Part II: South Asia

Ina Goel

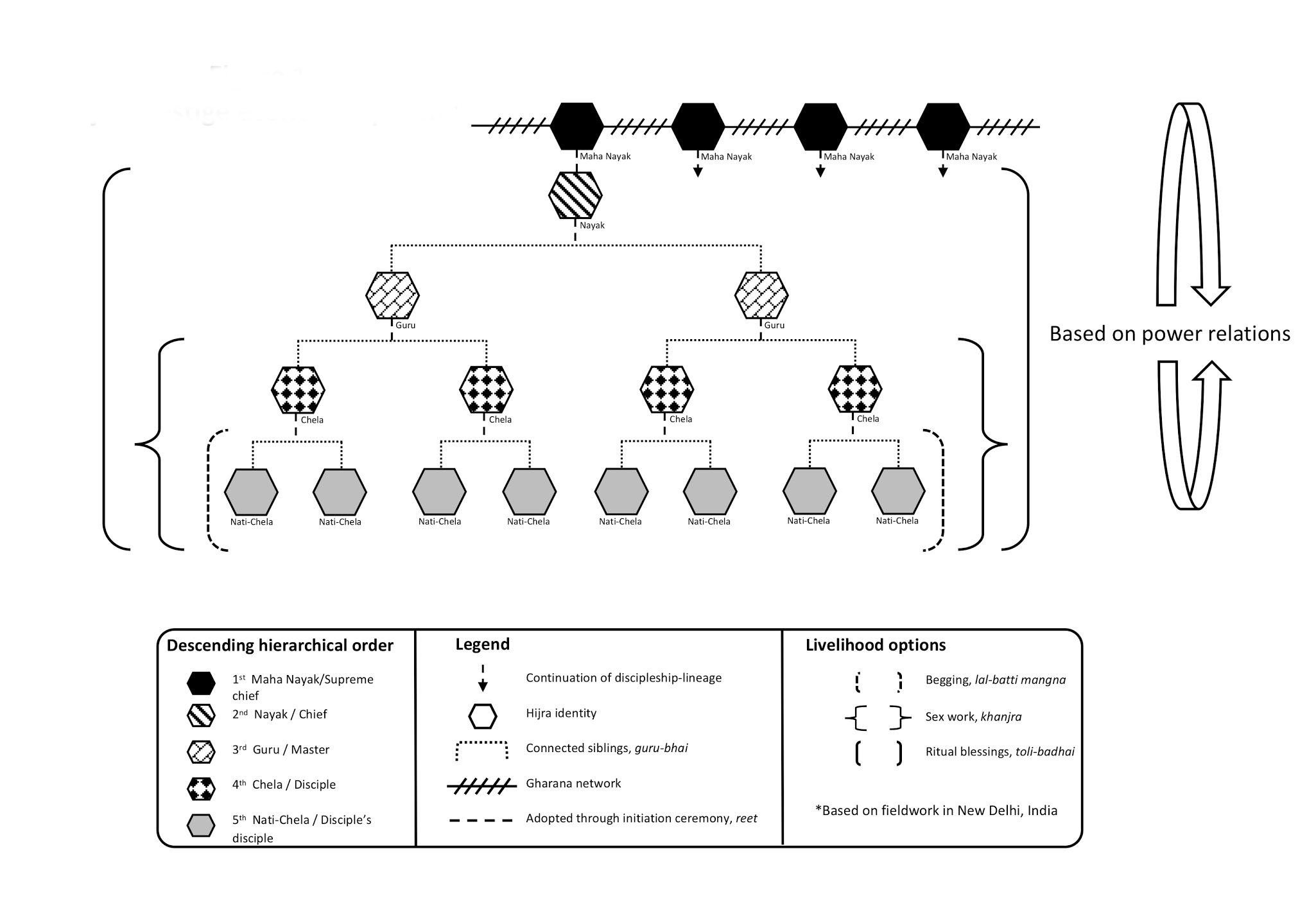

In this chapter, the author looks at the organization and functions of a third-gender group in India: the hijras. Here we see how hierarchy and caste also shape third-gender hijra communities. These communities create and operate through discipleship-kinship systems that both regulate their activities and create a power structure among the hijras. These kinship systems are not recognized and legitimized by the Indian state but by the internal hijra governance councils.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter students should be able to

- Define the hijras, a “third” gender community in India.

- Describe the pattern and complexity of hijra kinship.

- Explain the hijra prestige economy system.

Sharmili, a twenty-four-year-old hijra from the Dakshinpuri area in New Delhi confided in me that she belongs to the Valmiki community. In north India, the Valmikis are classified as a subcategory of caste belonging to the Dalit community. Indian kinship is always grouped around a system of social stratification based on birth status known as the caste system, and the Dalits are a historically oppressed caste, formerly known as “untouchables” in India. Most people in Sharmili’s natal family work as safai karamcharis, or sanitation workers, a job that is socially bound to those in the lowest castes in India. Sharmili’s maternal grandmother worked as a safai karamchari at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, where I completed my MPhil studies in social medicine and community health. Sharmili inherited this job from one of her dying relatives, her maternal uncle, and worked at a national bank in New Delhi as a safai karamchari. The passing down of sanitation work from one generation to another within the Valmiki community is made possible because of a government policy that enables safai karamcharis to nominate a member of their family to take up the same line of work after their death (Salve et al. 2017).

