Evolving Into the Open: A Framework for Collaborative Design of Renewable Assignments

Stacy Katz and Jennifer Van Allen

Authors

- Stacy Katz, Lehman College

- Jennifer Van Allen, Ed.D., Lehman College

Project Overview

Institution: Lehman College

Institution Type: public, liberal arts, undergraduate, postgraduate

Project Discipline: Education

Project Outcome: student-created lesson plans

Tools Used: OER Commons

Resources Included in Chapter:

- Renewable Assignment Design Framework

- Recommended Sources

- Course Assignment

- Grading Rubric

Introduction

“Come for the cost savings, stay for the pedagogy,” is a popular sentiment in the open education community. The significant cost savings associated with the adoption of Open Educational Resources, OER (Hilton et al., 2014; Ikahihifo et al., 2017) creates accessible opportunities in education for students of all ages. Understanding the impact of OER as a practice is nascent and difficult to measure. Indeed, some argue that standard research methods are insufficient for explicating the benefits of free access to knowledge through OER (Grimaldi et al., 2019). If we cannot sufficiently understand what it means for students to access materials, we can only begin to imagine the shift to open pedagogy. This design is a student-centered teaching approach that empowers students as creators of knowledge and open resources (DeRosa & Robison, 2017), as well as promotes and potentially maximizes learning outcomes. As the integration of OER within classes compels instructors to reconsider the assigned course materials, open pedagogy recasts the role of course assignments and activities students engage in within a course. Yet, many are grappling with how to create and redesign assignments to engage students in open pedagogy. In this chapter, we make a case for applying open pedagogy in teacher education coursework and, utilizing a specific case, describe the Renewable Assignment Design Framework that may be adapted by librarians and faculty when planning for open educational practices.

In 2009, Greenhow et al. predicted that participatory, collaborative, and distributed practices provided through connected platforms on the Internet would have a profound effect on teaching and learning. As OER initiatives have taken hold in education, some instructors have begun to integrate open teaching practices into their coursework (Veletsianos & Kimmons, 2012). Through open licensing, not only is access to knowledge more freely available, but knowledge can also be created and shaped allowing content to develop in unique ways. “Knowledge consumption and knowledge creation are not separate but parallel processes, as knowledge is co-constructed, contextualized, cumulative, iterative, and recursive” (DeRosa & Jhangiani, 2017, p. 13). This is the basic premise of an open pedagogical approach in which an instructor guides students to curate and create new knowledge, empowering them as public contributors of ideas through open content as they learn and grow in their disciplinary knowledge (DeRosa & Robison, 2017). At the same time, the instructor is also supporting students in developing digital literacy skills which help them become part of an open network that can support their learning beyond the classroom (Cronin, 2017).

Of students attending the City University of New York (CUNY), 37.1 percent have household incomes of less than $20,000 per year (CUNY Office of Institutional Research and Assessment, 2017). CUNY librarians have long been aware of the high use of the reserve collections and recognized OER as a path to provide free online access to materials for students and renew faculty pedagogy (Amaral, 2018). Since librarians possess expertise in searching collections, resource evaluation, copyright, and Creative Commons licensing, they are uniquely positioned to engage faculty in curating and adapting OER. Therefore, initiatives began at multiple CUNY colleges to reduce textbook costs. Beginning in 2017, funding from New York State was allocated to the CUNY Office of Library Services to support OER adoption and creation across institutions. As a result, Lehman College, the only four-year public institution in the Bronx and a part of CUNY, was allocated funding to continue its OER initiative to train and incentivize faculty in adopting and creating OER (for more specific information about this funding, see CUNY, n.d.). Participation at Lehman College has been based on faculty interest and distributed across all the schools in the college (Katz, 2019). Since the start of the CUNY initiative, students have reported that, in addition to saving them money, the materials for OER courses they have taken were, by and large, easier to access and better for learning (Brandle et al., 2019). Through the process of adopting and curating OER, faculty have engaged in more intentional pedagogy by ensuring that resources are specifically aligned to course outcomes. These outcomes have met the primary and secondary goals of the CUNY OER Scale Up initiative to decrease costs and barriers to access for students, as well as align curriculum and pedagogy to learning outcomes (CUNY, n.d.).

