Part V: The Global North (North America and Europe)

Susan W. Tratner

In this chapter, the author explores the competitive nature of the fishbowl culture in upper-middle-class communities in the northeastern United States and the ways that online forums mediate idealized parenting performances. The author addresses how these sites are used to help mothers with “impression management,” allowing women to practice their performances and improve the impressions they will provide for their real-life audiences in the future.

Learning Objectives

- Identify and analyze gender and parental social roles.

- Distinguish between backstage and front-stage behaviors and impression management using Goffman’s dramaturgical method.

- Interpret the rise of the Mommy Wars as a result of both technological change and unachieved feminist goals.

This chapter discusses research done with upper-middle-class cisgender heterosexual mothers in New York City who participate in the anonymous online discussion boards UrbanBaby.com (UB) and YouBeMom.com (YBM). In the age of “intensive parenting,” the social status of these mothers is inexorably tied to their parenting. Many in this social arena believe that if a mother is unwilling to give up (almost) everything in her previous life, then she should not have children. There are few who achieve this ideal, but many feel pressure to present this image to the world. This creates a tension between the social role of mother and the private reality of wanting to complain and have another identity. A social role is the expected behavior of a person who holds a known status. These boards are where female posters can drop the “perfect” façade and be their more “authentic” selves. These online spaces allow them to express insecurity when they should appear confident, to be rude when they are expected to be polite, and to be clueless when they are looked to for answers. In other words, these boards allow them to be more authentically human. On YBM and UB, it is possible to see some of the social tensions around the role of mother not changing as much as the role of a female employee. This leads to heated debates regarding parenting choices in paid employment versus maternal-only childcare that is part of the “Mommy Wars.”

Description of Boards

There are many websites with discussion boards devoted to the topics of pregnancy and childhood. Patricia Drentea and Jennifer Moren-Cross (2005) found these parenting boards to be places of both emotional and instrumental support that create and maintain social capital. The 2011 book Motherhood Online, edited by Michelle Moravec, discusses websites where mothers can get support regarding their personal lives. BabyCenter.com is currently the largest and most popular parenting site, serving over forty-five million users (babycenter.com/about). It has usernames and images that identify every post with a user. Those users are expected to be warm and supportive, giving virtual hugs “((((((HUGS))))))” when someone is having trouble.

UB and YBM do not provide this gender-specific comfort and loving support. They are believed to be populated by mean and nasty women. Even asking about how to change one’s eating patterns to more healthy ones can lead to a poster being told: “You sound fat.” John Suler coined the phrase “online disinhibition effect” for how people behave online in ways that might be hurtful to others, while they would not in real life (IRL). People act this way because of anonymity, invisibility (those being attacked cannot be seen), solipsistic introjection (lack of face-to-face cues), dissociative imagination (online is not “real life”), minimization of status and authority, individual differences, and predispositions and shifts among intrapsychic constellations (individuals showing a “true self” that they would typically hide) (Suler 2004). It happens to both genders but is more shocking to the viewer when the verbally abusive posters are female, never mind mothers.

Susan and John Maloney founded urbanbaby.com in August 1999. The site provided articles and information to expectant and new parents across the country. The most popular feature was the message board because it was an anonymous place for parents to speak without negative repercussions IRL. CNET bought the site in 2006 (Benkoil 2013) and is run by CBS. UB was ranked the 63,435th most popular website in global internet engagement in 2008 but fell to 314,048th in 2019 (Alexa.com 2019). This popularity came with notoriety as well. Jen Chung (2004) of Gawker.com said that it is a “must read if you’re about to have a kid in the five bouroughs [sic].” Journalist Emily Nussbaum (2006) called UB “the collective id” of some groups of New York City mothers and a “snake pit.” The site is famous not only for the snark but also as an anonymous and free resource on parenting in the New York area.

