Part III: Latin America

Serena Cosgrove and Ana Marina Tzul Tzul

Introduction

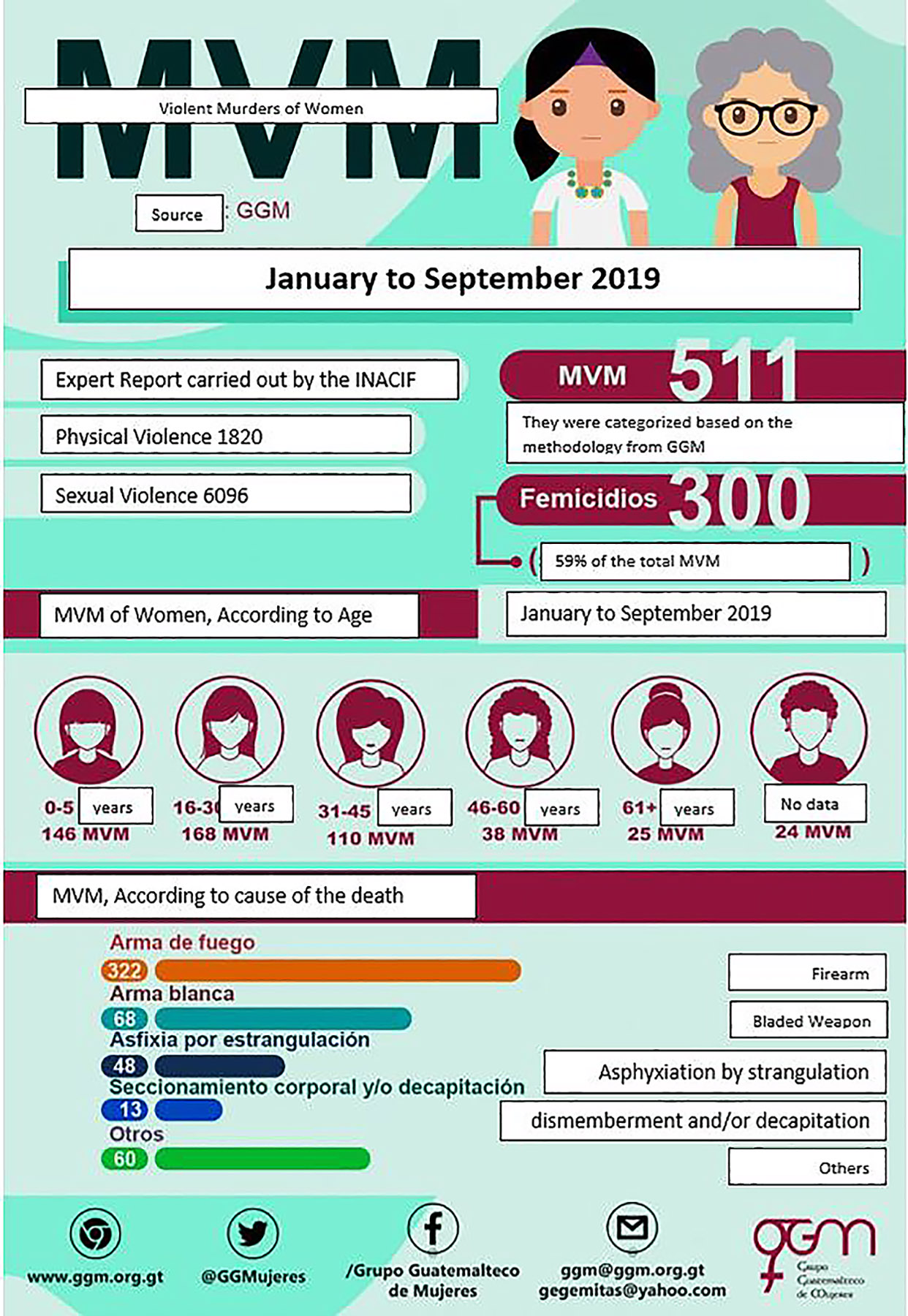

Inspired by the work of civil society women leaders in Guatemala, this profile focuses on the achievements and mutual support that connect the women’s organizations that belong to the Guatemalan Women’s Group (Grupo Guatemalteco de Mujeres, or GGM), an umbrella organization based in the capital Guatemala City. GGM’s mission is to support women’s organizations across the country, providing much-needed services to women survivors of gender-based violence.