Open pedagogy emerged as a popular trend in the New York State Open Educational Resources Funds CUNY Year One Report, as “OER offers faculty the opportunity to engage students in open pedagogy, where students take on the role of knowledge creators and share their work and their learning with others” (CUNY, 2018). The enthusiasm for open pedagogy within CUNY created the buzz to interest faculty and offer a workshop on it at Lehman College in Fall 2018. It was through this work that our collaborative partnership emerged. Stacy Katz, a library faculty member at Lehman College, developed the school’s OER initiative, in which she supported faculty in curating and creating OER for their courses. Jennifer Van Allen, a teacher education faculty member at Lehman College, participated in the initiative through redesigning a course using OER and open pedagogy. Jennifer’s course, Language, Literacy, and Educational Technology, which was designed for inservice teacher candidates seeking an advanced degree in literacy studies, provided an opportunity to collaborate on and experiment with open pedagogy. OER use in teacher education courses allows teaching candidates to become familiar with open teaching resources available for use in K-12 classrooms and resources that can further their own professional growth after they graduate. At the same time, OER encourages teaching candidates to become important collaborators of open teaching materials (Sapire & Reed, 2011). As the course instructor, Jennifer was intimately familiar with the assignment and course learning outcomes, while Stacy provided expertise in open platforms and Creative Commons licensing. Our experiences resulted in the creation of a framework for developing renewable assignments (Renewable Assignment Design Framework) described below.

Renewable Assignments

Renewable assignments, as opposed to disposable assignments, are defined as tasks in which students compile and openly publish their work so that the assignment outcome is inherently valuable to the community (Chen, 2018; Wiley & Hilton, 2018). Wiley and Hilton (2018) have defined categories of assignments to show the spectrum between those that are disposable and renewable. In their criteria, assignments can be sorted as disposable, authentic, constructionist, and renewable. The disposable assignment which involves a student-created artifact submitted to the instructor, meets the most basic criterion of any assignment. When the value of that artifact extends beyond the students’ own learning, such as the creation of content tutorials for future classes, it falls into the category of an authentic assignment. In the constructionist assignment, students make an authentic assignment publicly available. To be considered renewable, the teacher invites the students to openly license and publicly share their work with the global community. In some cases, renewable assignments may be originally developed by the students, and in others, students may remix or adapt existing OER (Wiley & Hilton, 2018).

Originally, the assignment Jennifer chose to redesign was an authentic assignment in which the teaching candidates were required to develop an inquiry-based curriculum unit that supported their K-12 students in engaging with and developing digital literacy skills. This made it an ideal assignment to redesign so that candidates’ work had the potential for broader impact and value to others (see Appendix A for the original and redesigned assignment descriptions). Since the teaching candidates implemented the unit in their classrooms affecting the learning of their K-12 students, the assignment already had value beyond the candidates’ own learning. Through our collaborative process, the final assignment was broadened. Rather than limiting the teaching candidates to creating inquiry units, the redesigned renewable project allowed them to explore current K-12 OER and either remix, revise, adapt, or create a new OER that creatively demonstrates how to integrate technology or new literacies into their classrooms to support literacy learning. In addition to implementing the project in their own classrooms, the teaching candidates were invited to publicly share their work with the global teaching community using a Creative Commons license. Since the redesigned assignment has value to their K-12 students and the teaching community through a publicly shared and openly licensed artifact, it is considered a renewable assignment.

Renewable Assignment Design Framework

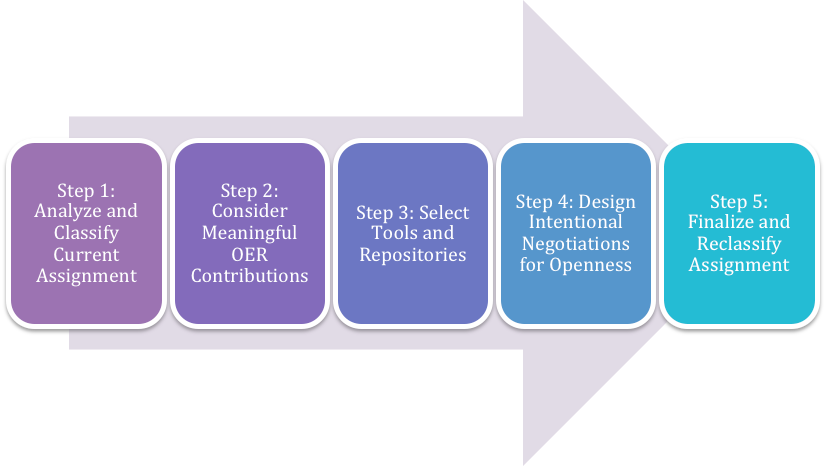

Using our experiences of redesigning the assignment from authentic to renewable, we developed the Renewable Assignment Design Framework (see Figure 1) to provide a process for our work, as well as to help others consider ways to develop open pedagogy practices. While our collaborative work on the renewable assignment described in the chapter took approximately two months, timelines may vary for others. Variables such as levels of support, technical skill, knowledge of OER tools and repositories, and other demands on faculty and librarian time may shorten or extend the timeframe for others. We provide our experience working through each of the steps together to redesign the assignment as well as to discuss recommendations and considerations for others implementing the framework within their community. These steps are not intended as a dogmatic practice, but rather a process of faculty reflection and intentional assignment development to position students as creators of meaningful open content.