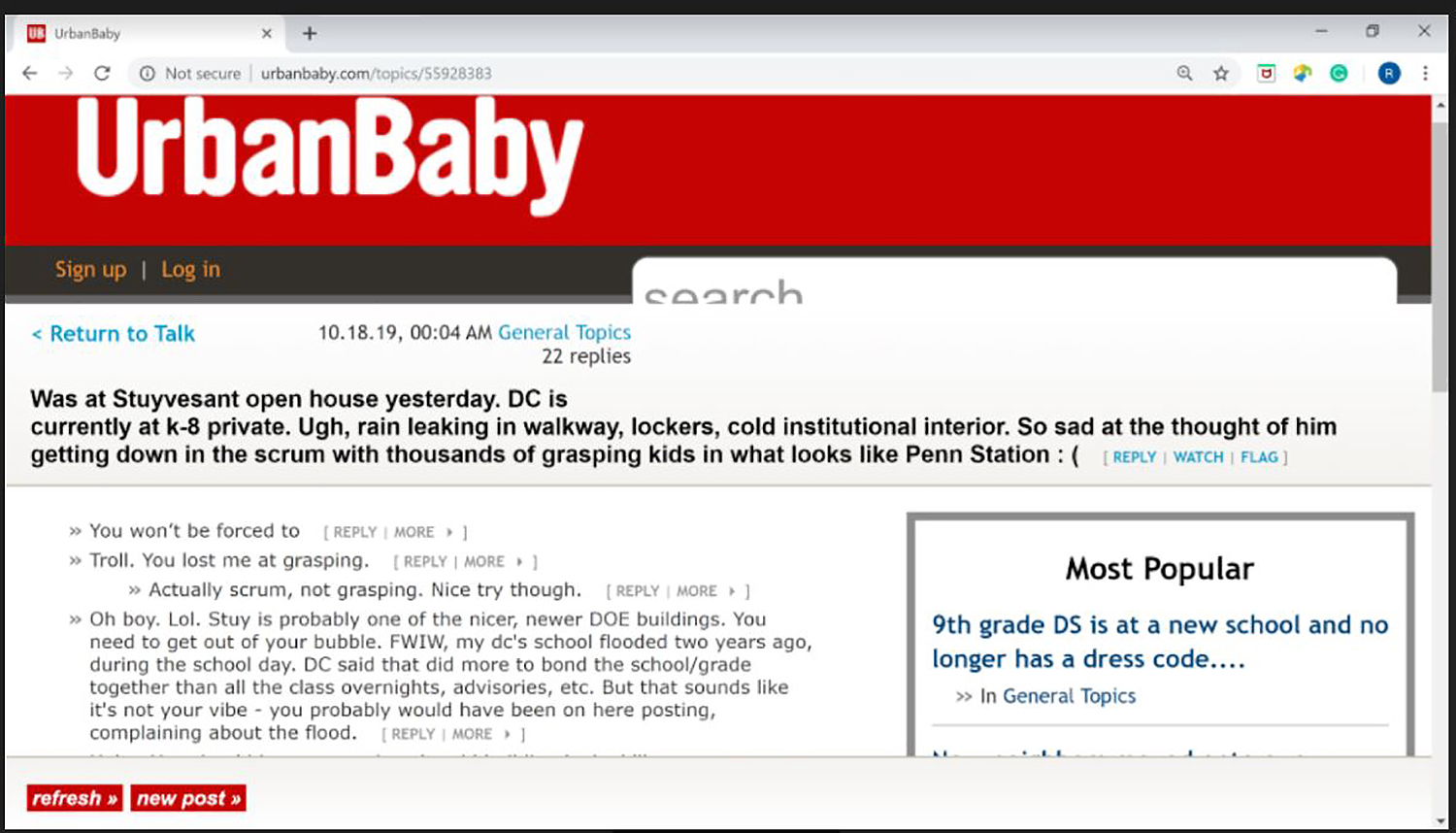

UB’s design is currently a relatively straightforward discussion board.

In 2008, UB changed its format to what you see in figure 16.1. Anyone can read the content, but commenting requires a username and password. The “Search Box” is not functional since a second reorganization in 2012. The “Most Popular” posts, listed on the right, are the ones that get the most responses. The gray links underneath the black posts allow a user to reply to a post, click on “watch” to create a personalized list, and “more” for the time stamp and ability to “flag” a post. Flagging is an effort to get CBS.com moderators to delete inappropriate (offensive or spam) posts.

The 2008 changes upset many longtime UB users, claiming the site was slower and less agile. Several New York–based news outlets reported users’ anger; in fact, the New York Times titled their article “Don’t Mess with Mom’s Chat” (Kaufman 2008). The negative fallout indicated how popular the site was in New York City and how UB members are politically and socially well connected. Mondeep Puri and an anonymous other former UB user founded a new website called YouBeMom.com. It has been called “the 4chan for mothers” (O’Conner 2014). The user demographic is similar and overlapping, and some move fluidly from one to the other, as verbatim questions appear within minutes of each other.

On YBM, only the first 180 characters are visible, and a user must click to see the remainder. It became possible to “delete” posts in mid-June 2017, a feature that posters have been using as a hedge against embarrassment. If three other users hit “dislike,” a comment will be “hidden” from view but not deleted. The “hide—like—dislike—reply” buttons are visible when a user clicks on a post. There is a “most liked” category and “most discussed” on the top navigation bar as well as a search box.

Geographic Setting—Virtual or New York City?

The research setting is a virtual community. It is a social network of people interacting using technology to pursue shared interests and goals that cross boundaries of geography, time, and politics (Rheingold 1993). The issue with saying UB and YBM are exclusively virtual communities is that it ignores the geographic grounding to the participants and their knowledge bases. These boards are used to communicate about parenting in a geographic location—the stores, schools, playgrounds, activities, etc.—that community members access regularly. Therefore, these virtual communities have a tie to the locations where their participants live. Posters are not looking for someone to tell them that they are insane to spend up to $50K a year for kindergarten. Instead, they want to know about the admissions process for a particular school. The geographic base of knowledge is small, and some people are only interested in getting recommendations close to their own homes.

