47 8.2 Concentration Strategies

Learning Objectives

- Name and understand the three concentration strategies.

- Be able to explain horizontal integration and two reasons why it often fails.

For many firms, concentration strategies are very sensible. These strategies involve trying to compete successfully only within a single industry. McDonald’s, Starbucks, and Subway are three firms that have relied heavily on concentration strategies to become dominant players.

Table 8.1 Concentration Strategies

Concentration strategies involve trying to grow by successfully competing only within a single industry. WE illustrate the three concentration strategies below.

| Market penetration involves trying to gain additional share of a firm’s existing markets using existing products—often by relying on extensive advertising. Perhaps the most famous example of two close rivals simultaneously attempting market penetration is the “cola wars” where Coca-Cola and PepsiCo fight for share in the soft drink market. Pepsi’s blind taste tests in 1975 called the Pepsi Challenge is one of the more famous attacks in this ongoing battle. |

| Market development involves taking existing products and trying to sell them within new markets. Starbucks engages in market development by selling their beans and bottled drinks in grocery stores. Apple engages in market development by allowing customers in Starbucks stores to connect directly to iTunes store and Starbucks Now Playing content. Customers are offered a free download to get them to visit iTunes—and to perhaps purchase more songs. |

|

Product development involves creating new products to serve existing markets. King Gillette, an American businessman whose family hailed from France, pioneered the safety razor that bears his family name. His company’s more recent innovations in the razor market include Trac II (the first two-bald razor), Altra (first razor with a pivoting head), Sensor (first razor with spring-loaded blades), Mach 3 (first three-blade razor), and Fusion (first six-blade razor). Is the ten-blade razor coming soon? |

Market Penetration

There are three concentration strategies: (1) market penetration, (2) market development, and (3) product development (Table 8.1 “Concentration Strategies”). A firm can use one, two, or all three as part of their efforts to excel within an industry (Ansoff, 1957). Market penetration involves trying to gain additional share of a firm’s existing markets using existing products. Often firms will rely on advertising to attract new customers with existing markets.

Nike, for example, features famous athletes in print and television ads designed to take market share within the athletic shoes business from Adidas and other rivals. McDonald’s has pursued market penetration in recent years by using Latino themes within some of its advertising. The firm also maintains a Spanish-language website at http://www.meencanta.com; the website’s name is the Spanish translation of McDonald’s slogan “I’m lovin’ it.” McDonald’s hopes to gain more Latino customers through initiatives such as this website.

Nike relies in part on a market penetration strategy within the athletic shoe business.

Jean-louis Zimmermann – Nike, panneau d’affichange – CC BY 2.0.

Market Development

Market development involves taking existing products and trying to sell them within new markets. One way to reach a new market is to enter a new retail channel. Starbucks, for example, has stepped beyond selling coffee beans only in its stores and now sells beans in grocery stores. This enables Starbucks to reach consumers that do not visit its coffeehouses.

Starbucks’ market development strategy has allowed fans to buy its beans in grocery stores.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 2.0.

Entering new geographic areas is another way to pursue market development. Philadelphia-based Tasty Baking Company has sold its Tastykake snack cakes since 1914 within Pennsylvania and adjoining states. The firm’s products have become something of a cult hit among customers, who view the products as much tastier than the snack cakes offered by rivals such as Hostess and Little Debbie. In April 2011, Tastykake was purchased by Flowers Foods, a bakery firm based in Georgia. When it made this acquisition, Flower Foods announced its intention to begin extensively distributing Tastykake’s products within the southeastern United States. Displaced Pennsylvanians in the south rejoiced.

Product Development

Product development involves creating new products to serve existing markets. In the 1940s, for example, Disney expanded its offerings within the film business by going beyond cartoons and creating movies featuring real actors. More recently, McDonald’s has gradually moved more and more of its menu toward healthy items to appeal to customers who are concerned about nutrition.

In 2009, Starbucks introduced VIA, an instant coffee variety that executives hoped would appeal to their customers when they do not have easy access to a Starbucks store or a coffeepot. The soft drink industry is a frequent location of product development efforts. Coca-Cola and Pepsi regularly introduce new varieties—such as Coke Zero and Pepsi Cherry Vanilla—in an attempt to take market share from each other and from their smaller rivals.

Product development is a popular strategy in the soft-drink industry, but not all developments pay off. Coca-Cola Black (a blending of cola and coffee flavors) was launched in 2006 but discontinued in 2008.