Step 1: Analyze and Classify Current Assignment

As Lee and Barnett (1994, p. 17) explain, “Before one can change something, it is necessary to know what is occurring now.” Analyzing an assignment through reflective dialogue set the stage for the change process. Before redesigning the assignment, we examined the description and rubric of the class’s major assignment using Wiley and Hilton’s (2018) four-part test for categorizing an assignment as disposable, authentic, constructive, or renewable. This four-part test consists of the following questions:

- Are students asked to create new artifacts (essays, poems, videos, songs, etc.) or revise/remix existing OER?

- Does the new artifact have value beyond supporting the learning of its author?

- Are students invited to publicly share their new artifacts or revised/remixed OER?

- Are students invited to openly license their new artifacts or revised/remixed OER? (Wiley & Hilton, 2018)

During our discussion, Jennifer articulated the assignment description and goals, while Stacy asked reflective questions to clarify details about the original assignment. In order to analyze the original assignment, we assessed where it belonged within Wiley and Hilton’s (2018) criteria for renewable assignments. Since the students were practicing teachers, they utilized the unit plan they developed in their current K-12 classrooms. We, therefore, categorized the original assignment as authentic because it had value beyond Jennifer’s course to the K-12 students in the teaching candidates’ classrooms. The assignment was not renewable, however, because it was not publicly and openly shared with others. Our reflective dialogue about our analysis and classification of the assignment clarified intentional decisions that needed to be made during the redesign.

Considerations for Implementation

Redesigning an assignment to be renewable functions as a change process in which faculty develop greater self-awareness of their pedagogical practices and goals for their course. Given that syllabi and course assignments may be inherited and that faculty have competing demands that often limit their intentionality in planning, reflection is a critical component for envisioning new possibilities. When working with faculty to analyze and classify assignments, librarians may consider facilitating a reflective discussion. Questions and prompts posed by the librarian encourage the instructor to reflect on the course goals, an assignment’s purpose, and the desired learning outcomes for students. Examples of reflective prompts include:

- Tell me about your course goals.

- What reasoning guided the process and product of this assignment?

- What kinds of learning outcomes do you want to occur as a result of this assignment?

For more information about leading a reflective discussion, see Lee and Barnett (1994).

During the conversation, the librarian may raise points from Wiley and Hilton’s (2018) four-part test. As a result of this dialogue, the librarian will more fully understand the context of the course and the assignment. Additionally, the discussion will broaden and deepen the instructor’s understanding of their praxis, the course, and the assignment. Once both collaborators agree upon which category the original assignment fits into and fully understand the assignment outcomes, they can then begin to consider how the assignment might be modified to make it renewable as the collaboration moves forward.

Step 2: Consider Meaningful OER Contributions

After fully analyzing and classifying the assignment, we considered how it contributed to knowledge within the field of education. Using resources highlighted during the workshop on open pedagogy, which sparked Jennifer’s interest in open pedagogy, we explored examples of renewable assignments in various disciplines. These included student contributions to a test bank in a psychology course (Jhangiani, 2018), the creation of an anthology of early American literature with front matter for each text written and edited by students in an English literature course (DeRosa, 2016), and a project in which students edited a Wikipedia page to create more robust entries on places within their community in an interdisciplinary course (Montgomery & Leonard, 2015). Each of these examples helped us understand how OER contributions should be meaningful within the discipline or a broader community. While some of these examples contribute to course development through supporting the school community, others add to the discipline by developing open resources on the topic.

In considering the inquiry unit assignment, Jennifer provided expertise on what a meaningful contribution would look like in education. Since teachers value resources that can be used within K-12 classrooms, it was logical to revise the assignment to develop a broad range of classroom resources from lesson plans to online modules to a multimodal open book chapter for their students. As Jennifer began to think through these ideas, she shared these ideas with Stacy, who provided resources and continued to ask reflective questions about what changes might meet the criteria of a meaningful contribution in education for teachers and the learning outcomes of the assignment.