“Who Are These Women?”

It is virtually impossible to know the exact demographics of the users of these sites because their personal data are not collected. In various articles about the users of these sites, community members are described as rich and mean women with too much time on their hands. Nolan (2012) says the site is “home to some of the most self-loathing, wealthy, haughty, and miserable parents in all of America.” I have a sense of demographics based on personal experience from 2009 to 2012 and official research between 2012 and 2019. YBM and UB populations skew heavily female, parents, geographically in the boroughs (counties) of Manhattan and gentrified Brooklyn with a significant subset of former Manhattanites and residents of the greater Tri-State Area commutable to New York City (meaning southern New York State, northern New Jersey, and much of Connecticut). They also are significantly wealthier than the median income (over $71,897 in 2018; see datausa.com) college-educated, Democratic political leanings, and white/Caucasian. There are indications of different lengths of tenure on each of the sites, longer on YBM and shorter on UB. One of my interviews was with a woman who said she was a former resident of Manhattan who moved to New Jersey, had two children, and stayed at home with them. She had initially gone to the site (as many informants reported) to find out about New York City’s competitive preschool application process. Although her children were in middle school by the time we talked, she enjoyed the ability to speak her mind and engage in “the drama” from the safety of her own home. In fact, she may enjoy it too much as she said she was “addicted” and had to ask her husband to block the website from their router most of the time in order to have a strict limit on her usage.

Motherhood and Impression Management

Most people can recognize that a job interview is a performance. Job seekers research the organization, get business attire ready in advance, prepare answers to potentially tricky questions, and ensure that they show their best selves at the interview. Parenting has increasingly become a performance as well. Since Sharon Hays reported the rise of “intensive parenting” in 1998, pregnancy, birth, childhood, and parenthood have become part of a carefully executed show requiring parental (read: maternal) supervision. Aspects of this have been true for centuries. The competitive nature of the culture in upscale parts of the northeastern United States shows how UB or YBM can become an invaluable lifeline. One of the primary reasons posters ask questions about UB and YBM is to poll others “like me.” They may ask, “What would you think if—” followed by a variety of parenting (or nonparenting) questions to shield themselves from judgment IRL. The anonymity allows people to give and get advice without harm to an individual’s reputation as a “good mother.”

The boards demonstrate the dramaturgical method, developed by Erving Goffman (1959) in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. He suggested that humans interact differently depending on the time, place, and audience present to view that “performance” or action. It indicates that people are actors playing (social) roles during their daily lives. The status that a person has is the part in the play, while the role is the script. The script informs the person of the appropriate words and movements for the part they are playing at this moment. Individuals can present themselves and create an impression in the minds of others (impression management) by changing status and role depending on social interaction. For example, most people present a different “self” to an in-law than to a spouse in terms of behaviors and expressions.

Goffman says that daily interactions in which people know there is an audience for his/her status and role are called front-stage behaviors. People are aware that they are performing in the front stage. There is a set of observers for whom a performance is being put on and a series of behaviors that social actors are expected to demonstrate. The performance has a goal of infallibility as “errors and mistakes are often corrected before the performance takes place, while telltale signs that errors have been made and corrected are themselves concealed” (Goffman 1978, 52). Those errors are discussed and fixed in backstage areas with compatriots who want to help you perfect your performance.

There are several signs to indicate that someone is in a backstage region or engaging in backstage behavior. First, they are among people for whom status does not depend on a positive review, or where one can “let down [their] hair.” Goffman quotes feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir who stated the following:

With other women, a woman is behind the scenes; she is polishing her equipment, but not in battle; she is getting her costume together, preparing her make-up, laying out her tactics; she is lingering in a dressing-gown and slippers in the wings before making her entrance on the stage; she likes this warm, easy, relaxed atmosphere… for some women this warm and frivolous intimacy is dearer than the serious pomp and relations with men. (Goffman 1959, 113, ellipses in original)

This sort of informality and willingness to challenge authority is what Goffman called “backstage language,” which might be taken as disrespectful for people and places considered ”front stage.” Posters on UB and YBM use atypical “female” language, including profanity or aggressive, opinionated speech patterns, further indicating that this is a backstage area.

Rebecca Tardy (2000) provided a Goffmanesque analysis of a playgroup of mothers in a college town. Tardy discusses the social pressure put on mothers to prove they are “good” moms. If they meet this standard, they should be able to protect their children from getting sick, which is impossible. She suggests that these mothers have two front stages. The first is in front of the “regular” world of mixed genders and representations of themselves as successful stay-at-home mothers. The next is the playgroup, which on the surface appears to be backstage because they can get information about being a mother, discuss their parenting issues, and talk about the messy biology of motherhood. However, Tardy found that in this backstage, the women were playing the role of a devoted mother. Tandy found that only in the activities associated with “Mom’s Night Out,” where the children were not present, could the women drop the role of mother and engage in less “good mom” impression management.

