131 15.2 Introduction to the Digestive System

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

We All Scream for Ice Cream

If you’re an ice cream lover, then just the sight of this yummy ice cream cone may make your mouth water. The “water” in your mouth is actually saliva, a fluid released by glands that are part of the digestive system. Saliva contains digestive enzymes, among other substances important for digestion. When your mouth waters at the sight of a tasty treat, it’s a sign that your digestive system is preparing to digest food.

What Is the Digestive System?

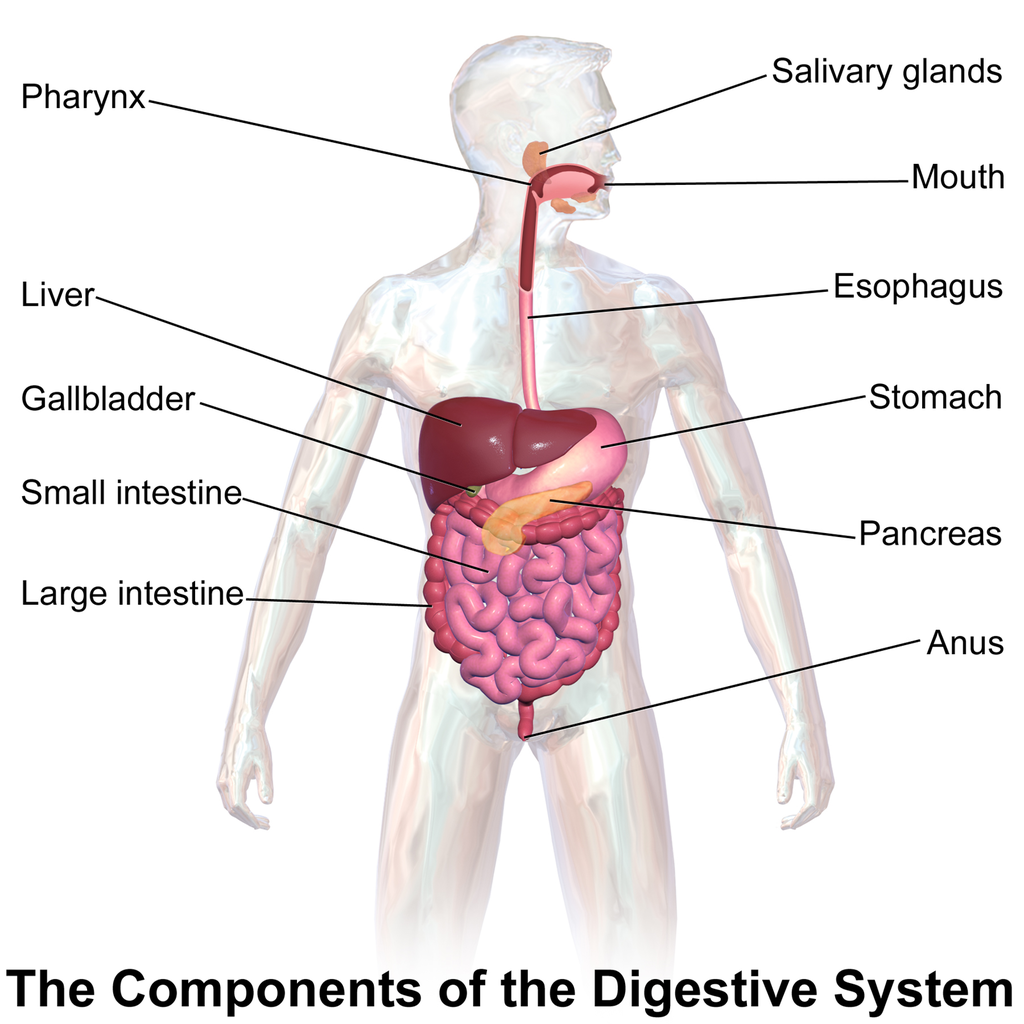

The digestive system consists of organs that break down food, absorb its nutrients, and expel any remaining waste. Organs of the digestive system are shown in Figure 15.2.2. Most of these organs make up the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, through which food actually passes. The rest of the organs of the digestive system are called accessory organs. These organs secrete enzymes and other substances into the GI tract, but food does not actually pass through them.