Considerations for Implementation

An important step in the process of redesigning an assignment is considering how an artifact might be meaningful within a discipline or broader community. What is meaningful can vary greatly based on the course context, the field, and the desired impact of the project. Student learning outcomes need to not only address course content knowledge but also support students’ development of disciplinary literacy skills. At the same time, when designing a renewable assignment, the instructor should consider how to support students in treating the project as an opportunity to contribute and empower them to view themselves as experts. Open pedagogy provides an opportunity for “students to learn as co-investigators so that they realize a model beyond the banking paradigm for their education” (Rosen & Smale, 2015, para. 13). Therefore, the librarian’s role is to support the brainstorming process by curating relevant examples of renewable assignments. Resources that provide guidance, as well as examples, include:

- Guide to Making Open Textbooks With Students – an open textbook for faculty interested in learning how to develop open textbooks with students

- Open Pedagogy Notebook – a website curating examples of renewable projects in higher education classrooms, which includes examples of open pedagogy at the assignment, course, and program level

Open pedagogy course examples include:

- DS 106 – an open online course where students build an assignment bank

- Eng 2001 – a literature course in which students build the glossary for their assigned readings

In addition, the librarian may continue to facilitate reflective dialogue supporting the instructor in connecting to the assignment goal and meaningful open contributions within the discipline and/or community. Once the instructor envisions a meaningful open contribution, the librarian can provide recommendations of appropriate tools and repositories for students to share their work.

Step 3: Select Tools and Repositories

Next, we explored the tools and repositories for open resources commonly used by educators. As the OER librarian, Stacy was familiar with the available tools and repositories that could be used by faculty and students to openly publish work. CUNY faculty have written, curated, and shared OER using a variety of tools, such as CUNY Academic Commons (a WordPress instance), CUNY OER Commons (an OER library of instructional materials), CUNY Academic Works (the institutional repository), and Manifold (a collaborative publishing platform). Stacy suggested that Jennifer explore OER Commons because it is a tool where educators, including K-12 teachers and higher education faculty, share educational open content. After reviewing the tool, Jennifer decided that this would be beneficial for her teaching candidates for a number of reasons. First, OER Commons already had a plethora of open content available for K-12 educators. Therefore, the teaching candidates would be able to create new content or revise, adapt, or remix content currently in OER Commons. Additionally, the authoring tool within OER Commons provides flexibility when remixing content and includes editing tools similar to word processing software that is easy to use. Finally, introducing teaching candidates to a repository where they may develop habits to find and share resources also provides a pathway for the teaching candidates to continue to find, author, and remix open content in their own classrooms beyond the course. As we decided on the tool, Jennifer began to draft a description of the assignment, elaborating on the details of the assignment expectations and the tool to be used.

Considerations for Implementation

The collaborative partnership should consider institutional access to tools, authoring features provided in specific tools, their students’ digital literacy skills, and the time that faculty are willing to devote to developing students’ digital literacy skills, understanding of the tool, and understanding of OER within the course. With these factors in mind, the collaborative partnership explores the tools together to select one that meets the needs of the assignment, reaches the intended audience of the contribution, and will be manageable by the instructor and students within the course.

When exploring and evaluating possible tools and repositories, it is important to consider what students have access to and ensure that the intended audience will have access to the content. Often, the librarian is well-positioned to recommend relevant tools and repositories that align with the assignment goals, discipline, and/or intended audience of the artifact using prior conversations regarding the direction of the assignment. For example, if the artifact in a biology assignment is a test study guide meant to support other students who take the course in the future within that institution, the librarian may recommend that it go into cloud storage, such as a Google Drive folder, that could be shared with other students in the future. However, if the artifact in an art class is a textbook detailing specific techniques for anyone in the broader art community, the librarian may recommend that the instructor use WordPress or a Wiki-based collaborative publishing tool that is more widely accessible. These decisions are contextual based on access, relevance to the discipline, and intended audience.

Step 4: Design Intentional Negotiations for Openness

As we discussed the open tools and repositories, Stacy noted that students would need to consider and select a Creative Commons license for their work. Stacy and Jennifer discussed the nuances that faculty and librarians need to plan for in designing renewable assignments. The question posed by Wiley and Hilton (2018) to determine if an assignment is renewable asks if students are invited to share their work openly. We felt that being “invited,” as opposed to being mandated or directed, was an important piece for students, especially considering Cronin’s (2017) discussion of openness which is more fully explained below. We discussed how students may not want to share their work openly or publicly and needed an option to share with the class without sharing with the world. The class assignment involves sharing the artifact within a class folder in Google Drive and then sharing through OER Commons (see Appendix B for examples of openly licensed resulting student work). This provides options for students to consider if they want to openly share work with a teaching community, and, if so, whom they will share with (class community or global community), whom they will share as (their personal digital identity as a student or as a teacher), and if they will share this particular artifact within OER Commons.