Drew Ross analyzed the benefits of using anonymous people as backstage resources to achieve goals. He researched an online community of people trying to pass a difficult test to become a London taxi driver. The average applicant spent two to four years studying over three hundred routes on twenty-five thousand streets as well as over twenty thousand landmarks within a six-mile radius of Charing Cross (TheKnowledgeTaxi). As studying for this test is an isolated and competitive situation, a website was created by test takers and those who have passed the test to assist others. People would post questions before or after they went out to learn one of the routes. Ross’s discussion of expertise pooling shows how these boards are learning networks based on active participation and communication between those who know and those who do not. Both future cabbies and these mothers need a space where more experienced learners mentor those less experienced ones by answering questions.

Feminism on Display

Gender and gender roles (see introduction) in the United States support the idea that women are viewed primarily as caregivers and that their contribution to the household is valued less than that of males. The idea of these discussion boards being a place for women to communicate about the problems and to assist each other, harkens back to First Wave feminism. Feminism is the idea that there should be economic, social, and political equality between people regardless of sex or gender. Feminist critique in anthropology was defined by Henrietta Moore (1988) as the analysis of gender and how gender is a structuring principle in society. Carol Hanisch (1969) stated that “the personal is political.” The “political” was not referring to elected office but a way to show that women do not have unique problems in society. Women who experience disrespect and discrimination have a set of challenges that can be addressed politically. First-wave feminism focused on earning the right to vote and other legal protections, while second-wave feminism looked at discrimination and equality with the slogan “the personal is political.” The idea behind this slogan is that if all housewives (typically white, middle-class, and heterosexual) discussed their personal issues they would become conscious of their common oppression. Third-wave feminism was to address the class and racial biases of the preceding two movements. In theory, YBM and UB could function as such consciousness-raising environments. There are elements of this where women get help in determining how to manage a tough workplace, “I just reached out to a former boss. Only been here a week and I hate it. How do I phrase it?” Yet when women admit to taking time to themselves, they are flamed (criticized) for maternal neglect. “My child just drew a picture of me sitting on my computer YBMing” resulted in a huge backlash. The pressures of the expectations of female behavior are demonstrated in the various ways that educated and wealthy women bicker and defend their choices. In theory, these backstage spaces should provide a greater awareness of the common problems of a single gender. Instead, there is anger and criticism. The division of women into warring factions rather than as a united whole has been a significant failing of the feminist movement. Nussbaum (2006) said, “If you read UrbanBaby, it’s hard not to be unsettled by the same conclusion that hit Friedan when she surveyed the mothers of America: that what seem like women’s private struggles can be seen as an expression of their shared experience.”

Mommy Wars

Mommy Wars refers to the idea that choices that women make in their roles as mothers line them up on opposing sides of a battlefield. It starts with the decisions around birth, to have an unmedicated childbirth, an epidural (a shot in the spine to stop the pain) or a cesarean section, continues with circumcising male babies or leaving them “intact,” to co-sleep or put a baby in a separate crib. Breastfeeding or formula feeding, letting a six-month-old baby “learn to sleep” by “crying it out” or if a child is rocked to sleep until he or she learns how to “go to sleep” is worthy of arguments with strangers. Daycare for socialization or a private nanny is not only a status signifier but can be seen as setting a child up for a lifetime of success or failure, depending on the individual’s opinion. One of the most hotly debated topics is that of a mother’s employment status. A woman’s different decision in this arena is taken as a personal affront on another woman’s choice. Here it is important to note that it is not a question of a woman working or not impacting women or the feminist movement as a whole. Instead, it is a questioning of the other woman’s individual choice as being “wrong” or “right” in a grander scheme.

Historically, two people would meet face to face and talk behind the back of the individual. They were engaging in “gossip” while criticizing another person known to them. It was considered a shameful thing for the other person to know that the busybodies had discussed him or her. With the internet, these conversations are not only more public, but also people are more ready to directly confront another person about the choices that they are making with their children. An example arose in October 2019 when a mother was talking about how “outrageous” she thought it was that her children expected her to provide regular childcare to her grandchildren, calling her daughter-in-law “entitled.” After being flamed (criticized) on one thread in YBM, she started another where she was told, “Don’t tell us. Tell them.” But that is a harder thing to do, particularly with criticism of another woman’s lifestyle.

The Mommy Wars are about a social system that pits women against each other rather than focusing on raising their children to be productive adults. As Steiner said, “Motherhood in America is fraught with defensiveness, infighting, ignorance, and judgment about what’s best for kids, family, and women—a true catfight among women” (2007, x). A 2013 Quester poll stated that 64 percent of mothers believed the Mommy Wars exist, but only 29 percent of them have experienced it. This statistic implies that the Mommy Wars are about stereotypes of different styles of mothering, rather than the reality of mothering. Women appear to only engage in the sort of competitive discussions or direct attacks in situations where the “other” is not personally known to them. It is difficult to criticize one’s sister-in-law to her face for her parenting choices. It is far easier to do it to a close friend one has little to no contact with by saying, “She’s so lazy. My brother works so hard, and she just sits at home.” But even more comfortable is to post comments on UB or YBM where no one can defend this friend (they can only support a stereotype of her). More importantly, no one can trace this criticism back to either her or you.

