55 9.3 Creating an Organizational Structure

Learning Objectives

- Know and be able to differentiate among the four types of organizational structure.

- Understand why a change in structure may be needed.

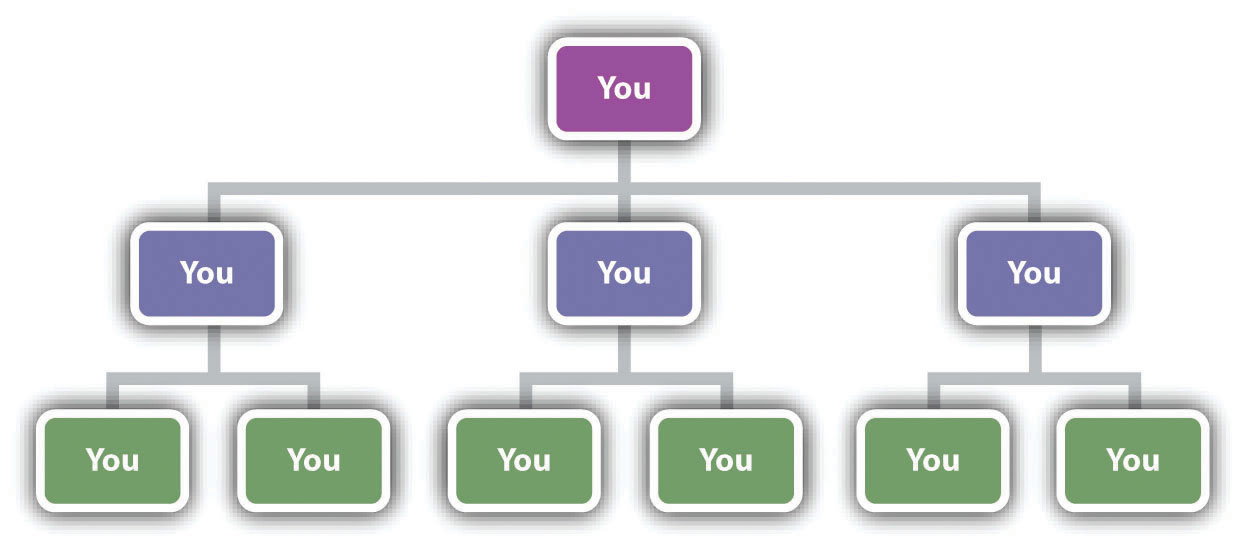

Within most firms, executives rely on vertical and horizontal linkages to create a structure that they hope will match the needs of their firm’s strategy. Four types of structures are available to executives: (1) simple, (2) functional, (3) multidivisional, and (4) matrix (Table 9.3 “Common Organizational Structures”). Like snowflakes, however, no two organizational structures are exactly alike. When creating a structure for their firm, executives will take one of these types and adapt it to fit the firm’s unique circumstances. As they do this, executives must realize that the choice of structure will influences their firm’s strategy in the future. Once a structure is created, it constrains future strategic moves. If a firm’s structure is designed to maximize efficiency, for example, the firm may lack the flexibility needed to react quickly to exploit new opportunities.

Table 9.3 Common Organizational Structures

Executives rely on vertical and horizontal linkages to create a structure that they hope will match the firm’s needs. While no two organizational structures are exactly alike, four general types of structures are available to executives: simple functional, multidivisional, and matrix.

| Simple Strucutre | Simple structures do not rely on formal systems of division of labor, and organizational charts are not generally needed. If the firm is a sole proprietorship, one person performs all of the tasks that the organization needs to accomplish. Consequently, this structure is common for many small businesses. |