Functions of the Digestive System

The digestive system has three main functions relating to food: digestion of food, absorption of nutrients from food, and elimination of solid food waste. Digestion is the process of breaking down food into components the body can absorb. It consists of two types of processes: mechanical digestion and chemical digestion. Mechanical digestion is the physical breakdown of chunks of food into smaller pieces, and it takes place mainly in the mouth and stomach. Chemical digestion is the chemical breakdown of large, complex food molecules into smaller, simpler nutrient molecules that can be absorbed by body fluids (blood or lymph). This type of digestion begins in the mouth and continues in the stomach, but occurs mainly in the small intestine.

After food is digested, the resulting nutrients are absorbed. Absorption is the process in which substances pass into the bloodstream or lymph system to circulate throughout the body. Absorption of nutrients occurs mainly in the small intestine. Any remaining matter from food that is not digested and absorbed passes out of the body through the anus in the process of elimination.

Gastrointestinal Tract

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is basically a long, continuous tube that connects the mouth with the anus. If it were fully extended, it would be about nine metres long in adults. It includes the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines. Food enters the mouth, and then passes through the other organs of the GI tract, where it is digested and/or absorbed. Finally, any remaining food waste leaves the body through the anus at the end of the large intestine. It takes up to 50 hours for food or food waste to make the complete trip through the GI tract.

Tissues of the GI Tract

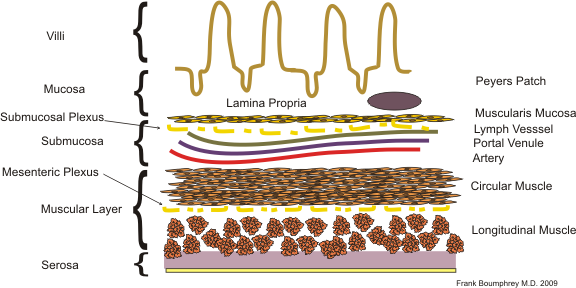

The walls of the organs of the GI tract consist of four different tissue layers, which are illustrated in Figure 15.2.3: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and serosa.

- The mucosa is the innermost layer surrounding the lumen (open space within the organs of the GI tract). This layer consists mainly of epithelium with the capacity to secrete and absorb substances. The epithelium can secret digestive enzymes and mucus, and it can absorb nutrients and water.

- The submucosa layer consists of connective tissue that contains blood and lymph vessels, as well as nerves. The vessels are needed to absorb and carry away nutrients after food is digested, and nerves help control the muscles of the GI tract organs.

- The muscularis externa layer contains two types of smooth muscle: longitudinal muscle and circular muscle. Longitudinal muscle runs the length of the GI tract organs, and circular muscle encircles the organs. Both types of muscles contract to keep food moving through the tract by the process of peristalsis, which is described below.

- The serosa layer is the outermost layer of the walls of GI tract organs. This is a thin layer that consists of connective tissue and separates the organs from surrounding cavities and tissues.

|

|

Peristalisis in the GI Tract

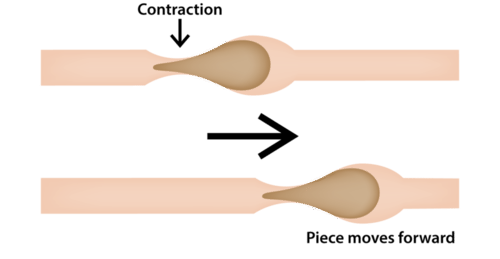

The muscles in the walls of GI tract organs enable peristalsis, which is illustrated in Figure 15.2.5. Peristalsis is a continuous sequence of involuntary muscle contraction and relaxation that moves rapidly along an organ like a wave, similar to the way a wave moves through a spring toy. Peristalsis in organs of the GI tract propels food through the tract.

Watch the video “What is peristalsis?” by Mister Science to see peristalsis in action:

What is peristalsis?, Mister Science, 2018.

