147 17.3 Lymphatic System

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Tonsillitis

The white patches on either side of the throat in Figure 17.3.1 are signs of tonsillitis. The tonsils are small structures in the throat that are very common sites of infection. The white spots on the tonsils pictured here are evidence of infection. The patches consist of large amounts of dead bacteria, cellular debris, and white blood cells — in a word: pus. Children with recurrent tonsillitis may have their tonsils removed surgically to eliminate this type of infection. The tonsils are organs of the lymphatic system.

What Is the Lymphatic System?

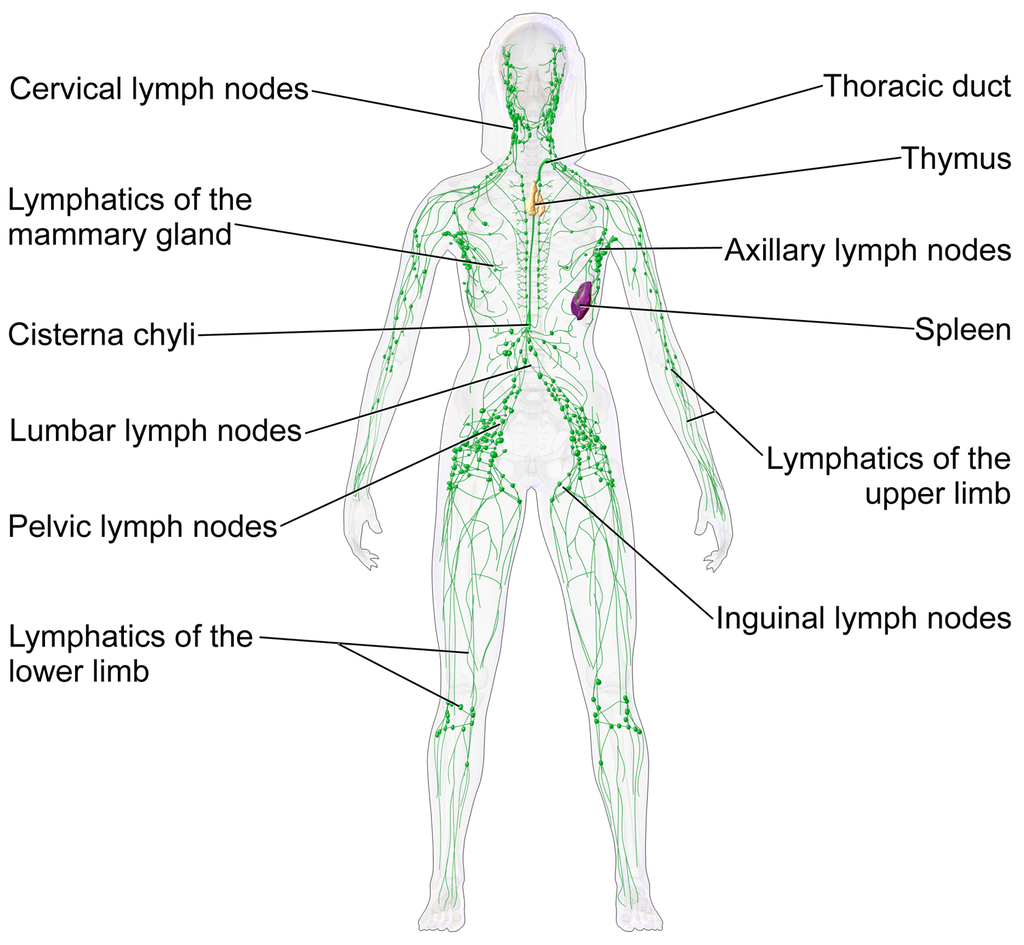

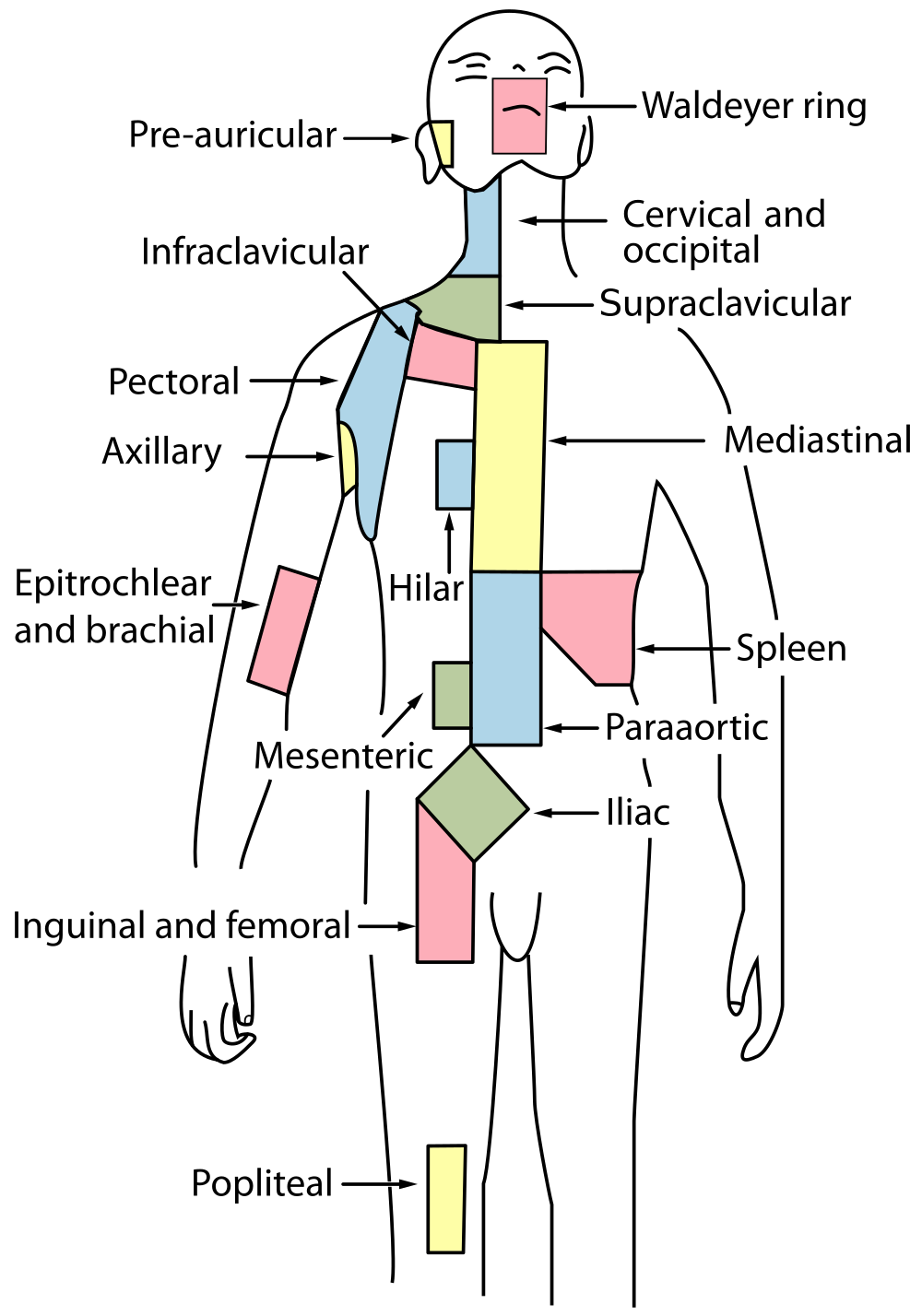

The lymphatic system is a collection of organs involved in the production, maturation, and harboring of white blood cells called lymphocytes. It also includes a network of vessels that transport or filter the fluid known as lymph in which lymphocytes circulate. Figure 17.3.2 shows major lymphatic vessels and other structures that make up the lymphatic system. Besides the tonsils, organs of the lymphatic system include the thymus, the spleen, and hundreds of lymph nodes distributed along the lymphatic vessels.

The lymphatic vessels form a transportation network similar in many respects to the blood vessels of the cardiovascular system. However, unlike the cardiovascular system, the lymphatic system is not a closed system. Instead, lymphatic vessels carry lymph in a single direction — always toward the upper chest, where the lymph empties from lymphatic vessels into blood vessels.