Once students determined how they wanted to balance their privacy with openness, we realized that they would need to understand Creative Commons licensing. One feature of OER Commons is that the licenses are built into the authoring tool. On the submission page, users are asked to select a license to define how others might use their work. The form asks if they want to allow modifications (“yes,” “no,” or “yes, as long as others share alike”) and if they will allow commercial uses. The symbols associated with the Creative Commons licenses are not visible, and the explanation does not use jargon. Despite the ease of attributing a Creative Commons license within OER Commons, Jennifer still addressed open licensing directly with her class. We felt it was appropriate for the teaching candidates to spend class time understanding the licenses since teachers should understand copyright, fair use, and open licensing. Therefore, Jennifer assigned the students readings about OER. We also devoted one class session to instruction, discussion, and activities related to Creative Commons licensing and exploring OER offerings on OER Commons (the tool we selected for the renewable assignment). Subsequent class discussions revolved around licensing choices for their own work and evaluation of OER available to K-12 teachers.

Considerations for Implementation

Because open pedagogy is designed to empower students as creators, they need agency in making the decision to share openly and, if they choose to share openly, determining how they will share their work under a Creative Commons license. According to Cronin (2017, p. 18), openness is always “complex, personal, contextual, and continually negotiated” since there is a certain level of risk associated with sharing work. Balancing privacy considerations and open sharing is a critical consideration, as explained through the lenses of Cronin’s (2018) macro (global), meso (community/network), micro (individual), and nano (interaction) levels. At the macro level, students must first decide if they want to become part of an open network and contribute to this network by sharing open content (Cronin, 2018). Those who place a high priority on privacy may decide not to engage in open practices. Those who do engage in open practices must make key decisions. At the meso level, students should consider with whom they are willing to share their work (e.g., friends, the class, the professional community, the world, etc.), while they also decide with whom they will share at the micro level. This is a vital decision as students develop their digital identities and balance their private versus professional identities. Finally, once students have made these key decisions about open practices, they must then negotiate decisions about sharing the particular artifact they have developed as part of the renewable assignment (Cronin, 2018). In developing a renewable assignment, the librarian should help the instructor consider issues of student privacy and design options for students who opt out of sharing their artifact openly.

Another consideration in designing renewable assignments is how to develop students’ knowledge of Creative Commons licenses. It should not be assumed that faculty engaging in open practices and students entering courses fully understand the ramifications of different licenses. Therefore, while designing the renewable assignment, the librarian may support the instructor in fully understanding each of the licenses and what it means for student work as well as how to incorporate instruction of these ideas into the course. The instructor may explicitly teach a class about Creative Commons licensing, or address this more implicitly by helping students identify the symbols on open content they engage with during the course and lead discussions about what they mean before having students create their artifact. Alternatively, the librarian may be invited as a guest instructor to lead a lesson on Creative Commons licensing. While these decisions may certainly be made after the renewable assignment is developed, it is a good idea to start this conversation during the assignment design.

Step 5: Finalize and Reclassify Assignment

Throughout each of the previous steps, Stacy and Jennifer brainstormed ideas and clarified details of the assignment. Once the details were thoughtfully determined, Jennifer finalized the assignment description and wrote the rubric (see Appendix A). Afterwards, she shared the finalized assignment with Stacy, who first read through the description and rubric independently. As she read through it, Stacy applied a student lens in understanding the assignment and expectations, asking clarifying questions to ensure clarity. Afterwards, Stacy and Jennifer met together for one final meeting to reclassify the redesigned assignment using Wiley and Hilton’s (2018) four-part test introduced in step one. The discussion concluded that the final redesigned assignment description and rubric could indeed be classified as renewable since the teaching candidates are invited to use an open license to publicly share a new or revised/remixed OER artifact that has value to others beyond what the author learns in creating the artifact.

Considerations for Implementation

While this step is fairly straightforward, this is where the collaborative partnership between the librarian and faculty member reaches its peak. The librarian not only serves as a reviewer of the redesigned assignment, offering critical feedback to support the development of the description, but also reengages the faculty in reflective discussions. As the librarian and faculty member reclassify the assignment to ensure it meets the criteria of a renewable assignment, the partners may engage in dialogue to reflect on the value of the assignment to the field, the effectiveness of the tools utilized, and the match between the assignment’s learning outcomes and the learning goals of the course.