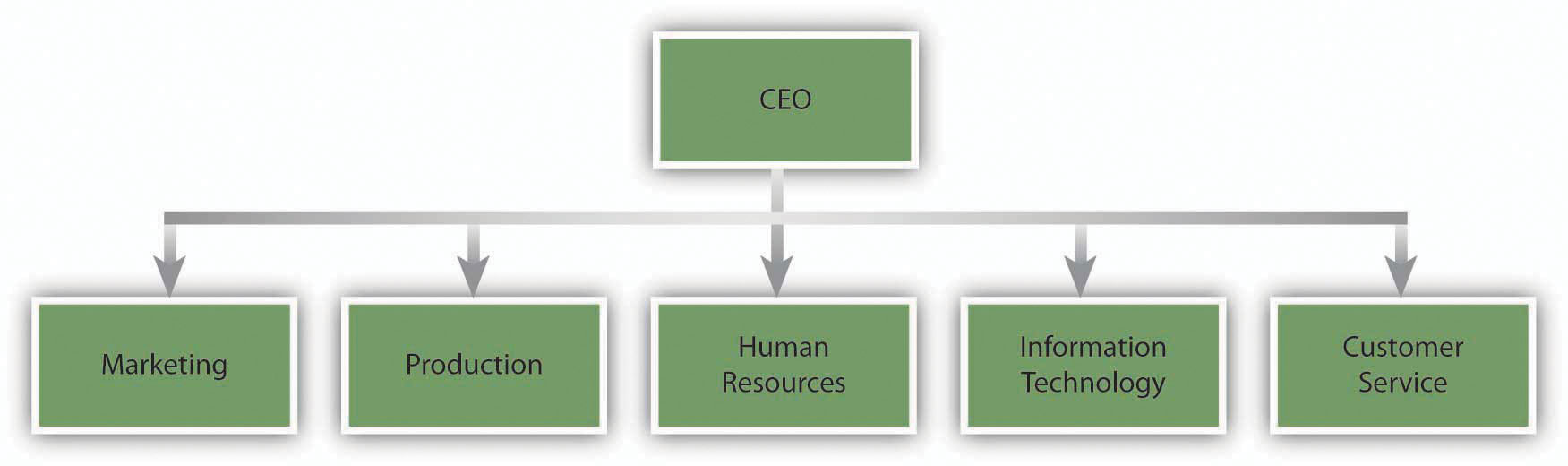

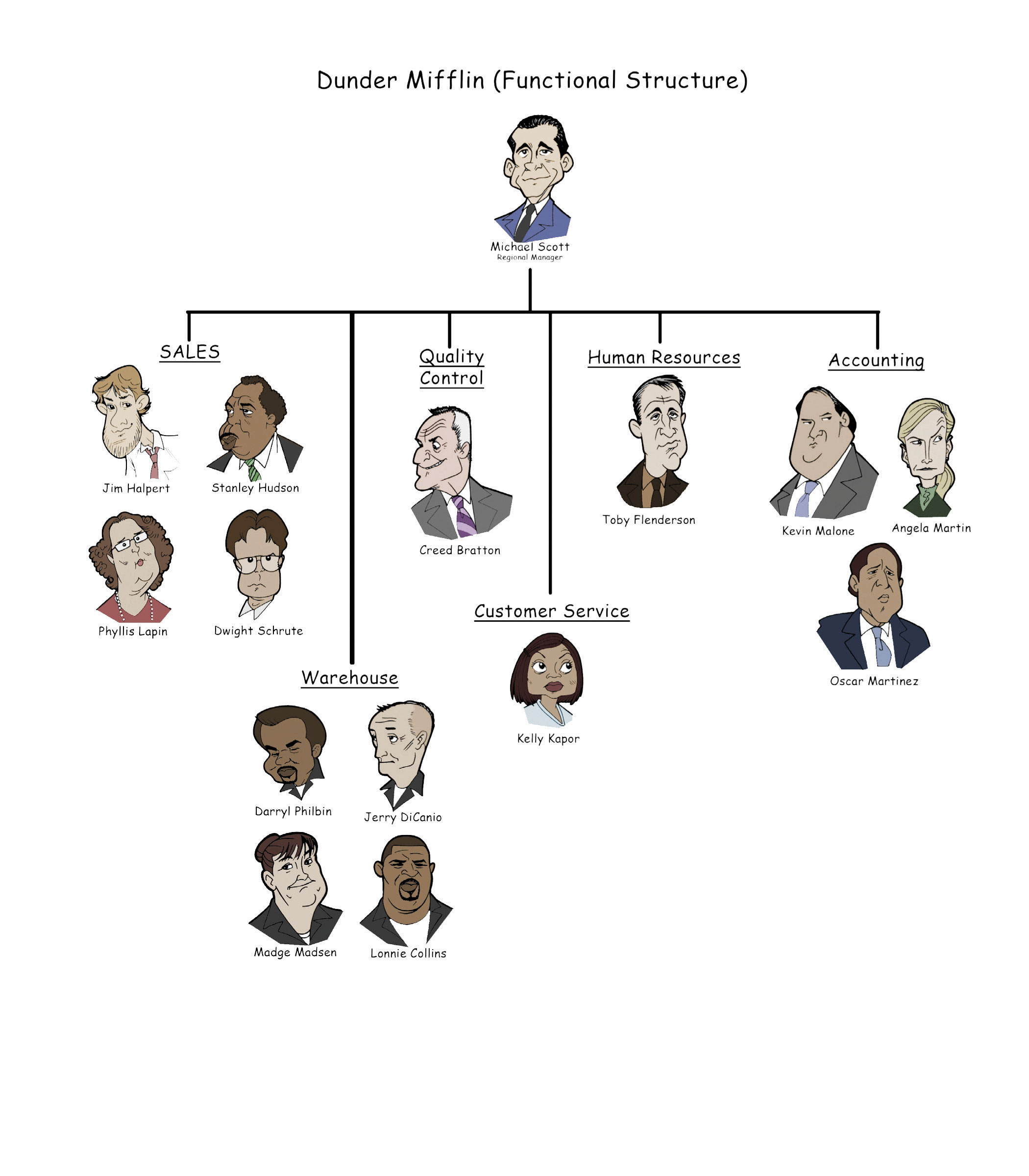

| Functional Structure | Within a functional structure, employees are divided into departments that each handles activities related to a functional area of the business, such as marketing, production, human resources, information technology, and customer service. |

| Multidivisional Structure | In this type of structure, employees are divided into departments based on product areas and/or geographic regions. General Electric, for example, has six product divisions: Energy, Capital, Home & Business Solutions, Healthcare, Aviation, and Transportation. |

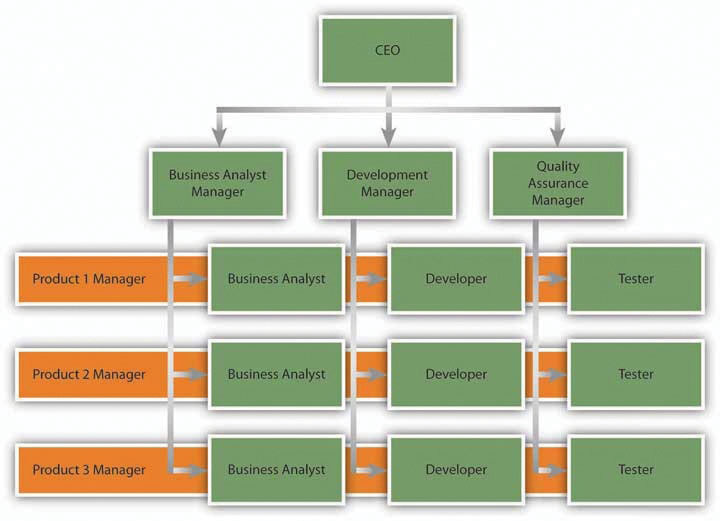

| Matrix Structure | Firms that engage in projects of limited duration often use a matrix structure where employees can be put on different teams to maximize creativity and idea flow. As parodied in the move Office Space, this structure is common in high tech and engineering firms. |

Simple Structure

Many organizations start out with a simple structure. In this type of structure, an organizational chart is usually not needed. Simple structures do not rely on formal systems of division of labor (Table 9.4 “Simple Structure”). If the firm is a sole proprietorship, one person performs all the tasks the organization needs to accomplish. For example, on the TV series The Simpsons, both bar owner Moe Szyslak and the Comic Book Guy are shown handling all aspects of their respective businesses.

Table 9.4 Simple Structure

Most small businesses begin with a simple structure where one person or a small set of people share the tasks needed to accomplish the firm’s goals with relatively little formalized division of labor. We illustrate a number of businesses that commonly rely upon a simple structure below.