Cardiovascular Function of the Lymphatic System

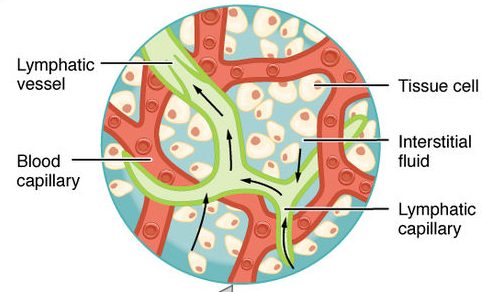

The return of lymph to the bloodstream is one of the major functions of the lymphatic system. When blood travels through capillaries of the cardiovascular system, it is under pressure, which forces some of the components of blood (such as water, oxygen, and nutrients) through the walls of the capillaries and into the tissue spaces between cells, forming tissue fluid, also called interstitial fluid (see Figure 17.3.3). Interstitial fluid bathes and nourishes cells, and also absorbs their waste products. Much of the water from interstitial fluid is reabsorbed into the capillary blood by osmosis. Most of the remaining fluid is absorbed by tiny lymphatic vessels called lymph capillaries. Once interstitial fluid enters the lymphatic vessels, it is called lymph. Lymph is very similar in composition to blood plasma. Besides water, lymph may contain proteins, waste products, cellular debris, and pathogens. It also contains numerous white blood cells, especially the subset of white blood cells known as lymphocytes. In fact, lymphocytes are the main cellular components of lymph.

The lymph that enters lymph capillaries in tissues is transported through the lymphatic vessel network to two large lymphatic ducts in the upper chest. From there, the lymph flows into two major veins (called subclavian veins) of the cardiovascular system. Unlike blood, lymph is not pumped through its network of vessels. Instead, lymph moves through lymphatic vessels via a combination of contractions of the vessels themselves and the forces applied to the vessels externally by skeletal muscles, similarly to how blood moves through veins. Lymphatic vessels also contain numerous valves that keep lymph flowing in just one direction, thereby preventing backflow.