Immune Function of the GI Tract

The GI tract plays an important role in protecting the body from pathogens. The surface area of the GI tract is estimated to be about 32 square metres (105 square feet), or about half the area of a badminton court. This is more than three times the area of the exposed skin of the body, and it provides a lot of area for pathogens to invade the tissues of the body. The innermost mucosal layer of the walls of the GI tract provides a barrier to pathogens so they are less likely to enter the blood or lymph circulations. The mucus produced by the mucosal layer, for example, contains antibodies that mark many pathogenic microorganisms for destruction. Enzymes in some of the secretions of the GI tract also destroy pathogens. In addition, stomach acids have a very low pH that is fatal for many microorganisms that enter the stomach.

Divisions of the GI Tract

The GI tract is often divided into an upper GI tract and a lower GI tract. For medical purposes, the upper GI tract is typically considered to include all the organs from the mouth through the first part of the small intestine, called the duodenum. For our instructional purposes, it makes more sense to include the mouth through the stomach in the upper GI tract, and all of the small intestine — as well as the large intestine — in the lower GI tract.

Upper GI Tract

The mouth is the first digestive organ that food enters. The sight, smell, or taste of food stimulates the release of digestive enzymes and other secretions by salivary glands inside the mouth. The major salivary gland enzyme is amylase. It begins the chemical digestion of carbohydrates by breaking down starches into sugar. The mouth also begins the mechanical digestion of food. When you chew, your teeth break, crush, and grind food into increasingly smaller pieces. Your tongue helps mix the food with saliva and also helps you swallow.

A lump of swallowed food is called a bolus. The bolus passes from the mouth into the pharynx, and from the pharynx into the esophagus. The esophagus is a long, narrow tube that carries food from the pharynx to the stomach. It has no other digestive functions. Peristalsis starts at the top of the esophagus when food is swallowed and continues down the esophagus in a single wave, pushing the bolus of food ahead of it.

From the esophagus, food passes into the stomach, where both mechanical and chemical digestion continue. The muscular walls of the stomach churn and mix the food, thus completing mechanical digestion, as well as mixing the food with digestive fluids secreted by the stomach. One of these fluids is hydrochloric acid (HCl). In addition to killing pathogens in food, it gives the stomach the low pH needed by digestive enzymes that work in the stomach. One of these enzymes is pepsin, which chemically digests proteins. The stomach stores the partially digested food until the small intestine is ready to receive it. Food that enters the small intestine from the stomach is in the form of a thick slurry (semi-liquid) called chyme.