When Sharmili started her job at a local branch of one of the world’s biggest banking corporations (in which even I have an account), Sharmili was still using her deadname. Arriving at work every day on a motorcycle, Sharmili used to wear a black leather jacket and had an outwardly masculine appearance. Based on the belief that people’s gender is fixed for life, Sharmili’s colleagues at the bank assumed that her then “alpha-male” persona was set in stone. So much so that when Sharmili started showing visible signs of becoming herself by growing her hair and wearing light makeup to work, other colleagues at the bank did not like it. They did not even consider that Sharmili was inwardly always feminine, and when they saw her displaying those traits outwardly, the colleagues at work started making fun of her new effeminate look.

The ongoing teasing at work made Sharmili believe that at least she was being recognized for who she really is, even if that came at a cost. In those taunts, Sharmili found recognition of a gender identity she always thought she belonged to. Mustering courage, Sharmili showed up at work in a salwar-kameez, a traditional style of clothing typically worn by women in north India, coordinating her outfit with a dark color shade of lipstick and a long scarf called a dupatta. It was on this day, as she clearly remembers, that one of her colleagues pulled at her dupatta to shame her for “acting” like a female. Since then, pulling at Sharmili’s dupatta became an office joke that was quickly shared and spread among some of her male colleagues. Sharmili felt violated. Even though they were colleagues, Sharmili felt “lower” than them in social status, not only because of caste but also because of her transgender identity. Sharmili’s colleagues continued to bully her.

Sharmili underestimated just how much a change in her attire would provoke reactions from her colleagues. They were now more open and outwardly bullying Sharmili by calling her derogatory names like chakka and gandu (asshole or giving ass) (Bhaskaran 2004, 95). The environment grew so hostile that Sharmili would end up crying in the bathroom at her place of work most of the time. Despite the harassment at her job, Sharmili continued to come to work because at that point this was the only means of income available to her natal joint-family.

One day, the bank manager and some senior colleagues gave Sharmili an ultimatum that if she wanted to continue her job as a safai karamchari, she must not dress as a woman and must return to her “male” disguise. Irrespective of Sharmili being the only breadwinner in her family, a fact known by the bank management, they considered it their duty to provide a “family-friendly environment,” which they thought was put at risk by Sharmili’s presence. Not only that, Sharmili was considered a “threat” by the bank management, especially to the women colleagues working there, and more so for the “female” customers and their accompanying children visiting the bank. The perceived threat to the bank’s image was based on the stereotype that “hijras” kidnap young boys and castrate them to increase the membership of their own community. Therefore, Sharmili’s presence in itself was considered a “bad influence” that was perceived as threatening to women working and visiting in the bank.

Not being in a position to negotiate her working relations with the bank management, Sharmili eventually decided to quit her job as a safai karamchari. During this distressing time, she came in contact with the hijra community living in her area. She was introduced to a hijra guru by her friend who was also her neighbor and the same person who loaned her the salwar-kameez.

The hijras are a third-gender group in India and can be understood as subaltern trans-queer identities existing within a prestige economy system of kinship networks. The hijra guru initiated Sharmili into the hijra community through a reet, or a ritualistic ceremony. In this ceremony, Sharmili was adopted by the guru to the hijra house or gharana to which the guru herself belonged; in this way, she became a new member of the house. It was during this process that the name Sharmili became the only name she wanted to identify with: she did not want to use her natal family surname, which also revealed her caste origins. Her hijra guru accepted Sharmili just as she wanted to be.

In her coming days of apprenticeship with the hijra guru, Sharmili learned the hijra ways of being. She learned how to dress, wear makeup, sing hijra traditional songs, and dance the steps that accompany those songs. Sharmili wanted to earn money through the “traditional” way of hijras, typically by collecting ritual blessings or toli-badhai where the hijras shower their blessings on newborns and newlyweds in exchange for gifts both in cash and kind. However, Sharmili’s hijra guru had other plans for her.

Despite Sharmili’s dancing skills and musical flair, her hijra guru did not allow her to be in the group for toli badhai. Instead, Sharmili was encouraged to work as a beggar and assist in begging at traffic signals, or lal-batti mangna. If Sharmili wanted to boost her income and earn extra, then she was also given the option for sex work, or khanjara, by her hijra contemporaries. Sharmili felt that it was because of her lower-caste status that her hijra guru did not allow her to be a part of the auspicious dances associated with collecting ritual blessings. Historically those coming from the Valmiki community have been denied priestly jobs and even barred by the upper castes from entering temples for the fear that lower castes will “pollute” the sacredness of those spaces.