| Need a few dollars to tide you over? You may want to pawn your rare coin collection. The pawn shop’s simple structure will mean that the same person values your coins, decides how much money you can borrow, and writes up your paperwork. | The reality show Miami Ink illustrates how a tattoo parlor’s simple structure governs a colorful set of tattoo artists who create body art for their patrons. |

| Architects often also act as marketers and accountants when drafting their small business plans. | Bait shop owners generally do not dive deep into their pockets to pay for additional personnel as many are owner operated. |

| When a dry cleaner is family owned as many are, all members of the family pitch in as needed to clean clothing and wait on customers. | There is flexibility in the management of many yoga studios given the laid back management style often embraced. |

|

Instrument dealers may create beautiful music, but they rarely create complex organizational structures. |

“Bridezillas” are an occupational hazard for bridal shops, but these shops are generally able to avoid the complexity associated with other organizational structures. |

If the firm consists of more than one person, tasks tend to be distributed among them in an informal manner rather than each person developing a narrow area of specialization. In a family-run restaurant or bed and breakfast, for example, each person must contribute as needed to tasks, such as cleaning restrooms, food preparation, and serving guests (hopefully not in that order). Meanwhile, strategic decision making in a simple structure tends to be highly centralized. Indeed, often the owner of the firm makes all the important decisions. Because there is little emphasis on hierarchy within a simple structure, organizations that use this type of structure tend to have very few rules and regulations. The process of evaluating and rewarding employees’ performance also tends to be informal.