Lower GI Tract

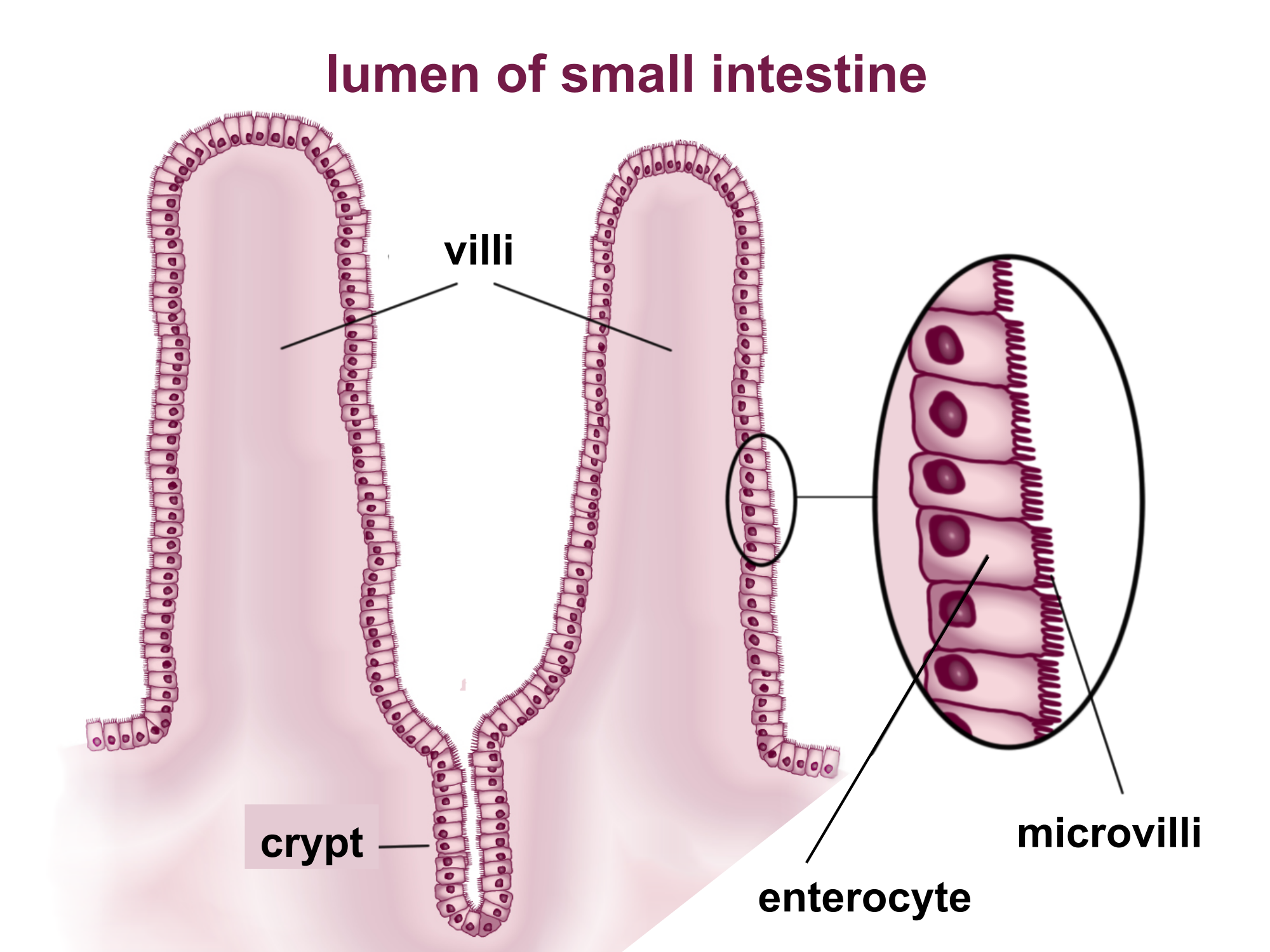

The small intestine is a narrow, but very long tubular organ. It may be almost seven metres long in adults. It is the site of most chemical digestion and virtually all absorption of nutrients. Many digestive enzymes are active in the small intestine, some of which are produced by the small intestine itself, and some of which are produced by the pancreas, an accessory organ of the digestive system. Much of the inner lining of the small intestine is covered by tiny finger-like projections called villi, each of which is covered by even tinier projections called microvilli. These projections, shown in the drawing below (Figure 15.2.6), greatly increase the surface area through which nutrients can be absorbed from the small intestine.

From the small intestine, any remaining nutrients and food waste pass into the large intestine. The large intestine is another tubular organ, but it is wider and shorter than the small intestine. It connects the small intestine and the anus. Waste that enters the large intestine is in a liquid state. As it passes through the large intestine, excess water is absorbed from it. The remaining solid waste — called feces — is eventually eliminated from the body through the anus.