Sharmili felt fortunate to be accepted by her hijra guru for her chosen gender identity but also felt discriminated against due to her caste identity. Eventually, Sharmili made contacts in another hijra group, in the Trilokpuri area of New Delhi that let her accompany them in their group for toli badhai. Sharmili now commutes four hours’ round trip on a public bus whenever she can from Dakshinpuri to Trilokpuri just to be able to earn respect and money in traditional hijra performances.

Understanding Hijras

Distinct from transgender and intersex identities in other countries, hijras occupy a unique and contradictory place in Indian society. Many have understood “third gender” to mean only the hijras; however, numerous other gender nonconforming identities fall under this umbrella term—and yet, some argue against the use of the term “third” gender for all gender nonconforming people.

One of the main differences between trans and hijra identities is that trans people have the freedom to self-identify as trans. To identify as hijra, a person must be initiated through a ritual adoption by a hijra guru into the hijra community (see Nanda 1990 and Reddy 2006). The general trans population in India does not adhere to such an internal social system but subsequently has a less tight-knit community than hijras. Also, conventionally, trans men are not a part of the hijra community.

Legally recognized as the “third” gender in April 2014 by the Supreme Court of India, the hijras are a highly stigmatized minority group with an estimated population of half a million according to the Census of India 2011 (Census of India 2011). However, this figure is widely disputed as the census counted trans people, the hijras, and intersex births under the third-gender category. Therefore, the population counted by the census is not a true representation of hijra demographics in India. In 2018 India also decriminalized homosexual sex, overturning a 160-year-old law instituted by the British.

One explanation for this confusion over the differences between other third-gender identities, transgender persons, and those born intersex could be that the Hindi word hijra has been used as a catchall term for all these identities. Moreover, the interchangeability of the term hijra with the terms such as transgender and intersex neglects the historicity of all these three terms that came about in different contexts and sociopolitical settings, and conflating them is problematic.

There is also an inherent public confusion persisting in understanding who hijras are and who they are not. Addressing this confusion are classifications made by the hijra communities themselves on who “real” hijras are and how they are differentiated from those who are “fake.” One such way to demarcate the difference between the two is by affiliation to a hijra “house.” “Real” hijras have a house affiliation whereas “fake” hijras do not have this affiliation. “Fake” hijras are men who are “cross-dressed beggars” and not “legitimate hijras but are often mistaken as having a hijra identity by the “mainstream public” (Dutta 2012, 838). In India, an authentic hijra identity is based on its affiliation to a hijra gharana (house society) (see Goel 2016). The hijra gharanas are symbolic units of lineage, called a house, guiding the overall schematic outlining of the social organization of the hijra community in India.

In this chapter, I will focus on two areas to help understand the ties between gender and kinship in the hijra community in India. I have been working with the hijras for over ten years, first as a social worker and then as an anthropologist witnessing their struggles and successes. I learned to speak Hijra Farsi and was ritually adopted into the community by a guru. The first section of this chapter will highlight the historical roots of the formation of a kinship system within the hijra community and its connection to the contemporary forms of kinship. The second section will focus on the prestige economy system of the hijra community and the various ranks within it. The overall aim is to enable readers to understand the complex multilayered hierarchies and intersectionality between gender and kinship within the hijra community in India.

Hijra Kinship

The Historical Lens

In the seventeenth century, eunuchs became trusted servants in the Mughal courts. The term eunuch in reference to hijras in India is now considered pejorative; however, historical research finds the terms eunuch and hijra used interchangeably. Through their gender “uniqueness,” the eunuchs were allowed to travel freely between the mardana (men’s side) and the zenana (women’s side), guard the women of the harems, and care for their children (Jaffrey 1996, 53). Travelogues document that the eunuchs were also “intimate servants” and “beloved mistresses” of kings and princes (Jaffrey 1996, 54). The eunuch slaves had many different roles to play, and different tasks were assigned to them in royal courts (Taparia 2011). Eunuch slaves were not only in charge of administrative tasks but also served as confidantes, warriors, and advisors at the helm of diplomatic and military affairs. And in some rare instances they held literary posts in the imperial courts in New Delhi (Chatterjee 2000). However, because of their enslaved status, eunuchs could not establish a life elsewhere and were not allowed to leave the royal territories.

Historical evidence reveals that there were internal relationships among the court eunuchs themselves, like that of a master (guru) and disciple (chela) (Hinchy 2015). During the Mughal period, the court eunuchs in India were known as Khwaja Seras (Jaffrey 1996, 29). The word Khwaja Sera comes from Persian— “(Khwaja: honorific, meaning ‘real master’; sera, to decorate),” which reads as “male members of the royal household” decorating the real master (Jaffrey 1996, 29). In the mid-eighteenth century, nonbiological kinship relations were formed between child eunuchs and adult Khwaja Seras. Such relatedness was formed by a system of discipleship-lineage of the guru-chela relationship. It has been argued by Hinchy (2015, 382) that through this socially recognized kinship, the emotional impact of enslavement was lessened for the enslaved children. Though eunuch slavery has now long been a thing of the past, kinship based on relationships of discipleship among hijras by organizing themselves in households and societies remain central to the hijra community.