The informality of simple structures creates both advantages and disadvantages. On the plus side, the flexibility offered by simple structures encourages employees’ creativity and individualism. Informality has potential negative aspects, too. Important tasks may be ignored if no one person is specifically assigned accountability for them. A lack of clear guidance from the top of the organization can create confusion for employees, undermine their motivation, and make them dissatisfied with their jobs. Thus when relying on a simple structure, the owner of a firm must be sure to communicate often and openly with employees.

Functional Structure

As a small organization grows, the person in charge of it often finds that a simple structure is no longer adequate to meet the organization’s needs. Organizations become more complex as they grow, and this can require more formal division of labor and a strong emphasis on hierarchy and vertical links. In many cases, these firms evolve from using a simple structure to relying on a functional structure.

Table 9.5 Functional Structure

Functional structures rely on a division of labor whereby groups of people handle activities related to a specific function of the overall business. We illustrate functional structures in action within two types of organizations that commonly use them.

| Grocery Store Functions | Spa Functions |

| Grocery stockers often work at night to make sure shelves stay full during the day. | Some spa employees manicure fingernails, a practice that is over four thousand years old. Many also provide pedicures, a service whose popularity has nearly doubled in the past decade. |

| Pharmacists’ specialized training allows them to command pay that can exceed $50 an hour. | Compared to other spa functions, little training is required of a tanning bed operator–although the ability to tell time may help. |

| Bakers wake up early to give shoppers their daily bread. | Almost anyone can buy a shotgun or parent a child without any training, but every state requires a license in order to cut hair. |

| Bagging groceries requires a friendly personality as well as knowing that eggs should not go on the bottom. | Cucumber masks are usually applied by a skin care specialist who has taken a professional training program. |

| Folks that work checkout aisles should be trusted to handle cash. | The license required of massage therapists in many states ensures that spa visits end happily. |

|

The creation of produce, deli, and butcher departments provides an efficient way to divide a grocery store physically as well as functionally. |

Within a functional structure, employees are divided into departments that each handle activities related to a functional area of the business, such as marketing, production, human resources, information technology, and customer service (Table 9.5 “Functional Structure”). Each of these five areas would be headed up by a manager who coordinates all activities related to her functional area. Everyone in a company that works on marketing the company’s products, for example, would report to the manager of the marketing department. The marketing managers and the managers in charge of the other four areas in turn would report to the chief executive officer.

Using a functional structure creates advantages and disadvantages. An important benefit of adopting a functional structure is that each person tends to learn a great deal about his or her particular function. By being placed in a department that consists entirely of marketing professionals, an individual has a great opportunity to become an expert in marketing. Thus a functional structure tends to create highly skilled specialists. Second, grouping everyone that serves a particular function into one department tends to keep costs low and to create efficiency. Also, because all the people in a particular department share the same background training, they tend to get along with one another. In other words, conflicts within departments are relatively rare.

Using a functional structure also has a significant downside: executing strategic changes can be very slow when compared with other structures. Suppose, for example, that a textbook publisher decides to introduce a new form of textbook that includes “scratch and sniff” photos that let students smell various products in addition to reading about them. If the publisher relies on a simple structure, the leader of the firm can simply assign someone to shepherd this unique new product through all aspects of the publication process.

If the publisher is organized using a functional structure, however, every department in the organization will have to be intimately involved in the creation of the new textbooks. Because the new product lies outside each department’s routines, it may become lost in the proverbial shuffle. And unfortunately for the books’ authors, the publication process will be halted whenever a functional area does not live up to its responsibilities in a timely manner. More generally, because functional structures are slow to execute change, they tend to work best for organizations that offer narrow and stable product lines.

The specific functional departments that appear in an organizational chart vary across organizations that use functional structures. In the example offered earlier in this section, a firm was divided into five functional areas: (1) marketing, (2) production, (3) human resources, (4) information technology, and (5) customer service. In the TV show The Office, a different approach to a functional structure is used at the Scranton, Pennsylvania, branch of Dunder Mifflin. As of 2009, the branch was divided into six functional areas: (1) sales, (2) warehouse, (3) quality control, (4) customer service, (5) human resources, and (6) accounting. A functional structure was a good fit for the branch at the time because its product line was limited to just selling office paper.