Accessory Organs of the Digestive System

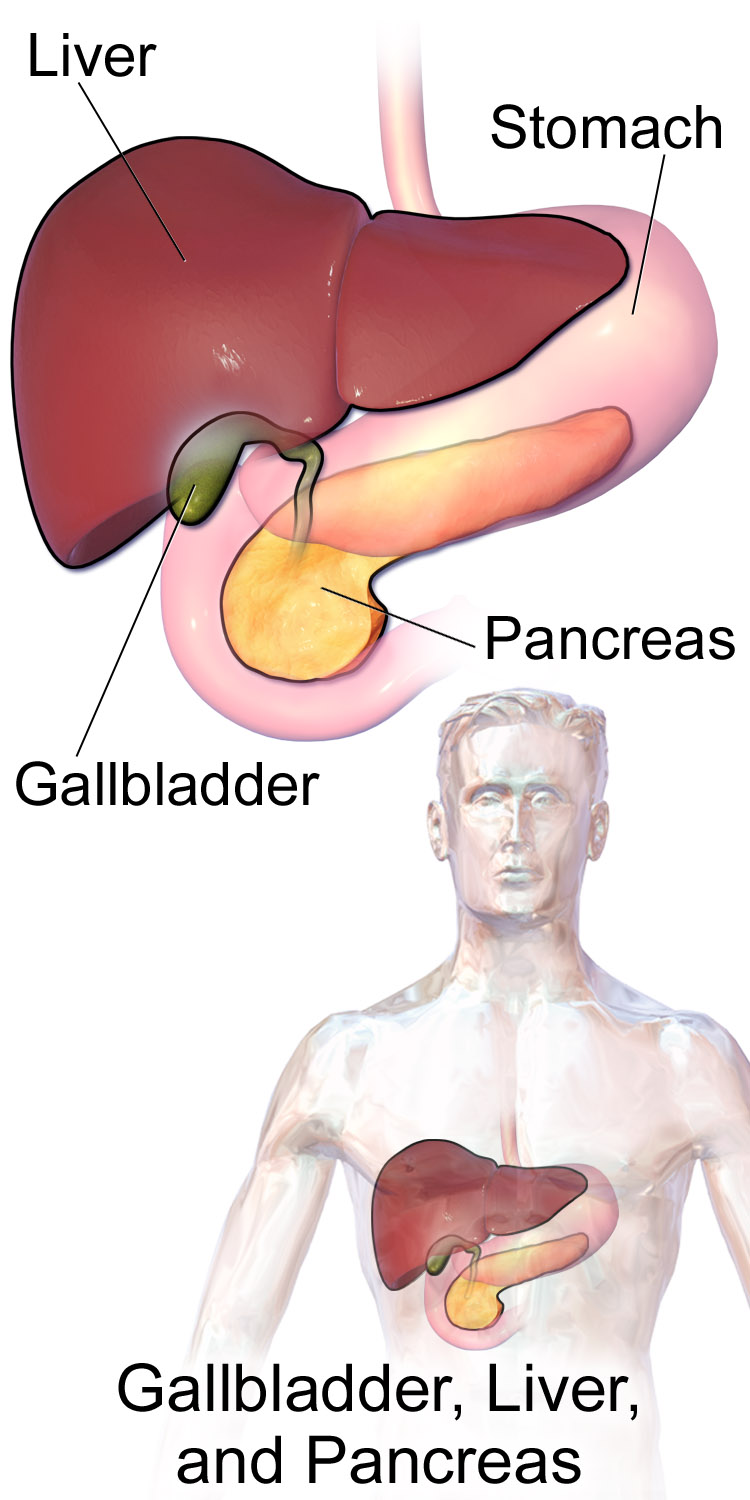

Accessory organs of the digestive system are not part of the GI tract, so they are not sites where digestion or absorption take place. Instead, these organs secrete or store substances needed for the chemical digestion of food. The accessory organs include the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. They are shown in Figure 15.2.7 and described in the text that follows.

- The liver is an organ with multitude of functions. Its main digestive function is producing and secreting a fluid called bile, which reaches the small intestine through a duct. Bile breaks down large globules of lipids into smaller ones that are easier for enzymes to chemically digest. Bile is also needed to reduce the acidity of food entering the small intestine from the highly acidic stomach, because enzymes in the small intestine require a less acidic environment in order to work.

- The gallbladder is a small sac below the liver that stores some of the bile from the liver. The gallbladder also concentrates the bile by removing some of the water from it. It then secretes the concentrated bile into the small intestine as needed for fat digestion following a meal.

- The pancreas secretes many digestive enzymes, and releases them into the small intestine for the chemical digestion of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids. The pancreas also helps lessen the acidity of the small intestine by secreting bicarbonate, a basic substance that neutralizes acid.

15.2 Summary

- The digestive system consists of organs that break down food, absorb its nutrients, and expel any remaining food waste.

- Digestion is the process of breaking down food into components that the body can absorb. It includes mechanical digestion and chemical digestion. Absorption is the process of taking up nutrients from food by body fluids for circulation to the rest of the body. Elimination is the process of excreting any remaining food waste after digestion and absorption are finished.