Discipleship-Lineage Bond

Hijra kinship works as a nonbinary family network, the continuation of which is based on a nonbiological discipleship-lineage system. Within the hijra community, members use Hindi kinship terms and

call one another nani (grandmother), dadnani (great grandmother), mausi (mother’s sister), didi (elder sister), gurumai (head of the [house] band), gurubhai (disciples of the same guru), chela (disciple), natichela (disciple of disciple) or amma or ma (mother). (Saxena 2011, 55)

Though most of the kin relation terms are addressed in the feminine pronoun, chela (which is lower in the hierarchy) and nati-chela (disciple of a disciple, lowest in the hierarchy) are addressed using male pronouns. Furthermore, all the disciples to the same guru are “brotherly” related to each other as another male pronoun of bhai (Hindi term for “brother”) is suffixed after guru to describe their relationship to each other.

There are some other aspects of kin relatedness that often appear to be contradictory to its gendered status within the hijra community. For instance, those hijras who share a common guru continue to be “brotherly” related to each other, even if they rise higher up in the hijra hierarchy. Therefore, they may be addressed as ma (or mother) by their disciples lower in rank but as “brothers” by those who share the same rank. The ambivalence of simultaneously using both male and female gendered pronouns for addressing the kin relatedness to the same person within hijra community creates a unique way to embrace the androgynous nature of hijra kinship.

There are also many descriptive ways and terminologies to identify the same kin relation within hijras. An example of multiple descriptive terms to refer to the bonding between two ranks of hijras—guru and chela—are teacher and student, master and disciple, husband and wife, mother and daughter, and mother-in-law and daughter-in-law, respectively. An example of how the affective bonds between gurus and chelas are formalized by the government of India is through voter ID cards. During fieldwork, I saw that hijras who had valid voter ID cards, listed “TG (transgender) or O (other)” as their gender, had the names of their gurus written in the column that required either their father’s or husband’s name. Yet, contradictorily, in December 2017, the police did not allow the hijra family of Bhavitha, who was found dead near a dustbin in the city of Warangal, to claim her dead body because their nonbiological kinship networks are not recognized by Indian law (Datta 2017). These examples show the Indian government’s ambivalence toward the recognition of hijra kinship in India.

Some scholars also believe that hijras lie “outside” stratification systems of caste in India because hijra kinship contrasts with heteronormative assumptions of family (Hall 2013, 635). Therefore, it is believed that the hijras “are not moderated by the logic of the caste system” (Reddy 2006, 145), and there is no apparent caste-based ritualistic practice to which the hijras collectively subscribe (Belkin 2008). However, Nanda (1990, 40) briefly mentions that hijra “houses” function as divisions between different hijra groups to facilitate intracommunity organization, replicating the patterns of the Indian caste system. When a hijra is adopted by a guru through a ritualistic ceremony, along with renouncing the perceived male gender assigned at birth, there is also a renunciation of the caste assigned at birth. As a result, I found that most hijras drop their surnames to hide their caste at birth identity. These dropped surnames are often associated with those caste identities that need hiding in order to protect them from caste-based discrimination in India (see Goel 2018). Other hijras who have higher caste privilege by birth often retain their surnames. In rare instances, newly initiated hijra chelas may also take the surnames of their hijra gurus. Therefore, in the hijra community, the core and the burden of maintaining the guru-chela relationship rests heavily upon the individuals where kin relatedness becomes highly “performative” (see Butler 2006). There are strict rules of kin performativity institutionalized in a hijra prestige economy system.

One of the crucial aspects of the hijra community is its social stratification embedded within a prestige economy system. With the hijra prestige economy system, kin relatedness is rooted in the social standing of hijras to one another. The social standing is based on a number of factors contingent on the power relations between and among different individual hijras and their gharana networks. There is no written constitution that the hijra gharanas have to abide by. There is, however, an ideal “expected” hijra behavior and unwritten rules to meet those expectations. This ideal of a “good” hijra, based on behavioral expectations and an unwritten code of conduct, is similar to how gender roles are imposed in any society—though always in the process of transition but often based on unspoken norms. There are three key aspects of performative kin relatedness within the hijra community: respect, livelihoods, and embodiment.

Respect

The hierarchical guru-chela relationship is the formative core of the social organization within the hijra community. Working with the hijras of Hyderabad, anthropologist Gayatri Reddy (2001, 96) has highlighted the importance of respect: “If there is no guru. . . in the hijra community, that person [from the community] does not have (honour/respect), and is not recognised as a hijra.” Furthermore, Reddy, in another study (2006, 151), argues that the hijra “affective bonds” of guru-disciple are “assigned [by the guru] rather than chosen” and are in contrast with the concept of “chosen families” described by Kath Weston (1991, 1998) in the context of American gay and lesbian relationships.