Digestive Function of the Lymphatic System

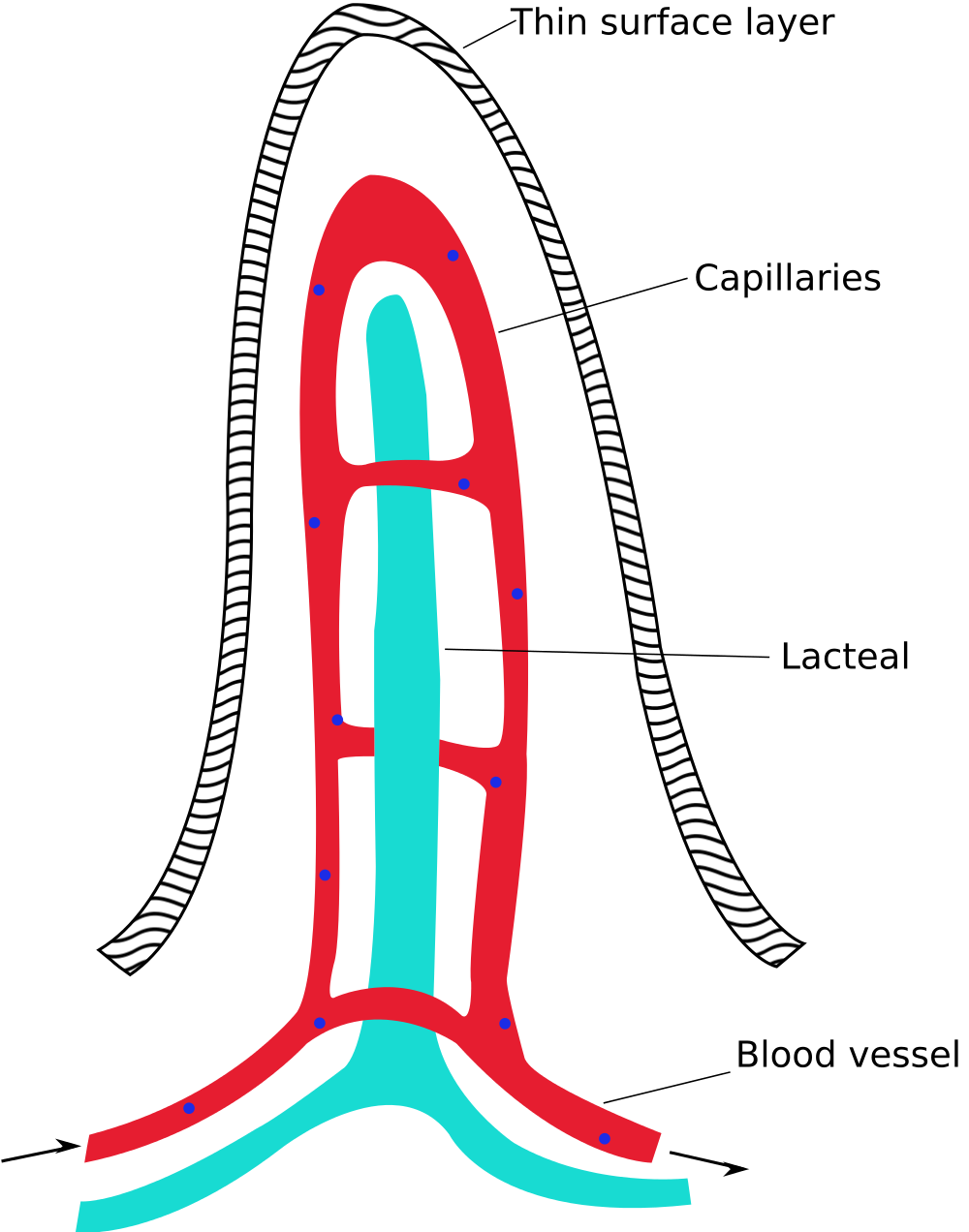

Lymphatic vessels called lacteals (see Figure 17.3.4) are present in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract, mainly in the small intestine. Each tiny villus in the lining of the small intestine has an internal bed of capillaries and lacteals. The capillaries absorb most nutrients from the digestion of food into the blood. The lacteals absorb mainly fatty acids from lipid digestion into the lymph, forming a fatty-acid-enriched fluid called chyle. Vessels of the lymphatic network then transport chyle from the small intestine to the main lymphatic ducts in the chest, from which it drains into the blood circulation. The nutrients in chyle then circulate in the blood to the liver, where they are processed along with the other nutrients that reach the liver directly via the bloodstream.

Immune Function of the Lymphatic System

The primary immune function of the lymphatic system is to protect the body against pathogens and cancerous cells. This function of the lymphatic system is centred on the production, maturation, and circulation of lymphocytes. Lymphocytes are leukocytes that are involved in the adaptive immune system. They are responsible for the recognition of — and tailored defense against — specific pathogens or tumor cells. Lymphocytes may also create a lasting memory of pathogens, so they can be attacked quickly and strongly if they ever invade the body again. In this way, lymphocytes bring about long-lasting immunity to specific pathogens.

There are two major types of lymphocytes, called B cells and T cells. Both B cells and T cells are involved in the adaptive immune response, but they play different roles.

Production and Maturation of Lymphocytes

Like all other types of blood cells (including erythrocytes), both B cells and T cells are produced from stem cells in the red marrow inside bones. After lymphocytes first form, they must go through a complicated maturation process before they are ready to search for pathogens. In this maturation process, they “learn” to distinguish self from non-self. Only those lymphocytes that successfully complete this maturation process go on to actually fight infections by pathogens.