Multidivisional Structure

Many organizations offer a wide variety of products and services. Some of these organizations sell their offerings across an array of geographic regions. These approaches require firms to be very responsive to customers’ needs. Yet, as noted, functional structures tend to be fairly slow to change. As a result, many firms abandon the use of a functional structure as their offerings expand. Often the new choice is a multidivisional structure. In this type of structure, employees are divided into departments based on product areas and/or geographic regions.

General Electric (GE) is an example of a company organized this way. As shown in the organization chart that accompanies this chapter’s opening vignette, most of the company’s employees belong to one of six product divisions (Energy, Capital, Home & Business Solutions, Health Care, Aviation, and Transportation) or to a division that is devoted to all GE’s operations outside the United States (Global Growth & Operations).

A big advantage of a multidivisional structure is that it allows a firm to act quickly. When GE makes a strategic move such as acquiring the well-support division of John Wood Group PLC, only the relevant division (in this case, Energy) needs to be involved in integrating the new unit into GE’s hierarchy. In contrast, if GE was organized using a functional structure, the transition would be much slower because all the divisions in the company would need to be involved. A multidivisional structure also helps an organization to better serve customers’ needs. In the summer of 2011, for example, GE’s Capital division started to make real-estate loans after exiting that market during the financial crisis of the late 2000s (Jacobius, 2011). Because one division of GE handles all the firm’s loans, the wisdom and skill needed to decide when to reenter real-estate lending was easily accessible.

Of course, empowering divisions to act quickly can backfire if people in those divisions take actions that do not fit with the company’s overall strategy. McDonald’s experienced this kind of situation in 2002. In particular, the French division of McDonald’s ran a surprising advertisement in a magazine called Femme Actuelle. The ad included a quote from a nutritionist that asserted children should not eat at a McDonald’s more than once per week. Executives at McDonald’s headquarters in suburban Chicago were concerned about the message sent to their customers, of course, and they made it clear that they strongly disagreed with the nutritionist.

Problems can be created when delegating lots of authority to local divisions. McDonald’s top executives were angered when an ad by their French division suggested that children should only eat at their restaurants once a week.

Alfonsina Blyde – Everything to see you smile – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Another downside of multidivisional structures is that they tend to be more costly to operate than functional structures. While a functional structure offers the opportunity to gain efficiency by having just one department handle all activities in an area, such as marketing, a firm using a multidivisional structure needs to have marketing units within each of its divisions. In GE’s case, for example, each of its seven divisions must develop marketing skills. Absorbing the extra expenses that are created reduces a firm’s profit margin.

GE’s organizational chart highlights a way that firms can reduce some of these expenses: the centralization of some functional services. As shown in the organizational chart, departments devoted to important aspects of public relations, business development, legal, global research, human resources, and finance are maintained centrally to provide services to the six product divisions and the geographic division. By consolidating some human resource activities in one location, for example, GE creates efficiency and saves money.

An additional benefit of such moves is that consistency is created across divisions. In 2011, for example, the Coca-Cola Company created an Office of Sustainability to coordinate sustainability initiatives across the entire company. Bea Perez was named Coca-Cola’s chief sustainability officer and was put in charge of the Office of Sustainability. At the time, Coca-Cola’s chief executive officer Muhtar Kent noted that Coca-Cola had “made significant progress with our sustainability initiatives, but our current approach needs focus and better integration (McWilliams, 2011).” In other words, a department devoted to creating consistency across Coca-Cola’s sustainability efforts was needed for Coca-Cola to meet its sustainability goals.

Matrix Structure

Within functional and multidivisional structures, vertical linkages between bosses and subordinates are the most elements. Matrix structures, in contrast, rely heavily on horizontal relationships (Ketchen & Short, 2011). In particular, these structures create cross-functional teams that each work on a different project. This offers several benefits: maximizing the organization’s flexibility, enhancing communication across functional lines, and creating a spirit of teamwork and collaboration. A matrix structure can also help develop new managers. In particular, a person without managerial experience can be put in charge of a relatively small project as a test to see whether the person has a talent for leading others.