History

Many argue that there are multiple historical events in Guatemala—Spanish colonization, early statehood consolidation and the emergence of political and economic elites, and the thirty-six-year civil war (1960–1996)—that contribute to today’s high levels of gender-based violence (see Carey and Torres 2010, Sanford 2008, and Nolin Hanlon and Shankar 2000). Gender-based violence is defined as “any act that results in, or is likely to result in physical, sexual, or psychological hard or suffering to women [and people with non-dominant gender identities and sexualities], including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life” (Russo and Pirlott 2006, 181). There are also a number of current social factors such as inequality, poverty, and discrimination due to gender and ethnicity as well as high levels of violence due to insecurity, gangs, and drug trafficking—that contribute to the “normalization” of gender-based violence in the private, domestic sphere, as well as in the public sphere.

The countries with the highest femicide rates in Latin America are El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala (Gender Equality Observatory 2018). Femicide is the killing of a woman because of her gender; it is an extreme example of gender-based violence, which is on the rise according to Musalo and Bookey (2014, 107) and Cosgrove and Lee (2015, 309). From 2000 to 2019, 11,519 women were violently killed in Guatemala (GGM 2019); the rate of violent deaths of women is growing faster than homicide levels (though homicide rates remain higher than femicide rates). In 2018 alone, 661 women were killed violently in Guatemala (GGM 2019). In fact, violence against women is one of the most highly reported crimes in Guatemala, yet impunity rates are also abysmally high: only 3.46 percent of cases presented between 2008 and 2017 were resolved according to the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG, 9).

Organizational History and Mission

The Guatemalan Women’s Group (GGM) was officially founded in 1988, and in 1991, they opened their first Center for Integrated Support for Women (or CAIMUS) in Guatemala City with the goal of providing an integrated package of services to women survivors in the capital. Today, GGM is an umbrella organization that oversees 10 CAIMUS across the country (with four new organizations coming onboard).

In its early years, GGM played a leadership role at the national level convening diverse women’s organizations across the country to assure that women’s voices were being heard in the peace process and in the early implementation of the peace accords in post–civil war Guatemala. GGM encouraged women to talk to each other from across the country, and this contributed to bridging the class divide between feminists in the capital and women committed to women’s issues from across the country. GGM also played an important role in the No Violence against Women Network, which brought together organizations around the country actively working to eradicate gender-based violence locally and to lobby for improved laws and public-sector accountability at the national level.

This activism by women led to the law against gender-based violence being passed in 1996, as well as the 2008 law against femicide and other forms of violence against women. These laws, in turn, pressured the government to form a public sector–civil society commission to promote state accountability and collaboration with women’s organizations. However, the government has never fully supported GGM or their goals. In 2018, the government only provided a small percentage of funding it had promised to the CAIMUS for their functioning. In 2019, the CAIMUS weren’t even included in the national budget, a sign that the government’s commitment to addressing gender-based violence is waning.

Today GGM provides oversight, training, and fundraising for the CAIMUS, which use the GGM model of integrated services for women survivors including social, medical, psychological, and legal services as well as access to women’s shelters. In addition to seeking resources for CAIMUS and creating a space for mutual support in a struggle that often feels overwhelming, GGM is also a think tank and advocacy organization gathering and analyzing data about the rates of violence against women and leading public campaigns to change the perceptions of Guatemalans about violence against women. Always in coordination with other organizations and social movements across the country, GGM uses key dates for women’s liberation—such as March 8, the International Women’s Day, or May 28, International Day of Action for Women’s Health, among other dates—to organize national campaigns to raise awareness about women’s rights, gender-based violence, and related issues. These campaigns use billboards and other opportunities for public outreach such as radio spots, social media, and events and programming to spread their message. See GGM’s website for more information: http://ggm.org.gt/.