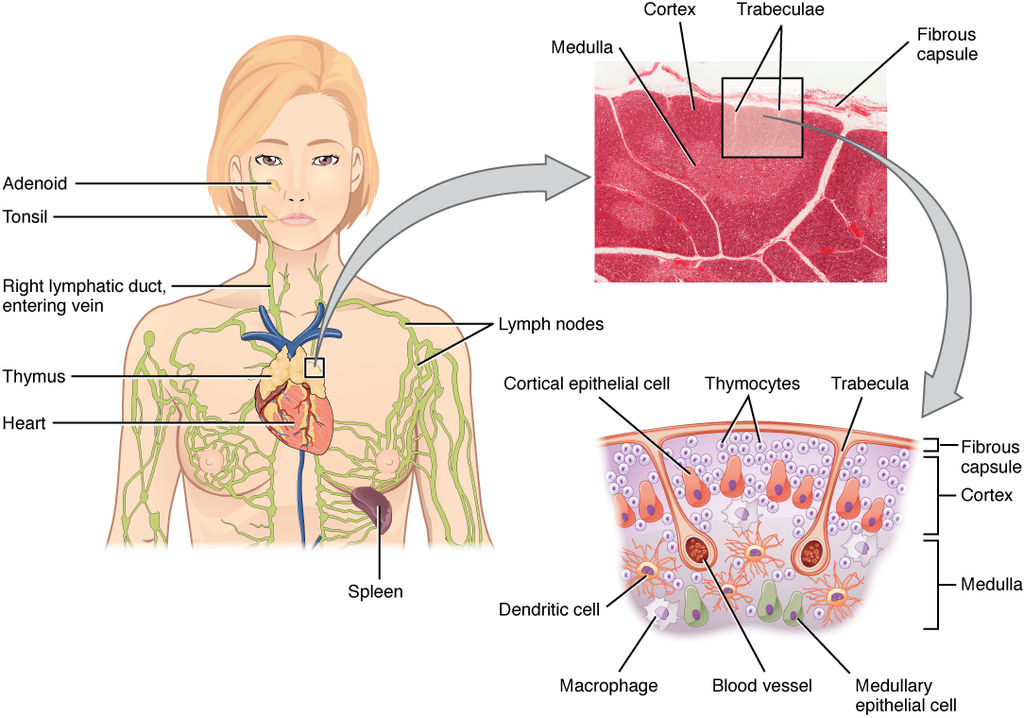

B cells mature in the bone marrow, which is why they are called B cells. After they mature and leave the bone marrow, they travel first to the circulatory system and then enter the lymphatic system to search for pathogens. T cells, on the other hand, mature in the thymus, which is why they are called T cells. The thymus is illustrated in Figure 17.3.5. It is a small lymphatic organ in the chest that consists of an outer cortex and inner medulla, all surrounded by a fibrous capsule. After maturing in the thymus, T cells enter the rest of the lymphatic system to join B cells in the hunt for pathogens. The bone marrow and thymus are called primary lymphoid organs because of their role in the production and/or maturation of lymphocytes.

Lymphocytes in Secondary Lymphoid Organs

The tonsils, spleen, and lymph nodes are referred to as secondary lymphoid organs. These organs do not produce or mature lymphocytes. Instead, they filter lymph and store lymphocytes. It is in these secondary lymphoid organs that pathogens (or their antigens) activate lymphocytes and initiate adaptive immune responses. Activation leads to cloning of pathogen-specific lymphocytes, which then circulate between the lymphatic system and the blood, searching for and destroying their specific pathogens by producing antibodies against them.