Using a matrix structure can create difficulties too. One concern is that using a matrix structure violates the unity of command principle because each employee is assigned multiple bosses. Specifically, any given individual reports to a functional area supervisor as well as one or more project supervisors. This creates confusion for employees because they are left unsure about who should be giving them direction. Violating the unity of command principle also creates opportunities for unsavory employees to avoid responsibility by claiming to each supervisor that a different supervisor is currently depending on their efforts.

The potential for conflicts arising between project managers within a matrix structure is another concern. Chances are that you have had some classes with professors who are excellent speakers while you have been forced to suffer through a semester of incomprehensible lectures in other classes. This mix of experiences reflects a fundamental reality of management: in any organization, some workers are more talented and motivated than others. Within a matrix structure, each project manager naturally will want the best people in the company assigned to her project because their boss evaluates these managers based on how well their projects perform. Because the best people are a scarce resource, infighting and politics can easily flare up around which people are assigned to each project.

Given these problems, not every organization is a good candidate to use a matrix structure. Organizations such as engineering and consulting firms that need to maximize their flexibility to service projects of limited duration can benefit from the use of a matrix. Matrix structures are also used to organize research and development departments within many large corporations. In each of these settings, the benefits of organizing around teams are so great that they often outweigh the risks of doing so.

Strategy at the Movies

Office Space

How much work can a man accomplish with eight bosses breathing down his neck? For Peter Gibbons, an employee at information technology firm Initech in the 1999 movie Office Space, the answer was zero. Initech’s use of a matrix structure meant that each employee had multiple bosses, each representing a different aspect of Initech’s business. High-tech firms often use matrix to gain the flexibility needed to manage multiple projects simultaneously. Successfully using a matrix structure requires excellent communication among various managers—however, excellence that Initech could not reach. When Gibbons forgot to put the appropriate cover sheet on his TPS report, each of his eight bosses—and a parade of his coworkers—admonished him. This fiasco and others led to Gibbons to become cynical about his job.

Simpler organizational structures can be equally frustrating. Joanna, a waitress at nearby restaurant Chotchkie’s, had only one manager—a stark contrast to Gibbons’s eight bosses. Unfortunately, Joanna’s manager had an unhealthy obsession with the “flair” (colorful buttons and pins) used by employees to enliven their uniforms. A series of mixed messages about the restaurant’s policy on flair led Joanna to emphatically proclaim—both verbally and nonverbally—her disdain for the manager. She then quit her job and stormed out of the restaurant.

Office Space illustrates the importance of organizational design decisions to an organization’s culture and to employees’ motivation levels. A matrix structure can facilitate resource sharing and collaboration but may also create complicated working relationships and impose excessive stress on employees. Chotchkie’s organizational structure involved simpler working relationships, but these relationships were strained beyond the breaking point by a manager’s eccentricities. In a more general sense, Office Space shows that all organizational structures involve a series of trade-offs that must be carefully managed.

Within a poorly organized firm like Initech, simply keeping possession of a treasured stapler is a challenge.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Boundaryless Organizations

Most organizational charts show clear divisions and boundaries between different units. The value of a much different approach was highlighted by former GE CEO Jack Welch when he created the term boundaryless organization. A boundaryless organization is one that removes the usual barriers between parts of the organization as well as barriers between the organization and others (Askenas, et. al., 1995). Eliminating all internal and external barriers is not possible, of course, but making progress toward being boundaryless can help an organization become more flexible and responsive. One example is W.L. Gore, a maker of fabrics, medical implants, industrial sealants, filtration systems, and consumer products. This firm avoids organizational charts, management layers, and supervisors despite having approximately nine thousand employees across thirty countries. Rather than granting formal titles to certain people, leaders with W.L. Gore emerge based on performance and they attract followers to their ideas over time. As one employee noted, “We vote with our feet. If you call a meeting, and people show up, you’re a leader (Hamel, 2007).”

The boundaryless approach to structure embraced by W.L. Gore drives the kind of creative thinking that led to their most famous product, GORE-TEX.

Adifansnet – adidas_Men’s_WINTER STORY – CC BY-SA 2.0.

An illustration of how removing barriers can be valuable has its roots in a very unfortunate event. During 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, rescue efforts were hampered by a lack of coordination between responders from the National Guard (who are controlled by state governments) and from active-duty military units (who are controlled by federal authorities). According to one National Guard officer, “It was just like a solid wall was between the two entities (Elliott, 2011).” Efforts were needlessly duplicated in some geographic areas while attention to other areas was delayed or inadequate. For example, poor coordination caused the evacuation of thousands of people from the New Orleans Superdome to be delayed by a full day. The results were immense human suffering and numerous fatalities.

