190 23.11 Reactance, Inductive and Capacitive

Summary

- Sketch voltage and current versus time in simple inductive, capacitive, and resistive circuits.

- Calculate inductive and capacitive reactance.

- Calculate current and/or voltage in simple inductive, capacitive, and resistive circuits.

Many circuits also contain capacitors and inductors, in addition to resistors and an AC voltage source. We have seen how capacitors and inductors respond to DC voltage when it is switched on and off. We will now explore how inductors and capacitors react to sinusoidal AC voltage.

Inductors and Inductive Reactance

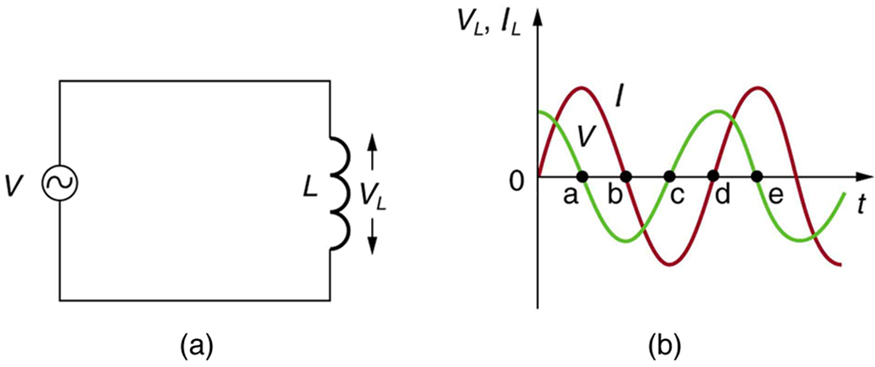

Suppose an inductor is connected directly to an AC voltage source, as shown in Figure 1. It is reasonable to assume negligible resistance, since in practice we can make the resistance of an inductor so small that it has a negligible effect on the circuit. Also shown is a graph of voltage and current as functions of time.

The graph in Figure 2(b) starts with voltage at a maximum. Note that the current starts at zero and rises to its peak after the voltage that drives it, just as was the case when DC voltage was switched on in the preceding section. When the voltage becomes negative at point a, the current begins to decrease; it becomes zero at point b, where voltage is its most negative. The current then becomes negative, again following the voltage. The voltage becomes positive at point c and begins to make the current less negative. At point d, the current goes through zero just as the voltage reaches its positive peak to start another cycle. This behavior is summarized as follows:

AC Voltage in an Inductor

When a sinusoidal voltage is applied to an inductor, the voltage leads the current by one-fourth of a cycle, or by a [latex]{90^{\circ}}[/latex] phase angle.

Current lags behind voltage, since inductors oppose change in current. Changing current induces a back emf [latex]{V= -L(\Delta I/ \Delta t)}[/latex]. This is considered to be an effective resistance of the inductor to AC. The rms current [latex]{I}[/latex] through an inductor [latex]{L}[/latex] is given by a version of Ohm’s law:

where [latex]{V}[/latex] is the rms voltage across the inductor and [latex]{X_L}[/latex] is defined to be

with [latex]{f}[/latex] the frequency of the AC voltage source in hertz (An analysis of the circuit using Kirchhoff’s loop rule and calculus actually produces this expression). [latex]{X_L}[/latex] is called the inductive reactance, because the inductor reacts to impede the current. [latex]{X_L}[/latex] has units of ohms ([latex]{1 \;\text{H}=1 \;\Omega \cdot \;\text{s}}[/latex], so that frequency times inductance has units of (cycles/s)([latex]{\Omega \cdot \;\text{s}}[/latex])= [latex]{\Omega}[/latex]), consistent with its role as an effective resistance. It makes sense that [latex]{X_L}[/latex] is proportional to [latex]{L}[/latex], since the greater the induction the greater its resistance to change. It is also reasonable that [latex]{X_L}[/latex] is proportional to frequency [latex]{f}[/latex], since greater frequency means greater change in current. That is, [latex]{\Delta I/ \Delta t}[/latex] is large for large frequencies (large [latex]{f}[/latex], small [latex]{\Delta t}[/latex]). The greater the change, the greater the opposition of an inductor.