Based on my fieldwork, one of the many rules within this prestige economy system is the expectation that the chelas always speak in a pitch lower than their gurus and don’t interrupt or cross them while the gurus are speaking to others in public. If a chela does not obey this form of kin performativity, then a monetary fine or dand is imposed upon the chela by the guru for the infringement of this rule. The chela is not allowed to participate in the hijra activities or earn through their hijra networks until the dand is paid in full by the chela to the guru. Despite being in a symbiotic relationship, the gurus have more control over their chelas’ appearance and activities, which is consistent with hijra hierarchy. There are internal councils that serve as disciplinary bodies within the hijra community to guide the code of conduct of kin relatedness between the gurus and chelas. There is also a practice of pleasing their gurus as a kin-performative gesture because those who are close to their gurus often inherit the property from them after their death. Some examples include offering unconditional service (seva) like pressing and massaging the guru’s feet, which is always instrumental for becoming the guru’s “favourite” disciple. A hijra, Saloni in the Seelampur area of east Delhi, reflecting on the relationship with gurus, said that

sometimes the guru–chela relationship is as sweet as a mother-child relationship, but you know how it is these days. A majority is considered similar to that of a mother-in-law–daughter-in-law relationship, which is both sour and sweet at times. (Saloni, interview by author)

Within the prestige economy system, the upward mobility of hijras is also measured by the number of chelas the hijra gurus have under their patronage. Therefore, the more chelas a guru has, the more social status and respect the guru earns in the broader hijra community. This upward mobility then raises a hijra guru to the status of a hijra chief, or nayak within the larger community. The nayaks of the hijra community are often those who are financially better off, compared to the rest of the hijra kin under their patronage. Although the nayaks may not be directly involved with the day-to-day life activities of those chelas and nati-chelas under them, they often serve as mediators when there are disagreements between gurus and chelas as they serve on the hijra internal councils. Scholars have found that the hijra community is legitimized by these councils, also known as hijra jamaats or hijra panchayats, which are formed by an internal governing body comprising higher ranked members within the hijra community (Nanda 1990; Reddy 2006; Jaffrey 1996; Goel 2016).

Those hijras who have positive kin relations within the overall community, a large number of people in their gharana networks, and superior wealth and rank as compared to the rest of their hijra kin are then voted as greater chiefs, or maha nayaks of the community within the internal council of the hijras. These greater chiefs are mostly responsible for maintaining kin relations among different gharana networks of hijras within one state or across different states in India.

Those junior in rank have to seek permission from those in higher ranks to engage in activities outside of their hijra ways of life. This may include maintaining kin relations with their natal families or having sexual partners. Hijras’ participation in any research- or media-related activities must also be approved by someone higher in rank. The hijras therefore function as a closed social group, tied by their kin relatedness and guided by an internal council that helps to maintain the social order within their prestige economy system.

Livelihoods

Those hijras who are lowest in rank, like nati-chelas, are often assigned to work as beggars at traffic intersections and on public transportation to earn money. Begging is considered to be of the lowest prestige within the hijra community, so those engaged in begging are automatically considered to be lower in rank within the hijra hierarchy. Those in a higher rank have the power to delegate begging to those lower in rank and can choose not to participate in this activity. Those with a slightly higher rank (e.g., chelas) can also work as sex workers to boost their incomes.

However, those in the lower ranks find it challenging to be in sex work because often they do not have the financial resources to sustain their looks. For many lower-rank hijras, it is difficult for them to perform gender the way they would like to, due to the prohibitive costs of makeup, fine clothing, and body transformations. For example, those soliciting sex in cruising areas (often accessed by lower-rank hijras) earn only a pittance since they shave their faces, which leaves “unattractive” chin and jawline stubble. Those hijras (also higher in rank) who earn better money undergo laser hair removal from their faces and bodies, mammoplasty, and better hormonal injections that enhance their femininity—an aspect that is rewarded by the better-paying sex customers. Moreover, those hijras lower in rank also find it difficult to attract customers in some open cruising areas because of increasing competition from other “effeminate” men (or kotis) and female sex workers. Kalyani, a hijra who has not been castrated but has breast implants, said:

We hijras are well aware today of our health and the consequences that such an atrocious operation (castration ceremony) of removing the most sensitive and important part of our bodies can do. I am still a hijra and I do not want to harm my body permanently for the rest of my life. (Kalyani, interview by author)

Hijras higher in rank, like gurus, are often those delegating work assignments to the hijra ranks subordinate to them. The gurus have the privilege of choosing who will accompany them for ritual blessings, or toli badhai. The guru selects the chelas and nati-chelas based on several factors. These include their mutual cordial relationships, hijras with more money and better methods of “feminine” gender performativity, caste status, and sometimes just circumstantial luck. Ritual work is considered to be of the highest prestige within the hijra community. Therefore, those engaged in toli badhai are automatically considered to be higher in rank within the hijra hierarchy. However, it must be noted that collecting voluntary donations through ritual work is also an institutionalized form of begging—a traditional way of earning a livelihood within the hijra community.

Conventionally, the senior gurus do not engage in sex work openly or visit cruising areas to solicit prostitution. Within the hijra prestige economy system, it is considered disrespectful for gurus to take part in such activities. However, in some cases, the gurus might themselves be involved in sex work but only with a select client base. The chelas have to show respect to the guru by not acknowledging this aspect of their lives in public, despite it being a public secret.