- Most digestive organs form a long, continuous tube called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. It starts at the mouth, which is followed by the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. The upper GI tract consists of the mouth through the stomach, while the lower GI tract consists of the small and large intestines.

- Digestion and/or absorption take place in most of the organs of the GI tract. Organs of the GI tract have walls that consist of several tissue layers that enable them to carry out these functions. The inner mucosa has cells that secrete digestive enzymes and other digestive substances, as well as cells that absorb nutrients. The muscle layer of the organs enables them to contract and relax in waves of peristalsis to move food through the GI tract.

- Three digestive organs — the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas — are accessory organs of digestion. They secrete substances needed for chemical digestion into the small intestine.

15.2 Review Questions

- What is the digestive system?

- What are the three main functions of the digestive system? Define each function.

-

- Relate the tissues in the walls of GI tract organs to the functions the organs perform.

15.2 Explore More

How your digestive system works – Emma Bryce, TED-Ed, 2017.

How does your body know you’re full? – Hilary Coller, TED-Ed, 2017.

Attributions

Figure 15.2.1

Ice Cream [photo] by Mark Cruz on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 15.2.2

Blausen_0316_DigestiveSystem by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 15.2.3

Intestinal_layers by Boumphreyfr on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

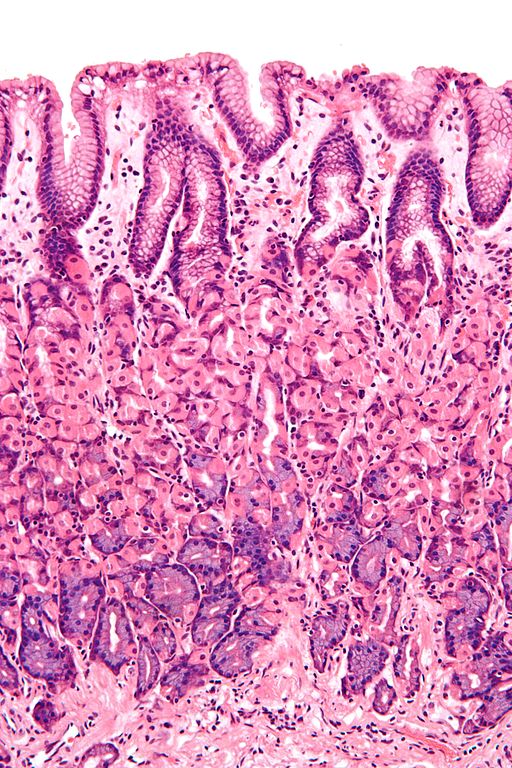

Figure 15.2.4

512px-Normal_gastric_mucosa_intermed_mag by Nephron on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 15.2.5

Peristalsis pushes food through the GI tract by CK-12 Foundation is used under a CC BY NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

Figure 15.2.6

Villi_&_microvilli_of_small_intestine.svg by BallenaBlanca on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 15.2.7

Blausen_0428_Gallbladder-Liver-Pancreas_Location by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

References

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Brainard, J/ CK-12 Foundation. (2016). Figure 4 Peristalsis pushes food through the GI tract. [digital image]. In CK-12 College Human Biology (Section 17.2) [online Flexbook]. CK12.org. https://www.ck12.org/book/ck-12-college-human-biology/section/17.2/

Mister Science. (2018). What is peristalsis? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCxTlkZfjArUobBAeVwzJjYg/videos

TED-Ed. (2017, November 13). How does your body know you’re full? – Hilary Coller. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YVfyYrEmzgM&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2017, December 14). How your digestive system works – Emma Bryce. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Og5xAdC8EUI&feature=youtu.be

A body system including a series of hollow organs joined in a long, twisting tube from the mouth to the anus. The hollow organs that make up the GI tract are the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. The liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are the solid organs of the digestive system.

The process of breaking down food into nutrients that can be absorbed by blood or lymph.

The physical breakdown of chunks of food into smaller pieces by organs of the digestive system, for example chewing food.