Example 1: Calculating Inductive Reactance and then Current

(a) Calculate the inductive reactance of a 3.00 mH inductor when 60.0 Hz and 10.0 kHz AC voltages are applied. (b) What is the rms current at each frequency if the applied rms voltage is 120 V?

Strategy

The inductive reactance is found directly from the expression [latex]{X_L = 2 \pi fL}[/latex]. Once [latex]{X_L}[/latex] has been found at each frequency, Ohm’s law as stated in the Equation [latex]{I=V/X_L}[/latex] can be used to find the current at each frequency.

Solution for (a)

Entering the frequency and inductance into Equation [latex]{X_L = 2 \pi fL}[/latex] gives

Similarly, at 10 kHz,

Solution for (b)

The rms current is now found using the version of Ohm’s law in Equation [latex]{I = V/X_L}[/latex], given the applied rms voltage is 120 V. For the first frequency, this yields

Similarly, at 10 kHz,

Discussion

The inductor reacts very differently at the two different frequencies. At the higher frequency, its reactance is large and the current is small, consistent with how an inductor impedes rapid change. Thus high frequencies are impeded the most. Inductors can be used to filter out high frequencies; for example, a large inductor can be put in series with a sound reproduction system or in series with your home computer to reduce high-frequency sound output from your speakers or high-frequency power spikes into your computer.

Note that although the resistance in the circuit considered is negligible, the AC current is not extremely large because inductive reactance impedes its flow. With AC, there is no time for the current to become extremely large.

Capacitors and Capacitive Reactance

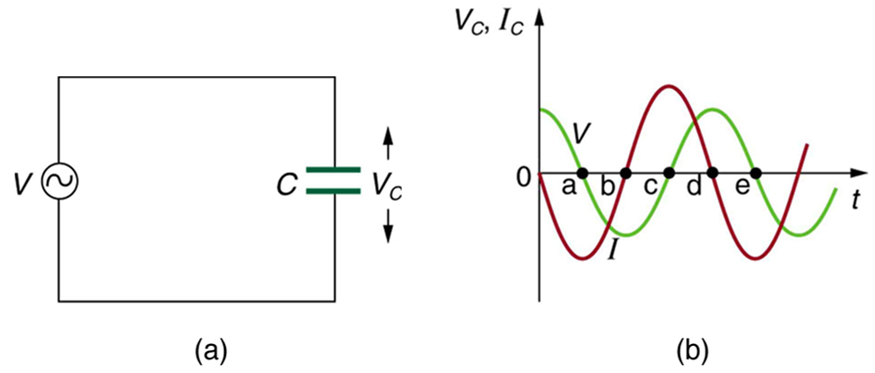

Consider the capacitor connected directly to an AC voltage source as shown in Figure 2. The resistance of a circuit like this can be made so small that it has a negligible effect compared with the capacitor, and so we can assume negligible resistance. Voltage across the capacitor and current are graphed as functions of time in the figure.

The graph in Figure 2 starts with voltage across the capacitor at a maximum. The current is zero at this point, because the capacitor is fully charged and halts the flow. Then voltage drops and the current becomes negative as the capacitor discharges. At point a, the capacitor has fully discharged ([latex]{Q = 0}[/latex] on it) and the voltage across it is zero. The current remains negative between points a and b, causing the voltage on the capacitor to reverse. This is complete at point b, where the current is zero and the voltage has its most negative value. The current becomes positive after point b, neutralizing the charge on the capacitor and bringing the voltage to zero at point c, which allows the current to reach its maximum. Between points c and d, the current drops to zero as the voltage rises to its peak, and the process starts to repeat. Throughout the cycle, the voltage follows what the current is doing by one-fourth of a cycle:

AC Voltage in a Capacitor

When a sinusoidal voltage is applied to a capacitor, the voltage follows the current by one-fourth of a cycle, or by a [latex]{90^{\circ}}[/latex] phase angle.