However, before rising to the rank of a guru, the hijras almost always have to work as sex workers and beggars. Therefore, rising in rank within the hijra hierarchy of social systems also entitles the hijras higher in rank to have more bargaining power in choosing their livelihoods. Consequently, if one is higher in rank, the workload for them is less. The money earned through these three income-generating activities is then placed in a central pool and distributed and shared among members of the house based on the power structures within the hijra prestige economy system. Champa, a chela hijra says the following for a senior guru in the Laxmi Nagar area:

What is it that we have except our gurus? Our gurus are our saviors. They have rescued us from the harsh and brutal world. We have no one that we can trust, even our families, the one to which we were biologically born, have disowned us. Life is not perfect! In such a situation, even when we have to face some difficulties, it is only something that we have earned in return of our ill-doings and we deserve it. There is no other way of skipping it. It is all a part of life. (Champa, interview by author)

The maha nayaks, who are at the uppermost level in the hierarchy, do not have to go out and earn because they receive a portion of the earnings of those in the ranks below them. In exchange, they maintain social relations, order, and harmony within the hijra community by serving on the internal governing councils, known as panchayats or jamaats.

The hijra financial chain is a structure of systematic payments whereby those at the bottom of the structure pay those above them. Those higher in rank have a duty to care for their subordinates in the hijra prestige economy system. They also look after those who have been victims of sexual harassment, rape, and police violence. Those lower in rank often have multiple jobs. The nati-chelas may work as beggars in the morning and as sex workers in the evening; the chelas might works as ritual workers in the morning and sex workers in the evening. Irrespective of their workload, payments need to be given to their gurus. The gurus then pass a share from their collection to those higher up in rank and so on until it reaches the maha nayaks at the topmost tier.

Embodiment

Within the prestige economy system of the hijra community, those hijras who are castrated gain more respect than those who are not (see Reddy 2006). There is pressure on those lower in rank to be castrated, despite the fact that castration is not a prerequisite for becoming a hijra. Currently, there are both Nirwana (castrated) and Akwa (noncastrated) hijras in India. Pikoo, a castrated migrant hijra from Bangladesh at the Shashtri Park Theka area in New Delhi said:

This is a matter of confidence and trust alone. How can we give our lives to untrained and unprofessional hands with no experience at all? This is a question of life and death to us and we would rather go to our community’s trusted hands and healers who have been performing this ritual since generations. (Pikoo, interview by author)

This insistence of the religiosity of a castrated hijra body is rooted in three key factors. First, hijras are associated within Hindu mythology to many androgynous avatars of gods and goddesses (Pande 2004; Pattnaik 2015). In the Indian cultural context, hijras are accepted as androgynous avatars of those gods because of their socioreligious status in society. Acknowledging their age-old socioreligious approval, the hijras reappropriate their bargaining power within society by asking for voluntary donations in exchange for their blessings. In this process, there is an implicit understanding of an asexual and castrated hijra body. Kapila, another castrated migrant hijra from Bangladesh at the Shashtri Park Theka area in New Delhi said:

This is why we Hijras are considered to be god-like as we undergo such pain that ordinary men and women cannot even think of bearing. We are the closest to The Almighty and as folklore has it, in the Mahabharata, the greatest Indian epic of all times, we are called ‘Ardhanarishwar’, i.e. half-(wo)man half-god. (Kapila, interview by author)

Within a Hindu cosmological frame of reference, desire is seen as the root of all evil, and renouncing desire through asexuality and castration is seen as a way of being associated with rising above the material pleasures and becoming spiritual. Scholars argue that castration then does not embrace sexual ambiguity since the pressure is on renouncing it (Jaffrey 1996, 56). However, in the context of Muslim hijras, Hossain (2012, 498) argues that despite having Hindu practices, those hijras born Muslim can situate themselves into a Hindu cosmological frame of reference because Islam as a religion is open to this transcendence.

This spiritual status of the hijras is publicly acknowledged and accepted as part of their gender role, which entitles them to rise to the spiritual level of “others” who are nonhijras. Consequently, the hijras are elevated to the status of demigoddesses with spiritual abilities to confer fertility and good luck on those seeking their blessings. It is also considered a sin to refuse hijras money, as their curses are considered highly potent and dangerous. Most dangerous of all is the point in the negotiation when a hijra threatens to shame those who refuse to pay by lifting their skirts and exposing whatever lies beneath the hijra’s petticoat.

Second, the British colonialists criminalized hijras by banning them from public areas under the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA) of 1871. This act forced the hijra community underground as they were considered “eunuchs” responsible for sodomy, kidnapping, and castrating male children (see Hinchy 2019). Although the CTA was rescinded in 1952, a collective memory still paints hijras as historical gender deviants with a criminalized sexual variance. Testimony to this fact is that the first colonial antisodomy law introduced by the British in 1861 through Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) considered homosexuality an unnatural act and a public offense until 2018 in the postcolonial Indian nation-state. As a result of this colonial baggage, the mainstream society conflates hijras with homosexuals despite hijras being a gender identity and not a sexual identity.

