestral and related forms and in some recent classifications the gorilla, chimpanzee, and orangutan.