In 2005, boundaries between organizations hampered rescue efforts following Hurricane Katrina.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

To avoid similar problems from arising in the future, barriers between the National Guard and active-duty military units are being bridged by special military officers called dual-status commanders. These individuals will be empowered to lead both types of units during a disaster recovery effort, helping to ensure that all areas receive the attention they need in a timely manner.

Reasons for Changing an Organization’s Structure

Creating an organizational structure is not a onetime activity. Executives must revisit an organization’s structure over time and make changes to it if certain danger signs arise. For example, a structure might need to be adjusted if decisions with the organization are being made too slowly or if the organization is performing poorly. Both these problems plagued Sears Holdings in 2008, leading executives to reorganize the company.

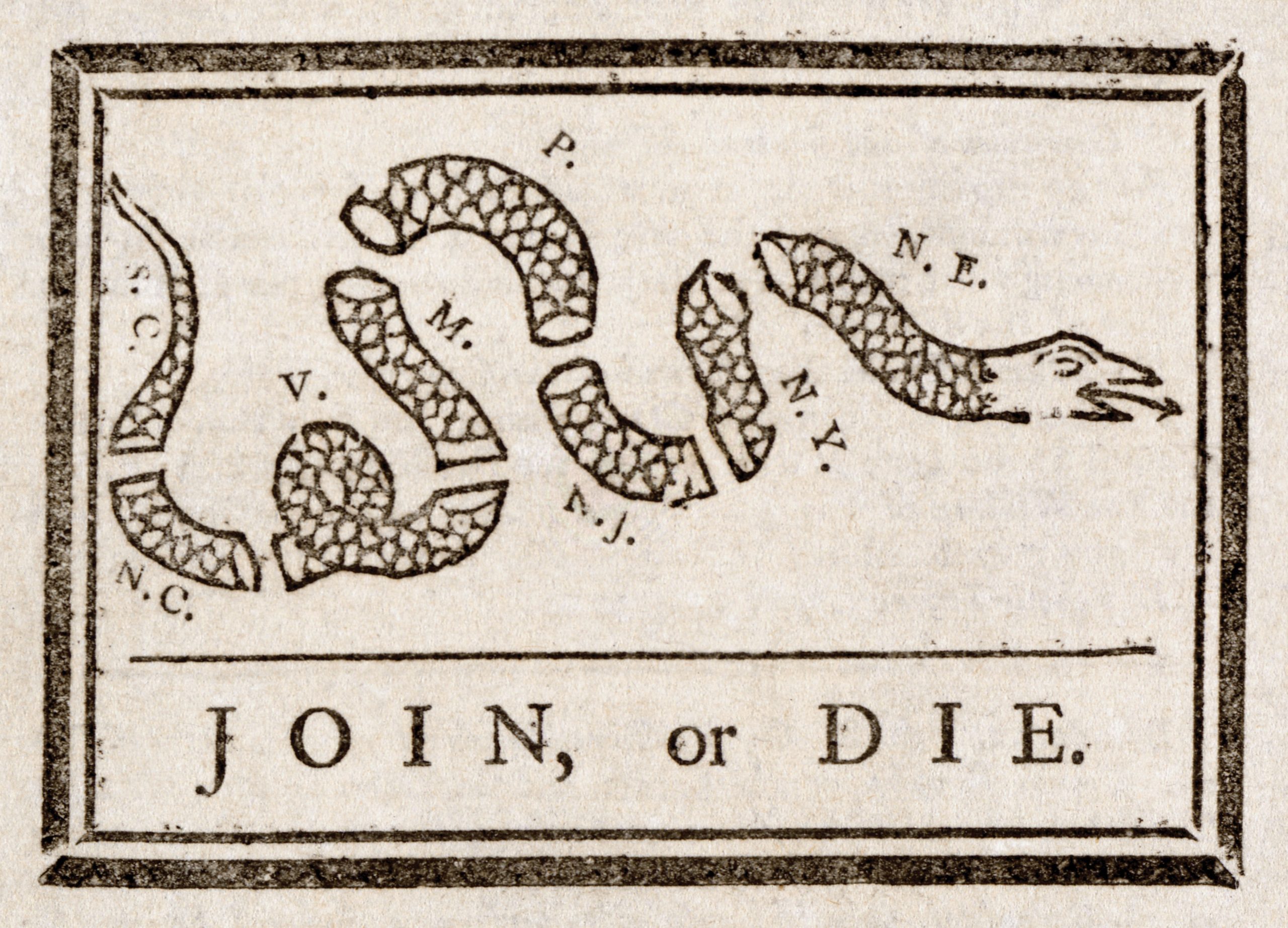

Although it was created to emphasize the need for unity among the American colonies, this famous 1754 graphic by Ben Franklin also illustrates a fundamental truth about structure: If the parts that make up a firm do not work together, the firm is likely to fail.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Sears’s new structure organized the firm around five types of divisions: (1) operating businesses (such as clothing, appliances, and electronics), (2) support units (certain functional areas such as marketing and finance), (3) brands (which focus on nurturing the firm’s various brands such as Lands’ End, Joe Boxer, Craftsman, and Kenmore), (4) online, and (5) real estate. At the time, Sears’s chairman Edward S. Lampert noted that “by creating smaller focused teams that are clearly responsible for their units, we [will] increase autonomy and accountability, create greater ownership and enable faster, better decisions (Retail Net).” Unfortunately, structural changes cannot cure all a company’s ills. As of July 2011, Sears’s stock was worth just over half what it had been worth five years earlier.

Sometimes structures become too complex and need to be simplified. Many observers believe that this description fits Cisco. The company’s CEO, John Chambers, has moved Cisco away from a hierarchical emphasis toward a focus on horizontal linkages. As of late 2009, Cisco had four types of such linkages. For any given project, a small team of people reported to one of forty-seven boards. The boards averaged fourteen members each. Forty-three of these boards each reported to one of twelve councils. Each council also averaged fourteen members. The councils reported to an operating committee consisting of Chambers and fifteen other top executives. Four of the forty-seven boards bypassed the councils and reported directly to the operating committee. These arrangements are so complex and time consuming that some top executives spend 30 percent of their work hours serving on more than ten of the boards, councils, and the operating committee.