Buglugs – Coca-Cola Blak 4pack – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Seattle-based Jones Soda Co. takes a novel approach to product development. Each winter, the firm introduces a holiday-themed set of unusual flavors. Jones Soda’s 2006 set focus on the flavors of Thanksgiving. It contained Green Pea, Sweet Potato, Dinner Roll, Turkey and Gravy, and Antacid sodas. The flavors of Christmas were the focus of 2007’s set, which included Sugar Plum, Christmas Tree, Egg Nog, and Christmas Ham. In early 2011, Jones Soda let it customers choose the winter 2011 flavors via a poll on its website. The winners were Candy Cane, Gingerbread, Pear Tree, and Egg Nog. None of these holiday flavors are expected to be big hits, of course. The hope is that the buzz that surrounds the unusual flavors each year will grab customers’ attention and get them to try—and become hooked on—Jones Soda’s more traditional flavors.

Horizontal Integration: Mergers and Acquisitions

Table 8.2 Horizontal Integration

Horizontal integrations refers to pursuing a concentration strategy by acquiring or merging with a rival. The term merger is generally used when two similarly sized firms are integrated into a single entity. In an acquisition, a larger firm purchases and absorbs a smaller firm. We illustrate examples of each below.

| ExxonMobil is a direct descendant of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. It was formed by the 1999 merger of Exxon and Mobil. As in many mergers, the new company name combines the old company names. |

| Starbucks acquired competitor Seattle’s Best Coffee—which had a presence in Borders Bookstores and Subway Restaurants—in order to target a more working-class audience without diluting the Starbucks brand. |

| Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard formed Hewlett-Packard in a garage after graduating from Stanford in 1935. In recent years, HP has pursued horizontal integration through a merger with Compaq and the acquisition of Palm. |

| DaimlerChrysler was formed in 1998 when Chrysler entered into what was billed as a “merger of equals” with Germany’s Daimler-Benz AG. The marriage failed, and Chrysler is currently owned by Italian automaker Fiat. |

| Global pharmaceutical firm GlaxoSmithKline plc was formed by the merger of GlaxoWellcome plc and SmithKline Beecham plc in 200. |

Rather than rely on their own efforts, some firms try to expand their presence in an industry by acquiring or merging with one of their rivals. This strategic move is known as horizontal integration (Table 8.2 “Horizontal Integration”). An acquisition takes place when one company purchases another company. Generally, the acquired company is smaller than the firm that purchases it. A merger joins two companies into one. Mergers typically involve similarly sized companies. Disney was much bigger than Miramax and Pixar when it joined with these firms in 1993 and 2006, respectively, thus these two horizontal integration moves are considered to be acquisitions.

Horizontal integration can be attractive for several reasons. In many cases, horizontal integration is aimed at lowering costs by achieving greater economies of scale. This was the reasoning behind several mergers of large oil companies, including BP and Amoco in 1998, Exxon and Mobil in 1999, and Chevron and Texaco in 2001. Oil exploration and refining is expensive. Executives in charge of each of these six corporations believed that greater efficiency could be achieved by combining forces with a former rival. Considering horizontal integration alongside Porter’s five forces model highlights that such moves also reduce the intensity of rivalry in an industry and thereby make the industry more profitable.

Some purchased firms are attractive because they own strategic resources such as valuable brand names. Acquiring Tasty Baking was appealing to Flowers Foods, for example, because the name Tastykake is well known for quality in heavily populated areas of the northeastern United States. Some purchased firms have market share that is attractive. Part of the motivation behind Southwest Airlines’ purchase of AirTran was that AirTran had a significant share of the airline business in cities—especially Atlanta, home of the world’s busiest airport—that Southwest had not yet entered. Rather than build a presence from nothing in Atlanta, Southwest executives believed that buying a position was prudent.