Third, if not associated with castration, then the popular understanding of the hijra body is of those born with intersex variations. In fact, in colloquial Hindi, the term intersex is culturally synonymous with the term hijra. Within hijra communities, those born intersex are considered “natural” hijras who are “born that way.” There are also many Indian folktales about intersex children being donated by the birth parents to hijras who adopt those children with pride and increase the membership of their community. However, no person with an intersex variation can become a hijra without the patronage of a hijra guru.

Therefore, one of the crucial elements of rising in rank is achieving an ideal castrated hijra body—an element central to hijra performativity of gender. Consequently, often the hijra gurus pay for the castration of their chelas, in exchange for which the chelas pay the guru a portion of their income. This way the chelas also compensate their gurus financially for learning the hijra ways of gender performativity. However, the initial sum paid for castration is compounded with interest, and eventually the sum grows to a point where chelas are typically never actually able to repay this debt in full over a lifetime. As an outcome, kin relatedness within the hijra prestige economy system then also forms a kind of economic bond based on financial debt.

Some scholars have also viewed the guru-disciple lineage as a form of disguised “bonded labor,” especially if the hijra guru pays for the castration of their hijra disciple, in return for which the disciple is not only expected to remain in bonded servitude to their guru for a lifetime but also because there exists a hijra custom of “leti,” which is the amount payable by a hijra disciple to the guru if they leave their hijra guru for another (Saxena 2011, 159). The hijra disciple is also expected to repay the “loan” by turning in a share of their earnings and doing household chores in the hijra commune, which is “invariably greater than the original sum of money borrowed” from their hijra gurus (Mazumdar 2016, 46; see Goel 2019). Such internal rules also bound Sharmili to her hijra guru in Dakshinpuri who discriminated against her because of her lower-caste status, and Sharmili could not afford to pay the “leti” and take patronage under another guru in Trilokpuri.

Conclusion

Kinship has been a significant and essential area of study in anthropology, reflecting on the complicated and often contradictory nature of negotiating gender roles and sexuality. In the context of the hijras or “third” gender in India, androgynous nonbinary kinship becomes a critical site of examination for studying the hijra prestige economy system. Decisive aspects of maintaining hijra kin through performative aspects of respect, livelihoods, and embodiment are central to the hijra social system. Hijra kin relatedness is based on a system of informality not recognized by Indian law but, contradictorily and unknowingly, recognized in some aspect by the Indian government through issuing voter ID cards for hijras that carry the names of their gurus either as fathers or husbands. Therefore, hijra kinship functions as an androgynous institutionalized system of discipleship-lineage based on power relations and further legitimized by internal hijra councils.

Caste is an ever-evolving process of engagement between individual hijras within the hijra community, and the negotiation of the hijra caste identity is contingent upon several factors. Many aspects depend on the relationship hijras have with their gurus. As a collective unit, it is difficult to understand the intersection of caste with hijra kinship, and little is known about the intersection of the Indian caste hierarchies with the social stratification in the hijra community. Nonetheless, caste is an important, often hidden factor in determining kin relatedness within the hijra community, particularly through Sharmili’s narrative in the opening vignette of this chapter.

Hijra kinship, therefore, is a mutually coordinated support system maintained by a historically oppressed community by making it a hierarchically organized enclave that is mostly hidden from the outside world (Goel 2016). Through kinship, hijras sustain their ordered rankings within their cultural enclaves by justifying their logic according to the rules made by the internal governing councils of the hijra community, and this renders their community a “closed” social group.

Review Questions

- Why is kinship so important to the hijra community?

- How do Indian social hierarchies intersect with hijra kinship?

- How do power dynamics shape the relationship between hijra guru and chela?

Key Terms

caste system: Indian kinship is always grouped around a system of social stratification based on birth status known as the caste system.

Dalit: formerly “untouchable” community in India.

hijras: also known as “third” gender in India; can be understood as subaltern forms of trans-queer identities existing within a prestige economy system of kinship networks.

hijra gharanas: symbolic units of lineage guiding the overall schematic outlining of the social organization of hijra community in India.

hijra kinship: androgynous nonbinary family network, the continuation of which is based on a nonbiological discipleship-lineage system, which is based on power relations that are further legitimized by internal hijra councils.

hijra prestige economy system: a system of kin relatedness within the hijra community based on the social standing of hijras to one another.

joint-family: a household system in which members of more than one generation of a unilineal descent group live together.

kotis: effeminate men who are mostly gay or bisexual and are not affiliated to any hijra gharana.

Mughal: early modern empire in South Asia founded in 1526 that spanned two centuries.

nonbinary family network: kinship pattern for those who identify on the gender spectrum outside the male-female binary.

Resources for Further Exploration

- Butalia, Urvashi. 2011. Mona’s Story. GRANTA. https://granta.com/monas-story/

- Revathi, A. 2010. The Truth About Me: A Hijra Life Story. New Delhi: Penguin

- Interview with Indian activist Laxmi Narayan Tripathi on the third gender, Women in the World, 8 March 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mzhf29NBWbw.