Conclusion

This chapter outlines a Renewable Assignment Design Framework for analyzing an assignment and adapting it to become renewable. This framework is meant to be used flexibly and can be adapted as needed in other situations or contexts. For example, the framework may be used in K-12 settings by collaborative teams of school librarians and teachers. Alternatively, teams of faculty members who want to rework a course may also use the framework as they reconsider the major assignments. Overall, it may apply in any context where assignments are being developed since students are asked to create artifacts in nearly every assignment. Far too often, students’ work exists only within the teacher-student relationship and is not designed for a broad impact. By discussing our experience and collaboration, we provide an example and path forward in utilizing Wiley and Hilton’s (2018) criteria to develop renewable assignments through our Renewable Assignment Design Framework. These design considerations for faculty and librarians assist in developing meaningful renewable assignments by outlining a collaborative process honoring the expertise and experience held by each, while the resulting artifacts provide evidence of empowered students who created open content.

References

Amaral, J. (2018). From textbook affordability to transformative pedagogy: Growing an OER community. In Wesolek, A., Lashley, J., & Langley, A. (Eds.) OER: A field guide for academic librarians (pp. 51-71). https://commons.pacificu.edu/pup/3.

Brandle, S., Katz, S., Hays, A., Beth, A., Cooney, C., DiSanto, J., Miles, L., & Morrison, A. (2019). But what do the students think: Results of the CUNY cross-campus zero-textbook cost student survey. Open Praxis, 11(1), 85-101. http://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.11.1.932

Chen, B. 2018. Foster meaningful learning with renewable assignments. In Chen, B., deNoyelles, A., & Thompson, K. (Eds.), Teaching Online Pedagogical Repository. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida Center for Distributed Learning. https://topr.online.ucf.edu/r_1h7ucljsasbkbsd

City University of New York. (2018). New York State Open Educational Resources funds CUNY year one report. http://www2.cuny.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/page-assets/libraries/open-educational-resources/CUNY_OER_Report_-_Web_-_Accessible-1.pdf

City University of New York. (n.d.). NYS OER Scale Up Initiative. https://www2.cuny.edu/libraries/open-educational-resources/nys-oer-scale-up-initiative/

Cronin, C. (2017). Open education, open questions. Educause Review, 52(6), 11-20. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/10/open-education-open-questions.

Cronin, C. (2018). Balancing privacy and openness, using a lens of contextual integrity. In Bajić, M., Dohn, N.B., de Laat, M., Jandrić, P., & Ryberg, T. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Networked Learning (pp. 288-292). http://www.networkedlearningconference.org.uk/abstracts/papers/cronin_33.pdf

CUNY Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. (2017). A profile of undergraduates at CUNY senior and community colleges: Fall 2017. http://www2.cuny.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/page-assets/about/administration/offices/oira/institutional/data/current-student-data-book-by-subject/ug_student_profile_f17.pdf

DeRosa, R. (2016, May 18) My open textbook: Pedagogy and practice. actualham: The professional hub for Robin DeRosa. http://robinderosa.net/uncategorized/my-open-textbook-pedagogy-and-practice/

DeRosa, R., & Jhangiani, R. (2017). Open pedagogy. In Mays, E. (Ed.), A guide to making open textbooks with students (pp. 7-20). https://press.rebus.community/makingopentextbookswithstudents/chapter/open-pedagogy/

DeRosa, R. & Robison, S. (2017). From OER to open pedagogy: Harnessing the power of open. In Jhangiani R. & Biswas-Diener R. (Eds.), Open. Ubiquity Press. http://doi.org/10.5334/bbc.i

Greenhow, C., Robelia, B., & Hughes, J. (2009). Learning, teaching, and scholarship in a digital age: Web 2.0 and classroom research: What path should we take now? Educational Researcher, 38(4), 233–245. http://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09336671

Grimaldi, P.J., Mallick, D., Waters, A.E., and Baraniuk, R.G. (2019) Do open educational resources improve student learning? Implications of the access hypothesis? PLoS ONE 14(3): e0212508. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212508

Hilton III, J. L., Robinson, T. J., Wiley, D., & Ackerman, J. D. (2014). Cost-savings achieved in two semesters through the adoption of open educational resources. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2). http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1700.