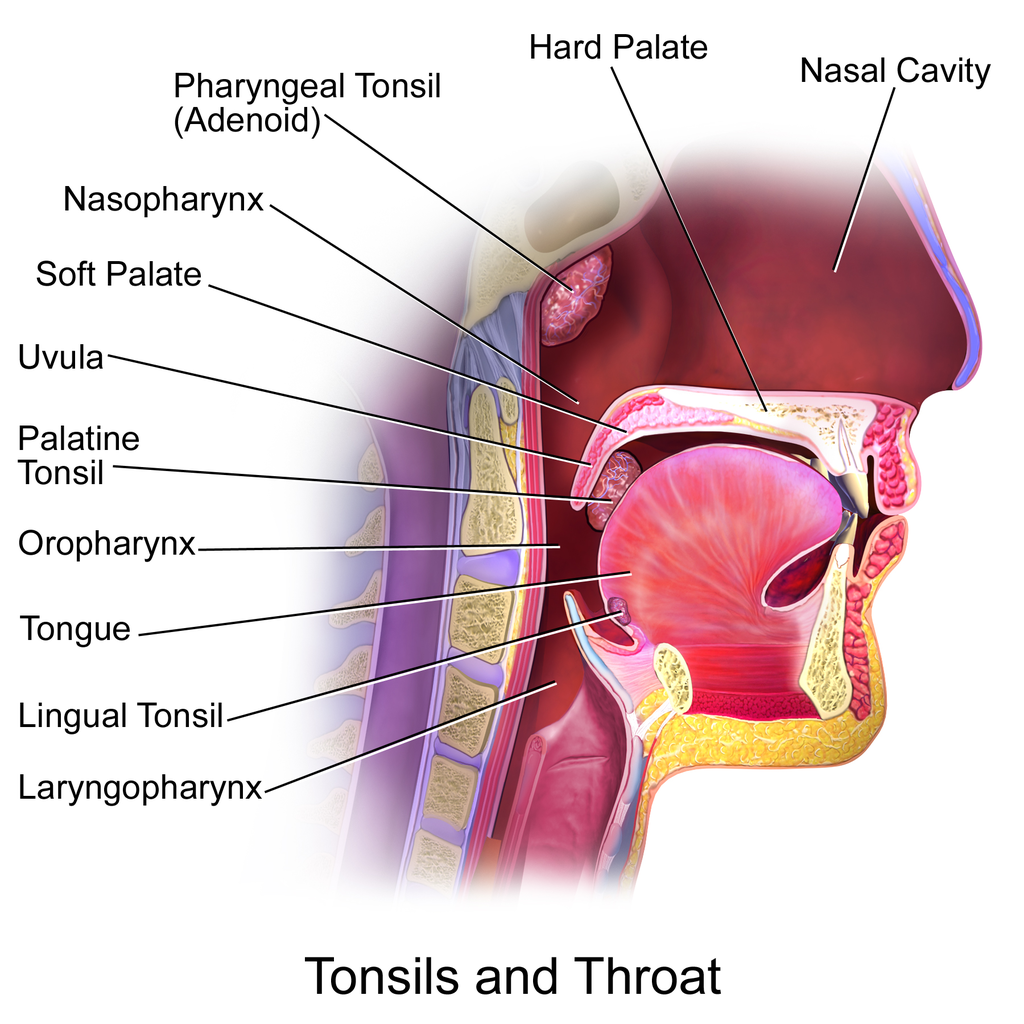

Tonsils

There are four pairs of human tonsils. Three of the four are shown in Figure 17.3.6. The fourth pair, called tubal tonsils, is located at the back of the nasopharynx. The palatine tonsils are the tonsils that are visible on either side of the throat. All four pairs of tonsils encircle a part of the anatomy where the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts intersect, and where pathogens have ready access to the body. This ring of tonsils is called Waldeyer’s ring.

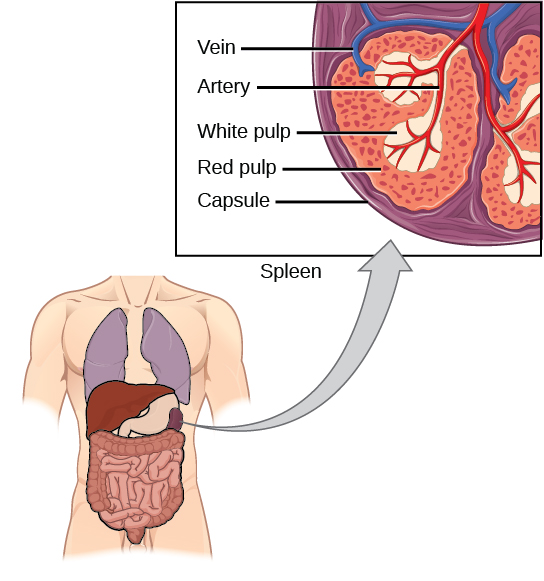

Spleen

The spleen (Figure 17.3.7) is the largest of the secondary lymphoid organs, and is centrally located in the body. Besides harboring lymphocytes and filtering lymph, the spleen also filters blood. Most dead or aged erythrocytes are removed from the blood in the red pulp of the spleen. Lymph is filtered in the white pulp of the spleen. In the fetus, the spleen has the additional function of producing red blood cells. This function is taken over by bone marrow after birth.

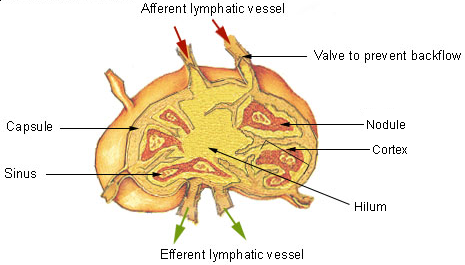

Lymph Nodes

Each lymph node is a small, but organized collection of lymphoid tissue (see Figure 17.3.8) that contains many lymphocytes. Lymph nodes are located at intervals along the lymphatic vessels, and lymph passes through them on its way back to the blood.