The capacitor is affecting the current, having the ability to stop it altogether when fully charged. Since an AC voltage is applied, there is an rms current, but it is limited by the capacitor. This is considered to be an effective resistance of the capacitor to AC, and so the rms current [latex]{I}[/latex] in the circuit containing only a capacitor [latex]{C}[/latex] is given by another version of Ohm’s law to be

where [latex]{V}[/latex] is the rms voltage and [latex]{X_C}[/latex] is defined (As with [latex]{X_L}[/latex], this expression for [latex]{X_C}[/latex] results from an analysis of the circuit using Kirchhoff’s rules and calculus) to be

where [latex]{X_C}[/latex] is called the capacitive reactance, because the capacitor reacts to impede the current. [latex]{X_C}[/latex] has units of ohms (verification left as an exercise for the reader). [latex]{X_C}[/latex] is inversely proportional to the capacitance [latex]{C}[/latex]; the larger the capacitor, the greater the charge it can store and the greater the current that can flow. It is also inversely proportional to the frequency [latex]{f}[/latex]; the greater the frequency, the less time there is to fully charge the capacitor, and so it impedes current less.

Example 2: Calculating Capacitive Reactance and then Current

(a) Calculate the capacitive reactance of a 5.00 mF capacitor when 60.0 Hz and 10.0 kHz AC voltages are applied. (b) What is the rms current if the applied rms voltage is 120 V?

Strategy

The capacitive reactance is found directly from the expression in [latex]{X_C = \frac{1}{2 \pi fC}}[/latex]. Once [latex]{X_C}[/latex] has been found at each frequency, Ohm’s law stated as [latex]{I = V/X_C}[/latex] can be used to find the current at each frequency.

Solution for (a)

Entering the frequency and capacitance into [latex]{X_C = \frac{1}{2 \pi fC}}[/latex] gives

Similarly, at 10 kHz,

Solution for (b)

The rms current is now found using the version of Ohm’s law in [latex]{I = V/X_C}[/latex], given the applied rms voltage is 120 V. For the first frequency, this yields

Similarly, at 10 kHz,

Discussion

The capacitor reacts very differently at the two different frequencies, and in exactly the opposite way an inductor reacts. At the higher frequency, its reactance is small and the current is large. Capacitors favor change, whereas inductors oppose change. Capacitors impede low frequencies the most, since low frequency allows them time to become charged and stop the current. Capacitors can be used to filter out low frequencies. For example, a capacitor in series with a sound reproduction system rids it of the 60 Hz hum.

Although a capacitor is basically an open circuit, there is an rms current in a circuit with an AC voltage applied to a capacitor. This is because the voltage is continually reversing, charging and discharging the capacitor. If the frequency goes to zero (DC), [latex]{X_C}[/latex] tends to infinity, and the current is zero once the capacitor is charged. At very high frequencies, the capacitor’s reactance tends to zero—it has a negligible reactance and does not impede the current (it acts like a simple wire). Capacitors have the opposite effect on AC circuits that inductors have.

Resistors in an AC Circuit

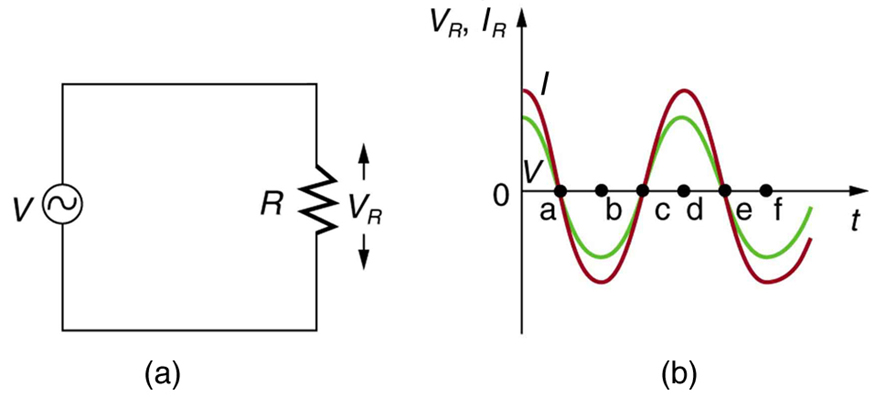

Just as a reminder, consider Figure 3, which shows an AC voltage applied to a resistor and a graph of voltage and current versus time. The voltage and current are exactly in phase in a resistor. There is no frequency dependence to the behavior of plain resistance in a circuit:

AC Voltage in a Resistor

When a sinusoidal voltage is applied to a resistor, the voltage is exactly in phase with the current—they have a [latex]{0^{\circ}}[/latex] phase angle.

Section Summary

- For inductors in AC circuits, we find that when a sinusoidal voltage is applied to an inductor, the voltage leads the current by one-fourth of a cycle, or by a [latex]{90^{\circ}}[/latex] phase angle.

- The opposition of an inductor to a change in current is expressed as a type of AC resistance.

- Ohm’s law for an inductor is

[latex]{I =}[/latex] [latex]{\frac{V}{X_L}},[/latex]

where [latex]{V}[/latex] is the rms voltage across the inductor.

- [latex]{X_L}[/latex] is defined to be the inductive reactance, given by

[latex]{X_L = 2 \pi fL},[/latex]

with [latex]{f}[/latex] the frequency of the AC voltage source in hertz.

- Inductive reactance [latex]{X_L}[/latex] has units of ohms and is greatest at high frequencies.

- For capacitors, we find that when a sinusoidal voltage is applied to a capacitor, the voltage follows the current by one-fourth of a cycle, or by a [latex]{90^{\circ}}[/latex] phase angle.

- Since a capacitor can stop current when fully charged, it limits current and offers another form of AC resistance; Ohm’s law for a capacitor is

[latex]{I =}[/latex] [latex]{\frac{V}{X_C}},[/latex]

where [latex]{V}[/latex] is the rms voltage across the capacitor.

- [latex]{X_C}[/latex] is defined to be the capacitive reactance, given by

[latex]{X_C =}[/latex] [latex]{\frac{1}{2 \pi fC}}.[/latex]

- [latex]{X_C}[/latex] has units of ohms and is greatest at low frequencies.

Conceptual Questions

1: Presbycusis is a hearing loss due to age that progressively affects higher frequencies. A hearing aid amplifier is designed to amplify all frequencies equally. To adjust its output for presbycusis, would you put a capacitor in series or parallel with the hearing aid’s speaker? Explain.

2: Would you use a large inductance or a large capacitance in series with a system to filter out low frequencies, such as the 100 Hz hum in a sound system? Explain.

3: High-frequency noise in AC power can damage computers. Does the plug-in unit designed to prevent this damage use a large inductance or a large capacitance (in series with the computer) to filter out such high frequencies? Explain.

4: Does inductance depend on current, frequency, or both? What about inductive reactance?

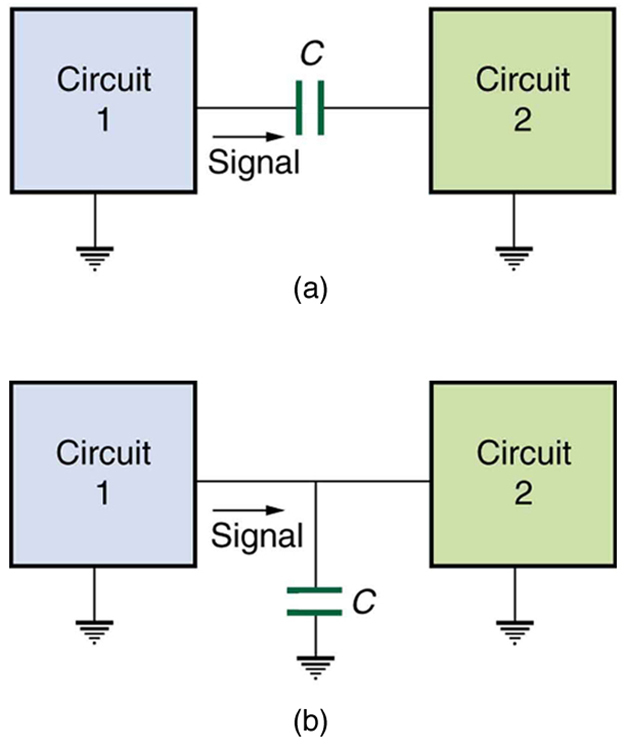

6: If the capacitors in Figure 4 are replaced by inductors, which acts as a low-frequency filter and which as a high-frequency filter?