The Stay at Home/Work Out of the Home [SAH/WOH] debate is almost a daily “Most Discussed/Popular” on UB and YBM. Some posters go online to the boards to argue their side of an issue they have in real life, but others may be genuinely looking to understand the “opposing” points of view better. Many posters believe these choices indicate what sort of a mother you are—kind or cruel, selfish or selfless. The decision for a mother to stay at home with her child(ren) includes her desires, her spouse, as well as gender roles and economics. Many women on the boards suggest that their posttax salaries were not significantly higher than that of the nanny. According to Gold (2018), nannies earned $17.63 per hour for an average of fifty hours a week totaling just over $45,000 per annum. This is the take-home salary of a pediatric nurse (Ward 2017). While in college, women are not as strongly encouraged as men to think about the economic impact of their career choices. Also, they are encouraged implicitly or tacitly toward the more “feminine” careers of teaching, social work, or human resources. These are often believed to be more suited to a woman’s interests in relationships and interactions with people or a desire to help. They also pay significantly less than being a professor, psychologist, or accountant. Even if a husband and wife are both on career tracks to be corporate lawyers, the woman’s role as a “litigator” takes a back seat to that of “mother” and often not by choice. Johnston and Swanson’s 2006 research indicates that many mothers must plan their work around their duties as a mother.

Many of these culturally defined choices restrict how mothers can behave in the workplace, much more so than in the case of men. Men are fathers if they have a child, but women are only mothers if they meet specific social standards. Men are rarely judged negatively for their interactions with their children. If they provide financial support for their children, they are considered acceptable fathers, but the reverse is not always true for mothers. Women who work for a salary twelve hours a day may be derided on the boards as “auntie mommy,” implying that they are only partially in their children’s lives. Conversely, fathers can travel to another city for work from Monday through Friday and still be “good fathers” because they are “providing.”

The dynamic of the man earning more than the woman is expected. The economic provision to the family is believed to be biologically male work while child-rearing or home-making is female work. As Enobong Hanna Branch (2016) points out, these dichotomies are not as strong in the African American culture, which is a further indication that members of these boards are culturally Caucasian. In truth, there are no male or female childrearing tasks (other than breastfeeding); there are only tasks around the house and money that needs to be earned.

There is a sizable portion of the UB/YBM population who believe that women are uniquely and biologically destined to be caregivers. These posters not only talk about their own choices as being “natural” and “normal” but also denigrate those women who do not make the same ones. When asking a woman why she chose to go part time, she said “because I want to raise my own children.” This is coded language implying that those mothers who work are no longer the ones raising their kids. Instead, the “mother” role has been transferred to the (often) nonwhite and less educated nanny. This attitude is reflected in the core belief that women are born nurturers and the current cultural obsession of protecting children to the point at which they become “snowflakes.” To call a person a “snowflake” means that they are sheltered and coddled (or they might “melt” easily). To maintain protection of these precious children, a parent (read: mother) is necessary, as a paid help is often not as careful or nurturing.

One of the things that drives many women to quit good jobs and that many posters discuss is that they are expected to take care of the second shift. Hochschild and Machung’s (1989), ”second shift” refers to the time spent on household and childrearing tasks that mothers feel constitutes unacknowledged work. It is the time spent on these domestic chores that her social status of “mother” depends on. The second shift of work is unrecognized by the first paid job, as employers do not allow for flexibility regarding family demands on their employees. This means that as long as the idea of “caregiver” remained female, women feel this second shift as being their responsibility. When discussing a poster’s decision to move from a work-at-home job to work in an office, another said, “It’s not as easy as outsourcing and forgetting about it [childcare]. It’s still a lot of work to manage plus a commute and a full-time new job” (UB 2019, errors in original). This reflects a difference in expected “responsibility” for the children. This feeling of responsibility leads to a great deal of mental labor, which M. Blazoned (2014) labeled the “default parent.” This is a gender-neutral term for what most Americans would say is the “mom.” If a woman on YBM or UB tries to complain that her husband “has no idea when our son has to go to his therapies” or “out of town and husband didn’t send our daughter with a packed lunch for her trip. So the teacher called me” instead of receiving support for a common issue, she is often chastised. Typical responses might be, “Well, you married him” a reaction reflective of a patriarchal tone that continues to assign women the primary responsibility for family care, according to economist Nancy Folbre (2012). She suggests that one of the keys to an equal society is to define “family care as a challenging and important achievement for everyone rather than a sacred obligation for women alone.”