There are at least 500 lymph nodes in the human body. Many of them are clustered at the base of the limbs and in the neck. Figure 17.3.9 shows the major lymph node concentrations, and includes the spleen and the region named Waldeyer’s ring, which consists of the tonsils.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

When lymph nodes become enlarged and tender to the touch, they are obvious signs of immune system activity. Because it is easy to see and feel swollen lymph nodes, they are one way an individual can monitor his or her own health. To be useful in this way, it is important to know the myths and realities about swollen lymph nodes.

Myth

|

Reality

|

| “You should see a doctor immediately whenever you have swollen lymph nodes.” | Lymph nodes are constantly filtering lymph, so it is expected that they will change in size with varying amounts of debris or pathogens that may be present. A minor, unnoticed infection may cause swollen lymph nodes that may last for a few weeks. Generally, lymph nodes that return to their normal size within two or three weeks are not a cause for concern. |

| “Swollen lymph nodes mean you have a bacterial infection.” | Although an infection is the most common cause of swollen lymph nodes, not all infections are caused by bacteria. Mononucleosis, for example, commonly causes swollen lymph nodes, and it is caused by viruses. There are also other causes of swollen lymph nodes besides infections, such as cancer and certain medications. |

| “A swollen lymph node means you have cancer.” | Cancer is far less likely to be the cause of a swollen lymph node than is an infection. However, if a lymph node remains swollen longer than a few weeks — especially in the absence of an apparent infection — you should have your doctor check it. |

| “Cancer in a lymph node always originates somewhere else. There is no cancer of the lymph nodes.” | Cancers do commonly spread from their site of origin to nearby lymph nodes and then to other organs, but cancer may also originate in the lymph nodes. This type of cancer is called lymphoma. |

17.3 Summary

- The lymphatic system is a collection of organs involved in the production, maturation, and harboring of leukocytes called lymphocytes. It also includes a network of vessels that transport or filter the fluid called lymph in which lymphocytes circulate.

- The return of lymph to the bloodstream is one of the functions of the lymphatic system. Lymph flows from tissue spaces — where it leaks out of blood vessels — to the subclavian veins in the upper chest, where it is returned to the cardiovascular system. Lymph is similar in composition to blood plasma. Its main cellular components are lymphocytes.

- Lymphatic vessels called lacteals are found in villi that line the small intestine. Lacteals absorb fatty acids from the digestion of lipids in the digestive system. The fatty acids are then transported through the network of lymphatic vessels to the bloodstream.

- The primary immune function of the lymphatic system is to protect the body against pathogens and cancerous cells. It is responsible for producing mature lymphocytes and circulating them in lymph. Lymphocytes, which include B cells and T cells, are the subset of white blood cells involved in adaptive immune responses. They may create a lasting memory of and immunity to specific pathogens.

- All lymphocytes are produced in bone marrow and then go through a process of maturation in which they “learn” to distinguish self from non-self. B cells mature in the bone marrow, and T cells mature in the thymus. Both the bone marrow and thymus are considered primary lymphatic organs.

- Secondary lymphatic organs include the tonsils, spleen, and lymph nodes. There are four pairs of tonsils that encircle the throat. The spleen filters blood, as well as lymph. There are hundreds of lymph nodes located in clusters along the lymphatic vessels. All of these secondary organs filter lymph and store lymphocytes, so they are sites where pathogens encounter and activate lymphocytes and initiate adaptive immune responses.

17.3 Review Questions

- What is the lymphatic system?

-

- Summarize the immune function of the lymphatic system.

- Explain the difference between lymphocyte maturation and lymphocyte activation.

17.3 Explore More

What is Lymphoedema or Lymphedema? Compton Care, 2016.

Spleen physiology What does the spleen do in 2 minutes, Simple Nursing, 2015.

How to check your lymph nodes, University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS FT, 2020.