Problems & Exercises

1: At what frequency will a 30.0 mH inductor have a reactance of [latex]{100 \;\Omega}[/latex]

2: What value of inductance should be used if a [latex]{20.0 \;\text{k} \Omega}[/latex] reactance is needed at a frequency of 500 Hz?

3: What capacitance should be used to produce a [latex]{2.00 \;\text{M} \Omega}[/latex] reactance at 60.0 Hz?

4: At what frequency will an 80.0 mF capacitor have a reactance of [latex]{0.250 \;\Omega}[/latex]?

5: (a) Find the current through a 0.500 H inductor connected to a 60.0 Hz, 480 V AC source. (b) What would the current be at 100 kHz?

6: (a) What current flows when a 60.0 Hz, 480 V AC source is connected to a [latex]{0.250 \;\mu F}[/latex] capacitor? (b) What would the current be at 25.0 kHz?

7: A 20.0 kHz, 16.0 V source connected to an inductor produces a 2.00 A current. What is the inductance?

8: A 20.0 Hz, 16.0 V source produces a 2.00 mA current when connected to a capacitor. What is the capacitance?

9: (a) An inductor designed to filter high-frequency noise from power supplied to a personal computer is placed in series with the computer. What minimum inductance should it have to produce a [latex]{2.00 \;\text{k} \Omega}[/latex] reactance for 15.0 kHz noise? (b) What is its reactance at 60.0 Hz?

10: The capacitor in Figure 4(a) is designed to filter low-frequency signals, impeding their transmission between circuits. (a) What capacitance is needed to produce a [latex]{100 \;\text{k} \Omega}[/latex] reactance at a frequency of 120 Hz? (b) What would its reactance be at 1.00 MHz? (c) Discuss the implications of your answers to (a) and (b).

11: The capacitor in Figure 4(b) will filter high-frequency signals by shorting them to earth/ground. (a) What capacitance is needed to produce a reactance of [latex]{10.0 \;\text{m} \Omega}[/latex] for a 5.00 kHz signal? (b) What would its reactance be at 3.00 Hz? (c) Discuss the implications of your answers to (a) and (b).

12: Unreasonable Results

In a recording of voltages due to brain activity (an EEG), a 10.0 mV signal with a 0.500 Hz frequency is applied to a capacitor, producing a current of 100 mA. Resistance is negligible. (a) What is the capacitance? (b) What is unreasonable about this result? (c) Which assumption or premise is responsible?

13: Construct Your Own Problem

Consider the use of an inductor in series with a computer operating on 60 Hz electricity. Construct a problem in which you calculate the relative reduction in voltage of incoming high frequency noise compared to 60 Hz voltage. Among the things to consider are the acceptable series reactance of the inductor for 60 Hz power and the likely frequencies of noise coming through the power lines.

Glossary

- inductive reactance

- the opposition of an inductor to a change in current; calculated by [latex]{X_L = 2 \pi fL}[/latex]

- capacitive reactance

- the opposition of a capacitor to a change in current; calculated by [latex]{X_C = \frac{1}{2 \pi fC}}[/latex]

Solutions

Problems & Exercises

1: 531 Hz

3: 1.33 nF

5: (a) 2.55 A

(b) 1.53 mA

7: [latex]{63.7 \;\mu H}[/latex]

9: (a) 21.2 mH

(b) [latex]{8.00 \;\Omega}[/latex]

11: (a) 3.18 mF

(b) [latex]{16.7 \;\Omega}[/latex]