Women on UB and YBM have the education and means to reject that these stereotypical social roles of mothers are for women only, but they are deeply internalized. If these women accept the social norms of men as financially supporting the family, they are criticized by those on the opposite side, namely those who work. If a woman laments that she cannot afford to buy something, she is told: “Well then get a job.” The most virulent arguments happen when a divorce is on the horizon, and the SAH spouse is told that she has to support herself. The soon-to-be-divorced poster will argue that she and her husband made the decision together, so he should continue to support her and the children financially. The argument against her is that once she became “dependent on a man” that she was running the risk of this happening. One of the advantages of these boards is that your “backstage helpers” can provide clear and actionable advice before women are ready to tell people in real life. This can include the need to collect financial documents, set up a separate bank account, and obtain the names of good local divorce attorneys.

These rigid roles are reflected in discussions of an SAH dad or those husbands who are unemployed. Some posters say that the family decided that the mother’s career was more lucrative, so the father stayed home. This works for them, but their posts are often tinged with defensiveness and guilt, likely representing their experiences going against the cultural norm. The husbands who are out of work often claim that the nanny needs to continue her work because he cannot both care for the children and look for a new job. The reverse is not true because SAH mothers report that they are able to get interviews and are hired before they get a nanny to replace their household labor. The SAH fathers who achieve the female ideal are still not given the same respect expected by the SAH mothers. They are described as “beta” men, meaning that they were SAH because they were not strong enough to dominate with the alphas in the workplace.

Discussion

While YBM and UB can help mothers present better offline impressions, they can also be harsh and accusatory, criticizing these women’s perceived internalized lack of respect for their roles in a family, employment, and society as a whole. As such, the Mommy Wars and the conversations around them provide a critical window into American feminism that has not yet been addressed. Online disinhibition explains the angry backstage behaviors but not the particular virulence that arises when discussing topics that surround the Mommy Wars. Based on the participant observation research, it is possibly due to three potentially interrelated reasons. First, the required changes in social roles have not occurred. Although girls have been taught that they “can be anything,” this related only to the workplace. If they choose to be mothers, that social status of all-encompassing love and protector of children with a father as a provider has not changed. Second is the internet. Online disinhibition and the increased contact through discussion boards (such as UB and YBM), social media (Facebook and Instagram), and the proliferation of online information sources have brought people the means of expressing opinions to people with different points of view. Parents (indeed everyone) can find an echo chamber that reinforces their particular worldview, which leads to hardened opinions and stronger adverse reactions to “the other.” Third, there remains a good deal of internal misogyny that is revealed in these anonymous backstage spaces. Women attack each other’s choices, not only to bolster their own decisions but because there is seemingly no choice a woman can make that is the correct one. Both working outside the home and staying at home with children are “wrong” choices that either hurt the family, the children, or all women. Conversely, fathers can get social support for working hard or finding work/life balance, and they only experience social backlash if they engage in the female task of SAH parenting. This is the paradox of so-called choice feminism being accepted before basic respect for women was achieved. Instead of every choice being a feminist one to be celebrated, none of the options are respected.

Review Questions

- What social roles do you play in a typical day?

- What is your “backstage” and who helps you with your “impression management”?

- What was your thought process in deciding on your major (or prospective major)? Did gender play a role? Did future career earnings? Why or why not?

- Why have gender roles in the workplace changed more readily than those of mother and father?

- The author puts forth several possible reasons for the Mommy Wars. Which is most convincing to you? Why?

Resources for Further Exploration

- Ammari, T., S. Schoenebeck, and D. M. Romero. 2018. “Pseudonymous Parents: Comparing Parenting Roles and Identities on the Mommit and Daddit subreddits.” In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (April): 1–13.

- Collett, J. L. 2005. “What Kind of Mother am I? Impression Management and the Social Construction of Motherhood. Symbolic Interaction 28, no. 3: 327–347.

- Marshall, Debra. “Erving Goffman’s Dramaturgy.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VpTSG6YtaeY.

- Scarborough, W. J., R. Sin, and B. Risman. 2019. “Attitudes and the Stalled Gender Revolution: Egalitarianism, Traditionalism, and Ambivalence from 1977 through 2016.” Gender & Society 33, no. 2: 173–200.

Key Terms

backstage: a social or physical space where people get help putting together a performance. Others help them perfect their portrayal of a particular role that they will demonstrate at another time or place.

feminism: the idea that there should be economic, social, and political equality between people regardless of sex or gender.

first-wave feminism: from the late nineteenth through the early twentieth century, focusing on earning the right to vote and emancipation of women from fathers and husbands.

front stage: a social or physical space where people are aware that they are performing a role for observers and a series of behaviors that social actors are expected to demonstrate.

gender: the set of culturally and historically invented beliefs and expectations about gender that one learns and performs (e.g., masculine, feminine). Gender is an “identity” one can choose in some societies, but there is pressure in all societies to conform to expected gender roles and identities.

gender roles: the tasks and activities that a specific culture assigns to a gender.

impression management: the manner in which individuals present themselves and create a perception in the mind of others by changing status and roles depending on social interaction.