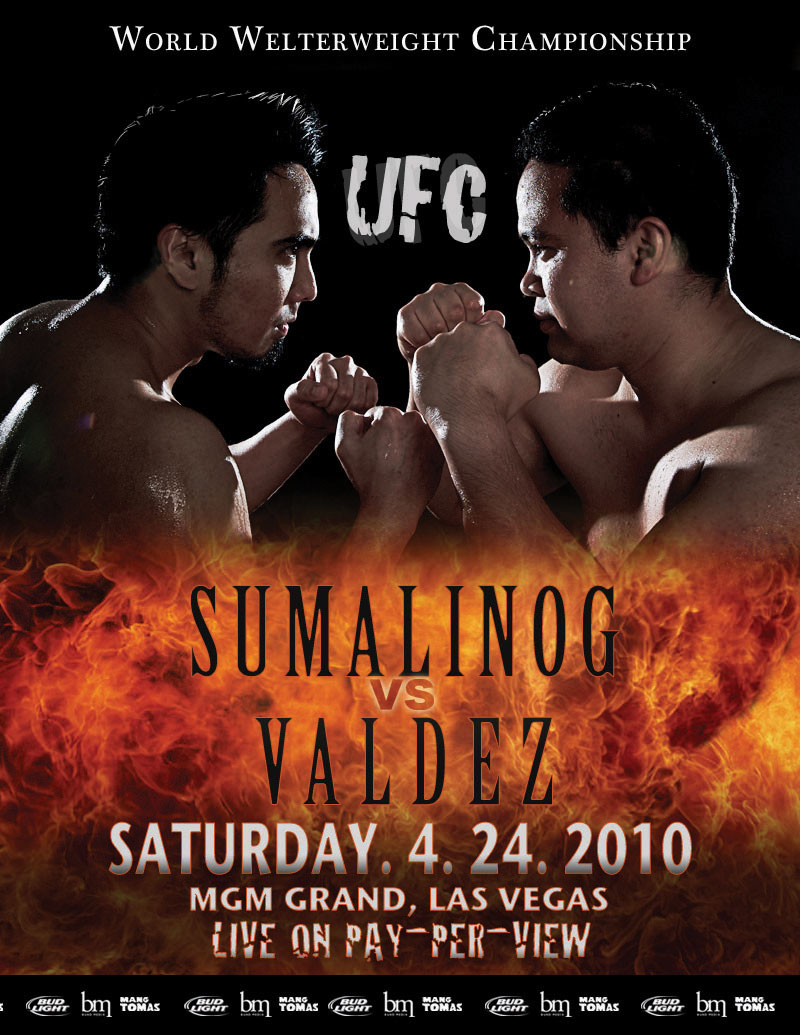

Horizontal integration can also provide access to new distribution channels. Some observers were puzzled when Zuffa, the parent company of the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), purchased rival mixed martial arts (MMA) promotion Strikeforce. UFC had such a dominant position within MMA that Strikeforce seemed to add very little for Zuffa. Unlike UFC, Strikeforce had gained exposure on network television through broadcasts on CBS and its partner Showtime. Thus acquiring Strikeforce might help Zuffa gain mainstream exposure of its product (Wagenheim, 2011).

The combination of UFC and Strikeforce into one company may accelerate the growing popularity of mixed martial arts.

Ben Ahhi – UFC POSTER-fire – CC BY 2.0.

Despite the potential benefits of mergers and acquisitions, their financial results often are very disappointing. One study found that more than 60 percent of mergers and acquisitions erode shareholder wealth while fewer than one in six increases shareholder wealth (Henry, 2002). Some of these moves struggle because the cultures of the two companies cannot be meshed. This chapter’s opening vignette suggests that Disney and Pixar may be experiencing this problem. Other acquisitions fail because the buyer pays more for a target company than that company is worth and the buyer never earns back the premium it paid.

In the end, between 30 percent and 45 percent of mergers and acquisitions are undone, often at huge losses (Hitt, et. al., 2001). For example, Mattel purchased The Learning Company in 1999 for $3.6 billion and sold it a year later for $430 million—12 percent of the original purchase price. Similarly, Daimler-Benz bought Chrysler in 1998 for $37 billion. When the acquisition was undone in 2007, Daimler recouped only $1.5 billion worth of value—a mere 4 percent of what it paid. Thus executives need to be cautious when considering using horizontal integration.

Key Takeaways

- A concentration strategy involves trying to compete successfully within a single industry.

- Market penetration, market development, and product development are three methods to grow within an industry. Mergers and acquisitions are popular moves for executing a concentration strategy, but executives need to be cautious about horizontal integration because the results are often poor.

Exercises

- Suppose the president of your college or university decided to merge with or acquire another school. What schools would be good candidates for this horizontal integration move? Would the move be a success?

- Given that so many mergers and acquisitions fail, why do you think that executives keep making horizontal integration moves?

- Can you identify a struggling company that could benefit from market penetration, market development, or product development? What might you advise this company’s executives to do differently?

References

Ansoff, H. I. 1957. Strategies for diversification. Harvard Business Review, 35(5), 113–124.

Henry, D. 2002, October 14. Mergers: Why most big deals don’t pay off. Business Week, 60–70.

Hitt, M. A., Harrison, J. S., & Ireland, R. D. 2001. Mergers and acquisitions: A guide to creating value for stakeholders. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Wagenheim, J. 2011, March 12. UFC buys out Strikeforce in another step toward global domination. SI.com. Retrieved from http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2011/writers/jeff_wagenheim/03/12/strikeforce-purchased/index.html.