Because it competes in fast-changing high-tech markets, Cisco needs to be able to make competitive moves quickly. The firm’s complex structural arrangements are preventing this. In late 2007, Hewlett-Packard (HP) started promoting a warranty service that provides free support and upgrades within the computer network switches market. Because Cisco’s response to this initiative had to work its way through multiple committees, the firm did not take action until April 2009. During the delay, Cisco’s share of the market dropped as customers embraced HP’s warranty. This problem and others created by Cisco’s overly complex structure were so severe that one columnist wondered aloud “has Cisco’s John Chambers lost his mind (Blodget, 2009)?” In the summer of 2011, Chambers reversed course and decided to return Cisco to a more traditional structure while reducing the firm’s workforce by 9 percent. Time will tell whether these structural changes will boost Cisco’s stock price, which remained flat between 2006 and mid-2011.

Key Takeaway

- Executives must select among the four types of structure (simple, functional, multidivisional, and matrix) available to organize operations. Each structure has unique advantages, and the selection of structures involves a series of trade-offs.

Exercises

- What type of structure best describes the organization of your college or university? What led you to reach your conclusion?

- The movie Office Space illustrates two types of structures. What are some other scenes or themes from movies that provide examples or insights relevant to understanding organizational structure?

References

Askenas, R., Ulrich, D., Jick, T., & Kerr, S. 1995. The boundaryless organization: Breaking down the chains of organizational structure. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Blodget, H. 2009, August 6. Has Cisco’s John Chambers lost his mind? Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/henry-blodget-has-ciscos-john- chambers-lost-his-mind-2009-8.

Elliott, D. 2011, July 3. New type of commander may avoid Katrina-like chaos. Yahoo! News. Retrieved from http://news.yahoo.com/type-commander-may-avoid-katrina-chaos-153 143508.html.

Hamel, G. 2007, September 27. What Google, Whole Foods do best. CNNMoney. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2007/09/26/news/companies/management_hamel. fortune/index.htm.

Jacobius, A. 2011, July 25. GE Capital slowly moving back into lending waters. Pensions & Investments. Retrieved from http://www.pionline.com/article/20110725/PRINTSUB/110729949.

Ketchen, D. J., & Short, J. C. 2011. Separating fads from facts: Lessons from “the good, the fad, and the ugly.” Business Horizons, 54, 17–22.

McWilliams, J. 2011, May 19. Coca-Cola names Bea Perez chief sustainability officer. Atlantic-Journal Constitution. Retrieved from http://www.ajc.com/business/coca-cola-names-bea-951741.html.

Retail Net, Sears restructures business units. Retail Net. Retrieved from http://www.retailnet.com /story.cfm?ID=41613.