Mommy Wars: the idea that choices that women make in their roles as mothers line them up on opposing sides of a battlefield.

participant observation: A research methodology used in cultural anthropology. It consists of a type of observation in which the anthropologist observes while participating in the same activities in which her informants are engaged.

second-wave feminism: focused on gender-based discrimination in the 1960s–1980s

second shift: the time parents spent on household and child-rearing tasks after the paid work has ended.

social role: the expected behaviors of a person who holds a known status.

third-wave feminism: brought up the idea that feminism and gender-based needs and oppressions differ based on class, race/ethnicity, nationality, and religion.

virtual community: a social network of people interacting using technology to pursue shared interests and goals that cross boundaries of geography, time, and politics.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the academic support of Roger Sanjek, Julie Gedro, Cynthia Ward, and Ruth Goldberg and the personal support of my parents (Alan and Irene Warshauer), my husband (Matthew Tratner), children (Ian and Miles) as well as friends and family. I would like to dedicate this work to my mother, a trailblazing woman in the legal profession who found her own way as a wife and mother, and my father, a feminist in word and deed.

Bibliography

Alexa. http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/urbanbaby.com. Accessed August 6, 2019.

Babycenter. https://www.babycenter.com/about. Accessed August 6, 2019.

Barriteau, Eudene, ed. 2003. Confronting Power, Theorizing Gender: Interdisciplinary Perspectives in the Caribbean. Kingston: University of West Indies Press..

Becker, Mary E. 1986. “Barriers Facing Women in the Wage-Labor Market and the Need for Additional Remedies: A Reply to Fischel and Lazear.” University of Chicago Law Review 53: 934.

Beneria, Lourdes. 1981. “Conceptualizing the Labor Force: The Underestimation of Women’s Economic Activities.” Journal of Development Studies 17, no. 3: 10–28.

Benkoil, Dorian. 2013. “Tumblr CEO David Karp’s Wild Ride from 14-Year-Old Intern to Multimillionaire.” Mediashift (website), http://mediashift.org/2013/05/tumblr-ceo-david-karps-wild-ride-from-14-year-old-intern-to-multimillionaire/. Accessed August 6, 2019.

Blazoned, M. 2014. “The Default Parent.” The Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-default-parent_b_6031128. Accessed August 6, 2019.

Branch, Enobong Hanna. 2016.”Racializing Family Ideals: Breadwinning, Domesticity and the Negotiation of Insecurity.” In Beyond the Cubicle: Job Insecurity, Intimacy, and the Flexible Self, edited by J. Allison Pugh. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Brown, Tamara Mose. Raising Brooklyn: Nannies, Childcare, and Caribbeans Creating Community. New York: New York University Press.

Chung, Jen. 2004. “NYC to Parents: Watch Your Baby!” Gothamist (website). https://gothamist.com/2004/08/30/nyc_to_parents_watch_your_baby.php. Accessed August 6, 2019.

Coleman, Gabriella. 2014. Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous. New York: Verso.

Coleman, E. Gabriella. 2012. “Am I Anonymous?” Limn 1, no. 2. https://limn.it/articles/am-i-anonymous/. Accessed August 9, 2019.

Datausa. 2019. New York Profile. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/new-york-northern-new-jersey-long-island-ny-nj-pa-metro-area. Accessed August 9, 2019.

De Beauvoir, Simone. 2012. The Second Sex. New York: Vintage.

Drentea, Patricia, and Jennifer L. Moren‐Cross. 2005. “Social Capital and Social Support on the Web: The Case of an Internet Mother Site.” Sociology of Health & Illness 27, no. 7: 920–943.

Folbre, Nancy. 2012. “Patriarchal Norms Still Shape Family Care.” New York Times Economix (blog). http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/17/women-should-take-care-of-home-and-family/?_r=0. Accessed August 9, 2019.

Gold, Tammy. 2018. “What Is the Average Nanny Salary in NYC: Survey Results.” The Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/what-is-the-average-nanny-salary-in-nyc-survey-results_b_5a561ed8e4b0baa6abf162e4. Accessed August 9, 2019.

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Harmondsworth.

Crow, Barbara A., ed. 2000. Radical Feminism: A Documentary Reader. New York: New York University Press.

Hays, Sharon. 1998. The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hochschild, Arlie, and Anne Machung. The Second Shift: Working Families and the Revolution at Home. New York: Penguin, 2012.

Johnston, Deirdre D., and Debra H. Swanson. 2006. “Constructing the ‘Good Mother’: The Experience of Mothering Ideologies by Work Status.” Sex Roles 54, no. 7–8: 509–519.

Kaufmann, Joanne. 2008. “Urban Baby’s Lesson: Don’t Mess with Mom’s Chat.” New York Times, May 19, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/19/business/19baby.html.

Knowledge Taxi. https://www.theknowledgetaxi.co.uk/. Accessed August 7, 2019.