- Goel, Ina. 2020. Impact of Covid-19 on Hijras, a Third-Gender Community in India, Covid-19, Fieldsights, May 4. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/impact-of-covid-19-on-hijras-a-third-gender-community-in-india.

Bibliography

Belkin, E. C. 2008. Creating Groups Outside the Caste System: The Devadasis and Hijras of India. Bachelor’s thesis, Wesleyan University.

Bhaskaran, Suparna. 2004. Made in India-Decolonizations, Queer Sexualities, Trans/national projects. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Butler, J. 2006. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” In The Routledge Falmer Reader in Gender & Education, 73–83. London: Routledge.

Census of India. 2011. https://www.census2011.co.in/transgender.php.

Chatterjee, I. 2002. “Alienation, Intimacy, and Gender: Problems for a History of Love in South Asia.” Queering India: Same-Sex Love and Eroticism in Indian Culture and Society, edited by Ruth Vanita, 61–76. New York: Routledge.

Datta, S. 2017. We Refuse to Be Subjects of Experiment for Those Who Do Not Understand Us: Transgender Persons Bill. Economic and Political Weekly 52, no. 49.

Dutta, A. 2012. An Epistemology of Collusion: Hijras, Kothis and the Historical (Dis) Continuity of Gender/Sexual Identities in Eastern India. Gender & History, 24, no. 3: 825–849.

Goel, I. 2016. Hijra Communities of Delhi. Sexualities 19, no. 5–6: 535–546.

———. 2018. Caste and Religion Create Barriers Within the Hijra Community. The Wire. 18 May. https://thewire.in/lgbtqia/caste-religion-hijra-community

———. 2019. Transing-normativities: Understanding Hijra Communes as Queer Homes in The Everyday Makings of Heteronormativity: Cross-cultural Explorations of Sex, Gender, and Sexuality, edited by Sertaç Sehlikoglu and Frank G. Karioris, 139–52. London: Lexington.

Hall, K. 2013.” Commentary I: ‘It’s a Hijra!’ Queer Linguistics Revisited.” Discourse & Society 24, no. 5: 634–642.

Hossain, A. 2012. “Beyond Emasculation: Being Muslim and Becoming Hijra in South Asia.”

Asian Studies Review 36, no. 4: 495–513.

Hinchy, J. 2015. “Enslaved Childhoods in Eighteenth-Century Awadh.” South Asian History and Culture 6, no. 3: 380–400.

Hinchy, Jessica. 2019. Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India: The Hijra, c. 1850–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jaffrey, Zia. 1996. The Invisibles: A Tale of the Eunuchs of India. New York: Pantheon.

Mazumdar, M. 2016. Hijra Lives: Negotiating Social Exclusion and Identities. Master’s thesis, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.

Nanda, Serena. 1990. Neither Man nor Woman: The Hijras of India. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth

Pande, Alka. 2004. Ardhanarishvara, the Androgyne: Probing the Gender Within. New Delhi: Rupa.

Pattanaik, Devdutt. 2015. Shikhandi and Others Tales They Don’t Tell You. New Delhi: Penguin.

Reddy, G. 2001. “Crossing ‘Lines’ of Subjectivity: The Negotiation of Sexual Identity in Hyderabad, India.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 24, no. 1: S91–S101.

———. 2006. With Respect to Sex: Negotiating Hijra Identity in South India. New Delhi: Yoda.

Salve, P., D. Bansod, and H. Kadlak. 2017. “Safai Karamcharis in a Vicious Cycle: A Study in the Perspective of Caste.” Economic & Political Weekly 52, no. 13: 38–41.

Saxena, Piyush. 2011. Life of a Eunuch. Mumbai: Shanta.

Taparia, S. 2011. Emasculated Bodies of Hijras: Sites of Imposed, Resisted and Negotiated Identities. Indian Journal of Gender Studies 18, no. 2: 167–184.

Weston, K. 1991. Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship. New York: Columbia University Press.

———. 1998. Long Slow Burn: Sexuality and Social Science. London: Routledge.

also known as “third” gender in India; can be understood as subaltern forms of trans-queer identities existing within a prestige economy system of kinship networks.

formerly “untouchable” community in India.

Indian kinship is always grouped around a system of social stratification based on birth status known as the caste system.

a household system in which members of more than one generation of a unilineal descent group live together.

symbolic units of lineage guiding the overall schematic outlining of the social organization of hijra community in India.

early modern empire in South Asia founded in 1526 that spanned two centuries.

androgynous nonbinary family network, the continuation of which is based on a nonbiological discipleship-lineage system, which is based on power relations that are further legitimized by internal hijra councils.

kinship pattern for those who identify on the gender spectrum outside the male-female binary.

a system of kin relatedness within the hijra community based on the social standing of hijras to one another.

effeminate men who are mostly gay or bisexual and are not affiliated to any hijra gharana.