Ikahihifo, T. K., Spring, K. J., Rosecrans, J., & Watson, J. (2017). Assessing the savings from open educational resources on student academic goals. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(7). http://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i7.2754

Jhangiani, R. (2018, March 16). Why have students answer questions when they can write them? Open Pedagogy Notebook. https://openpedagogy.org/assignment/why-have-students-answer-questions-when-they-can-write-them-by-rajiv-jhangiani/

Katz, S. (2019). Leveraging library expertise in support of institutional goals: A case study of an OER initiative at Lehman College. New Review of Academic Librarianship. Advanced online publication. http://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2019.1630655

Kimmons, R. (2016). Expansive openness in teacher practice. Teachers College Record, 118, 1-34.

Lee, G.V., & Barnett, B.G. (1994). Using reflective questioning to promote collaborative dialogue. Journal of Staff Development, 15(1), 16-21.

Montgomery, J. & Leonard, A. (2015). LIB2205ARCH2205 Learning Places, FA2015. https://openlab.citytech.cuny.edu/leonardmontgomerylib2205arch2205fa2015/

Rosen, J.R. & Smale, M.A. (2015, January 7). Open digital pedagogy=critical pedagogy. Hybrid pedagogy. http://hybridpedagogy.org/open-digital-pedagogy-critical-pedagogy/.

Sapire, I., & Reed, Y. (2011). Collaborative design and use of open educational resources: A case study of a mathematics teacher education project in South Africa. Distance Education, 32(2), 195-211. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01587919.2011.584847

Veletsianos, G., & Kimmons, R. (2012). Assumptions and challenges of open scholarship. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(4), 166-189. http://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i4.1313

Wiley, D., & Hilton III, J.L. (2018). Defining OER-enabled pedagogy. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(4). http://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i4.3601

Contact Information

Author Stacy Katz may be contacted at stacy.katz@lehman.cuny.edu.

Feedback, suggestions, or conversation about this chapter may be shared via our Rebus Community Discussion Page.

Appendix A

Original Assignment

Inquiry Unit Plan

In a small group of two to four students, you will collectively choose a topic and design an inquiry or problem-based unit plan for a specific grade level. Within the unit, you must include different types of texts for students to analyze and mini lessons that guide students in this analysis. For example, you may include mini lessons that show students how to effectively generate key words to find information on their topic. In addition, you should include ways to differentiate lessons for individual learners such as struggling readers, ELL students, and students with learning disabilities. Your unit plan should detail a performance task that students would complete to conclude the unit or as a product of the unit. Be sure to include a rubric or other method of assessing this student work. A template will be provided to assist in the design of the unit.

Redesigned Renewable Assignment

OER Technology Integration Project

For the culminating assignment in this course, you will design, adapt, or remix an OER to share on OER Commons (https://www.oercommons.org/), then implement it in your classroom. You can design your project from scratch, adapt your project from existing work in your classroom, or adapt, remake, or remix an OER that already exists on OER Commons or in EDR 529’s shared resource collection on Google Docs. After designing, adapting, remaking, or remixing your OER resource, you are required to upload it into EDR 529’s shared resource collection and onto OER Commons using the resource or lesson builder. If you do not wish to share your work openly, please discuss this with your instructor. When you submit your work to Blackboard, you should include a link to the resource on OER Commons. Before you begin working on this project, have the instructor approve your idea.

Your project should creatively demonstrate how to integrate technology/new literacies into your classroom to support literacy learning in meaningful ways as a result of what you learned during this course. In addition, your project should exhibit your understanding of the skills students need to be successful in the 21st century and create experiences for students that utilize best instructional practices for integrating these skills into instruction. For example, your project may demonstrate how you empower learners to actively create, collaborate, and/or design. Be sure to include the grade level and specific standards that were addressed in your project.

You should plan to implement all or part of your project with your students and provide a two- to three-page reflection on the implementation. As appropriate, include samples of student work within your reflection and explain how implementation went. Note the students’ response, your own successes, students’ successes, challenges, and ways you might change the design in the future. Most importantly, detail a few lessons you learned about technology integration within the literacy classroom. Throughout your reflection, as appropriate, be sure to make connections to class texts. **Student work samples and your reflection should NOT be submitted to EDR 529’s shared resource collection or OER Commons. Rather, you will submit this through Blackboard.**

Ultimately, this project could take many varied forms, so be creative! In designing your project, you should use the ideas we have discussed in class, instructional strategies from your self-selected book, technology integration ideas from our texts, etc. to guide your project. Some ideas are:

- A module that includes multimodal resources for a unit of instruction, with plans to support their use in the unit and resulting evidence of student use

- An open book chapter for your students with multimodal texts on a given topic

- A series of lesson plans (or a unit plan) with examples of student work

- An inquiry unit with a digital performance task embedded and different modes of text used within the unit with examples of student work