Attributions

Figure 17.3.1

512px-Tonsillitis by Michaelbladon at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain). (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Kauczuk)

Figure 17.3.2

Blausen_0623_LymphaticSystem_Female by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 17.3.3

2201_Anatomy_of_the_Lymphatic_System (cropped) by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 17.3.4

1000px-Intestinal_villus_simplified.svg by Snow93 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 17.3.5

2206_The_Location_Structure_and_Histology_of_the_Thymus by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 17.3.6

Blausen_0861_Tonsils&Throat_Anatomy2 by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 17.3.7

Figure_42_02_14 by CNX OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 17.3.8

Illu_lymph_node_structure by NCI/ SEER Training on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain). (Archives: https://web.archive.org/web/20070311015818/http://training.seer.cancer.gov/module_anatomy/unit8_2_lymph_compo1_nodes.html)

Figure 17.3.9

1000px-Lymph_node_regions.svg by Fred the Oyster (derivative work) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain). (Original by NCI/ SEER Training)

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 21.2 Anatomy of the lymphatic system [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 21.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/21-1-anatomy-of-the-lymphatic-and-immune-systems

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 21.7 Location, structure, and histology of the thymus [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 21.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/21-1-anatomy-of-the-lymphatic-and-immune-systems

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014″. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436

Compton Care. (2016, March 7). What is lymphoedema or lymphedema? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RMLPwOiYnII&feature=youtu.be

OpenStax. (2016, May 27) Figure 14. The spleen is similar to a lymph node but is much larger and filters blood instead of lymph [digital image]. In Open Stax, Biology (Section 42.2). OpenStax CNX. https://cnx.org/contents/GFy_h8cu@10.8:etZobsU-@6/Adaptive-Immune-Response

Simple Nursing. (2015, June 28). Spleen physiology What does the spleen do in 2 minutes. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ah74jT00jBA&feature=youtu.be

University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS FT. (2020, May 13). How to check your lymph nodes. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L4KexZZAdyA&feature=youtu.be

A body system consisting of a network of tissues and organs that help rid the body of toxins, waste and other unwanted materials. The primary function of the lymphatic system is to transport lymph, a fluid containing infection-fighting white blood cells, throughout the body.

A fluid that leaks out of capillaries into spaces between cells and circulates in the vessels of the lymphatic system.

A hollow, tube-like structure through which blood flows in the cardiovascular system; vein, artery, or capillary.

Refers to the body system consisting of the heart, blood vessels and the blood. Blood contains oxygen and other nutrients which your body needs to survive. The body takes these essential nutrients from the blood.

The smallest type of blood vessel that connects arterioles and venules and that transfers substances between blood and tissues.

A lymphatic capillary that absorbs dietary fats in the villi of the small intestine.

A microscopic, finger-like projections in a mucous membrane that form a large surface area for absorption.

A milky fluid consisting of fat droplets and lymph. It drains from the lacteals of the small intestine into the lymphatic system during digestion.

A long, narrow, tube-like organ of the digestive system where most chemical digestion of food and virtually all absorption of nutrients take place.

A type of leukocyte produced by the lymphatic system that is a key cell in the adaptive immune response to a specific pathogen or tumor cell.

A subset of the immune system that makes tailored attacks against specific pathogens or tumor cells such as the production of antibodies that match specific antigens.

A soft connective tissue in spongy bone that produces blood cells.

An organ of the lymphatic system where lymphocytes called T cells mature.

Any organ where lymphocytes are formed and mature. They provide an environment for stem cells to divide and mature into B- and T- cells: There are two primary lymphatic organs: the red bone marrow and the thymus gland.

An organ of the lymphatic system where lymphocytes called T cells mature.

A secondary organ of the lymphatic system where blood and lymph are filtered.

One of many small structures located along lymphatic vessels where pathogens are filtered from lymph and destroyed by lymphocytes.

A set of organs which includes lymph nodes and the spleen) maintain mature naive lymphocytes and initiate an adaptive immune response.

A body fluid in humans and other animals that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. In vertebrates, it is composed of blood cells suspended in blood plasma.

a colorless cell that circulates in the blood and body fluids and is involved in counteracting foreign substances and disease; a white (blood) cell. There are several types, all amoeboid cells with a nucleus, including lymphocytes, granulocytes, monocytes, and macrophages.

A straw-yellow fluid part of blood that contains many dissolved substances and blood cells.