Moore, Henrietta L. 1988. Feminism and Anthropology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Moravec, Michelle, ed. 2011. Motherhood Online. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars.

Nolan, Hamilton. 2012. “Rich Person or Troll? The Perpetual UrbanBaby Riddle.” Gawker (website). https://gawker.com/5889700/rich-person-or-troll-the-perpetual-urbanbaby-riddle. Accessed July 15, 2019.

Nussbaum, Emily. 2006. “Mothers Anonymous.” New York Magazine. http://nymag.com/news/features/17668/. Accessed August 7, 2019.

New York County. Information. https://www.ny.gov/counties/new-york#.

O’Conner, Brendan. 2014. “YouBeMom: The Anything-Goes Parenting Cult That’s Basically 4chan for Mothers.” https://www.dailydot.com/unclick/youbemom-4chan-for-moms/. Accessed August 7, 2019.

Pinch, Trevor. 2010. “The Invisible Technologies of Goffman’s Sociology from the Merry-Go-Round to the Internet.” Technology and Culture 51, no. 2: 409–424.

Portes, Alejandro. 1998. “Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 24: 1–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/223472. Accessed August 7, 2019.

Reference for Business. 2019. iVillage Inc. Company Profile. https://www.referenceforbusiness.com/history2/69/iVillage-Inc.html. Accessed August 6, 2019.

Quester. “Do Mommy Wars Exist?” August 29, 2013. https://www.quester.com/do-mommy-wars-exist/.

QuickFacts, New York City. https://archive.org/details/perma_cc_D6K2-CW2B. Accessed May 19, 2014.

Rheingold, Howard. 2000. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rosaldo, Michelle Z. 1980. “The Use and Abuse of Anthropology: Reflections on Feminism and Cross-cultural Understanding.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 5.3: 389–417.

Sannicolas, Nikki. 1997. “Erving Goffman, Dramaturgy, and Online Relationships.” Cibersociology. https://www.cybersociology.com/files/1_2_sannicolas.html. Accessed July 16, 2021

Schoenebeck, Sarita Yardi. 2013. “The Secret Life of Online Moms: Anonymity and Disinhibition on YouBeMom.com.” Seventh International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

Steinberg, Ronnie J. 1990. “Social Construction of Skill: Gender, Power, and Comparable Worth.” Work and Occupations 17, no. 4: 449–82. doi:10.1177/0730888490017004004.

Steiner, Leslie Morgan. 2007. Mommy Wars: Stay-at-Home and Career Moms Face Off on Their Choices, Their Lives, Their Families. New York: Random House.

Suler, John. 2004. “The Online Disinhibition Effect.” Cyberpsychology & Behavior 7, no. 3: 321–326.

Tardy, Rebecca W. 2000. “‘But I Am a Good Mom’: The Social Construction of Motherhood through Health-Care Conversations.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 29, no. 4: 433–473.

Urbanbaby. http://www.urbanbaby.com/topics/55921444. Accessed August 7, 2019.

US Census Quick Facts, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/newyorkcitynewyork,NY/RHI425216#viewtop. Accessed August 6, 2019.

Ward, Marguerite. 2017. “In Demand Entry Level Jobs Every College Student Should Consider.” CNBC.com. https://www.cnbc.com/2017/04/26/5-in-demand-entry-level-jobs-every-college-student-should-consider.html. Accessed August 9, 2019.

the expected behaviors of a person who holds a known status.

a social network of people interacting using technology to pursue shared interests and goals that cross boundaries of geography, time, and politics.

the manner in which individuals present themselves and create a perception in the mind of others by changing status and roles depending on social interaction.

a social or physical space where people are aware that they are performing a role for observers and a series of behaviors that social actors are expected to demonstrate.

a social or physical space where people get help putting together a performance. Others help them perfect their portrayal of a particular role that they will demonstrate at another time or place.

the set of culturally and historically invented beliefs and expectations about gender that one learns and performs (e.g., masculine, feminine). Gender is an “identity” one can choose in some societies, but there is pressure in all societies to conform to expected gender roles and identities.

the tasks and activities that a specific culture assigns to a gender.

the idea that there should be economic, social, and political equality between people regardless of sex or gender.

from the late nineteenth through the early twentieth century, focusing on earning the right to vote and emancipation of women from fathers and husbands.

1960s–1980s addressed issues of equal legal and social rights for women. Its emblematic slogan was “the personal is political.”

began in the 1990s responding to the shortcomings of the Second Wave, namely that it focused on the experiences of upper-middle-class white women. Third Wave feminism is rooted in the idea of women’s lives as intersectional, highlighting how race, ethnicity, class, religion, gender, and nationality are all significant factors when discussing feminism.

the idea that choices that women make in their roles as mothers line them up on opposing sides of a battlefield.

the time parents spent on household and child-rearing tasks after the paid work has ended.

A research methodology used in cultural anthropology. It consists of a type of observation in which the anthropologist observes while participating in the same activities in which her informants are engaged.