- A collection of technological resources with mini lessons on how/when to use them and examples of student work after implementation of the resources

- Exemplar models of projects you completed with students along with student attempts

- Yearlong plan of how you will integrate a specific technological resource into your classroom with evidence of beginning stages of implementation

|

Component |

Beginning |

Developing |

Proficient |

Exemplary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Project Design

|

Does not appropriately embed learning activities with new literacies; does not align with standards (Substitution & Augmentation) Uses limited digital tools and resources to encourage learning that may not be active or deep Applies few to no instructional design principles to create a digital environment that minimally supports learning |

Demonstrates how to embed learning activities with new literacies that are inauthentic and may loosely align with standards (Substitution & Augmentation) Uses minimal digital tools and resources to encourage learning that may not be active or deep Applies some instructional design principles to create a digital environment that mostly supports learning |

Demonstrates how to embed authentic learning activities with new literacies that align with standards (Augmentation, Modification, & Redefinition) Uses some digital tools and resources to encourage active, deep learning Applies instructional design principles to create a digital learning environment that supports learning

|

Demonstrates how to embed creative and meaningful authentic learning activities with new literacies that align with standards (Modification & Redefinition) Uses varied digital tools and resources to maximize active, deep learning Applies effective instructional design principles to create an innovative digital learning environment that engages and supports learning |

|

Student Skills

|

Does not model/nurture students’ creativity when communicating ideas, knowledge, or connections Provide little to no support for students’ use of technology Demonstrates little to no understanding of 21st century skills and literacy demands required of students

|

Allows for minimal student creative expression to communication ideas, knowledge, or connections Supports students’ use of technology with various approaches that may not be appropriate Demonstrates limited understanding of the 21st century skills and literacy demands required of students

|

Models/nurtures some student creative expression to communicate ideas, knowledge, or connections Appropriately supports students’ use of technology with scaffolded approaches Demonstrates an adequate understanding of 21st century skills and literacy demands required of students

|

Models/nurtures student creative expression to communicate ideas, knowledge, or connections Effectively and appropriately supports students’ use of technology with scaffolded approaches appropriate for student age Demonstrates an exemplary understanding of 21st century skills and literacy demands required of students |

|

Reflection

|

Little to no implementation of the project design Provides an outline of the project implementation with little to no reflection Provides limited to no examples of student work; makes few to no connections to course content; does not provide lessons learned that are not applicable to future technology integration efforts

|

Bare implementation of the project design Provides a limited reflection on the project design and implementation; feels more like a report of the events than a reflection Provides few examples of student work (does not necessarily need to be within the reflection) Makes limited connections to course content to provide general or vague lessons learned; lessons learned may not be applicable to future technology integration efforts

|

Implements all of or a sufficient portion of the project design Reflects on the project design and implementation, including some specific responses, comments, and reactions Provides examples of student work (does not necessarily need to be within the reflection) and uses these examples to make points in the reflection Makes connections to course content in order to provide broad lessons learned that may guide future technology integration efforts

|

Implements all of or a significant portion of the project design Thoughtfully reflects on the project design and implementation, including specific responses, comments, and reactions Provides multiple examples of student work (does not necessarily need to be within the reflection) and uses these examples to make salient points in the reflection Thoughtfully makes connections to course content in order to provide a few broad lessons learned that can be applied to future technology integration efforts |

|

Mechanics and References

|

Many grammatical and spelling errors that distract from meaning In-text citations and references do not adhere to APA format |

Some grammatical and spelling errors that distract from meaning Many in-text citations and references do not adhere to APA format |

Few grammatical and spelling errors that do not distract from meaning Most in-text citations and references adhere to APA format

|

Little to no grammatical and spelling errors All in-text citations and references adhere to APA format

|

Appendix B

Links to Resulting Candidate Work

Work Shared on Google Drive with a Creative Commons License

- Addition and Subtraction Book Chapter – 1st Grade

- Licensed CC-BY-NC

- Interviewing Characters in Because of Winn Dixie Project – 4th Grade

- Licensed CC-BY-SA

Work Shared on OER Commons with a Creative Commons License

- Ocean Garbage Patches Unit – 5th grade

- Licensed CC-BY-NC-SA

A student-centered teaching approach that empowers students as creators of knowledge and open resources.

A process to develop renewable assignments.

An assignment or activity in which students are invited to openly license and publicly share the artifact that is created, which has value beyond the students' own learning.

A copyright license that allows for free distribution of the work. Different types of Creative Commons licensing indicate whether the work can be freely distributed, modified, or used commercially, and what attributions are required for redistribution of the original or adapted work.