Chemical breakdown of large, complex food molecules into smaller, simpler nutrient molecules that can be absorbed by blood or lymph. Usually involves a digestive enzyme.

A body fluid in humans and other animals that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. In vertebrates, it is composed of blood cells suspended in blood plasma.

A fluid that leaks out of capillaries into spaces between cells and circulates in the vessels of the lymphatic system.

Process in which substances such as nutrients pass into the blood or lymph.

The process in which wastes pass out of the body.

The organs of the digestive system through which food passes during digestion, including the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines.

The opening in the lower part of the human face, surrounded by the lips, through which food is taken in and from which speech and other sounds are emitted.

The final part of the large intestine with an opening to the outside for feces to pass through.

Tubular organ that connects the mouth and nasal cavity with the larynx and through which air and food pass.

A long, narrow, tube-like digestive organ through which food passes from the pharynx to the stomach.

A sac-like organ of the digestive system between the esophagus and small intestine in which both mechanical and chemical digestion take place.

A long, narrow, tube-like organ of the digestive system where most chemical digestion of food and virtually all absorption of nutrients take place.

An organ of the digestive system that removes water and salts from food waste and forms solid feces for elimination.

The innermost tunic of the wall. It lines the lumen of the digestive tract. The mucosa consists of epithelium, an underlying loose connective tissue layer called lamina propria, and a thin layer of smooth muscle called the muscularis mucosa.

The layer of dense, irregular connective tissue or loose connective tissue that supports the mucosa, as well as joins the mucosa to the bulk of underlying smooth muscle (fibers that run circularly within a layer of longitudinal muscle).

Consists of smooth muscle in most of the digestive tract, but is striated muscle in the upper part of the esophagus. Along most of the tract the externa consists of an inner circular and outer longitudinal layer.

A smooth membrane that consists of a thin connective tissue layer and a thin layer of cells that secrete serous fluid.

A distinctive pattern of smooth muscle contractions that propels foodstuffs distally through the esophagus and intestines.

A microorganism which causes disease.

A slimy substance produced by mucous membranes that traps pathogens, particles, and debris.

An antibody, also known as an immunoglobulin, is a large, Y-shaped protein produced mainly by plasma cells that is used by the immune system to neutralize pathogens such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses.

Biological molecules that lower amount the energy required for a reaction to occur.

A measure of the acidity or basicity of aqueous or other liquid solutions. The term translates the values of the concentration of the hydrogen ion in a scale ranging from 0 and 14. In pure water, which is neutral (neither acidic nor alkaline), the concentration of the hydrogen ion corresponds to a pH of 7. A solution with a pH less than 7 is considered acidic; a solution with a pH greater than 7 is considered basic, or alkaline.

The part of the gastrointestinal tract that includes the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, and stomach.

The part of the GI tract that includes the small and large intestines.

The first and shortest of three parts of the small intestine where most chemical digestion occurs.

One of many exocrine glands in the mouth that secrete saliva into the mouth through ducts.

An enzyme, found chiefly in saliva and pancreatic fluid, that converts starch and glycogen into simple sugars.

A biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1. Complex carbohydrates are polymers made from monomers of simple carbohydrates, also termed monosaccharides.

A stored form of glucose used by plants.

The generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. The various types of sugar are derived from different sources. Simple sugars are called monosaccharides and include glucose, fructose, and galactose.

A lump of swallowed food.

The chief digestive enzyme in the stomach, which breaks down proteins into polypeptides.

A thick, semi-liquid mixture that food in the gastrointestinal tract becomes by the time it leaves the stomach.

A long, flat gland that sits tucked behind the stomach in the upper abdomen. The pancreas produces enzymes that help digestion and hormones that help regulate the way your body processes sugar (glucose).

A microscopic, finger-like projections in a mucous membrane that form a large surface area for absorption.

One of many tiny projections covering each villus in the mucosal lining the small intestine that increases its absorptive surface.

An organ of digestion and excretion that secretes bile for lipid digestion and breaks down excess amino acids and toxins in the blood.

A sac-like organ that stores bile from the liver and secretes it into the duodenum of the small intestine as needed for digestion.