Leadership

The founder and director of GGM is Giovana Lemus. Her story embodies sacrifice and commitment to women’s participation and contributions to society from before the war ended in 1996, and yet it is also about one-on-one accompaniment of women leaders. As a college student during the civil war, Giovana observed many cases of injustice and violence; she saw how these affected Indigenous people, women, and the poor across the country. In the 1980s she joined other concerned women who all banded together across different backgrounds to serve as peace builders. The importance of working with women showed Giovana how valuable it is to open space for women to support each other and their contributions. Giovana’s own childhood experiences also contributed to her activism. Her mother always welcomed survivors of gender-based violence into the home, making sure it was a safe haven for them. When Giovana’s mother died, Giovana had the example of her nine older sisters to inspire her, as well as her father who always encouraged her to speak her truth and make a difference.

Giovana sums up the important role that promoting women’s leadership can play and that women can build impact through coordinated action: “It is a concrete inspiration to carry out actions and achieve [our goals]” (Interview by author, July 2, 2013). Recently Giovana said, “Our sisterhood grows stronger because of what we’ve had to face” (Interview by author, July 30, 2019). The word that repeatedly appears in our interviews with Giovana and the directors of the CAIMUS when discussing GGM’s role is acompañar (to accompany). And even though there are so many challenges, Giovanna remains optimistic: “We are making progress” (interview by author, July 2, 2013). Giovana’s support of the directors of the CAIMUS has played a significant role in getting more CAIMUS established. The directors speak warmly of the guidance and support they have received from Giovana.

Summary

Though Guatemala is often considered to be a difficult place to be a woman, it is also a country where women themselves are working together to address and transform the problem of violence by collaborating across multiple sites and levels. GGM and its member organizations often face direct government hostility, public-sector resistance in providing promised funding, and a climate in which it is increasingly difficult to raise funds for their work. This creates a double fight: the struggle to end gender-based violence and the fight for state funds to do their work. GGM remains committed to tackling both of these ongoing challenges.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of our institutions—Seattle University and Universidad Rafael Landívar—and we are inspired daily by the example of all the women activists of Latin America and the Caribbean who are making inclusive, social change happen across the region.

Bibliography

Carey, David, and M. Gabriela Torres. 2010. “Precursors to Femicide: Guatemalan women in a Vortex of Violence.” Latin American Research Review 45, no. 3: 142–164.

Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (CICIG). 2019. “Diálogos por el fortalecimiento de la justicia y el combate a la impunidad en Guatemala.” Report can be found on CICIG website. https://www.cicig.org/comunicados-2019-c/informe-dialogos-por-el-fortalecimiento-de-la-justicia/. Accessed August 12, 2019.

Cosgrove, Serena, and Kristi Lee. 2015. “Persistence and Resistance: Women’s Leadership and Ending Gender-Based Violence in Guatemala.” Seattle Journal for Social Justice 14, no. 2: 309–332.

Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2018. “Femicide, the Most Extreme Expression of Violence against Women.” Oig.cepal (website). https://oig.cepal.org/sites/default/files/nota_27_eng.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2019.

Grupo Guatemalteco de Mujeres (GGM). 2019. “Datos estadísticos: Muertes Violentas de Mujeres-MVM y República de Guatemala ACTUALIZADO (20/05/19).” GGM (website). http://ggm.org.gt/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Datos-Estad%C3%ADsticos-MVM-ACTUALIZADO-20-DE-MAYO-DE-2019.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2019.

Musalo, Karen, and Blaine Bookey. 2014. “Crimes without Punishment: An Update on Violence against Women and Impunity in Guatemala.” Social Justice 40, no. 4: 106–117.

Nolin Hanlon, Catherine, and Finola Shankar. 2000. “Gendered Spaces of Terror and Assault: The Testimonio of REMHI and the Commission for Historical Clarification in Guatemala.” Gender, Place & Culture 7, no. 3: 265–286.

Russo, Nancy Felipe, and Angela Pirlott, A. 2006. “Gender-based Violence: Concepts, Methods, and Findings.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1087: 178–205.

Sanford, Victoria. 2008. “From Genocide to Feminicide: Impunity and Human Rights in Twenty-First Century Guatemala.” Journal of Human Rights 7: 104–122.